"I like skin," Lucian Freud is on record as saying. "It's so unpredictable." To anyone with a passing knowledge of the artist often called the greatest British painter of his lifetime, this will come as no shock. He is best-known for his huge, full-body, naked portraits, often of subjects with ample proportions, such as Benefits Supervisor Sleeping, which was sold in 2008 for US$33.6 million (Dh123m), a record for a living painter (Freud died last July).

Its sitter, Sue Tilley, who still works at a jobcentre in London, attended a private viewing just before the official opening last week of Lucian Freud Portraits, on at the National Portrait Gallery in the UK capital until May 27, alongside the Duchess of Cambridge, Bella and Esther Freud, and assorted members of the art world aristocracy.

They were among the first to see Freud's last painting, Portrait of the Hound, which was on public display for the first time, and shows Freud's longtime studio assistant David Dawson, naked and viewed from above, with Dawson's whippet Eli. It has the same ineffable combination of steeliness, pathos and palpable interest in flesh that makes Freud's mature work so remarkable.

Elsewhere, a room is devoted to several portraits of Tilley, sprawled naked on a sofa, an armchair, and, in one uncomfortable-looking picture, the floor. Nothing is idealised in any of these portraits: flesh bulges, skin is mottled, noses are bulbous, rashes and sores are lingered over; but a luminosity in the thick, built-up dashes of paint and a tenderness at the human form so vulnerably displayed makes the overall effect majestic.

Posing for a bank of photographers at a press view in front of the portraits, Tilley looked glamorous in a floor-length dress, and told reporters that she loved the paintings of herself and relished the memory of her time with Freud. The prospect of a future queen, who has an art history degree, seeing her pictured nude did not faze her.

"It's art, you know," she said. "Poor woman, I'm sure she's seen things before."

Michael Auping, the chief curator at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, where the exhibition will travel in July, was looking forward to seeing the works in Texas because "we have nothing like this in America. We are the land of Photoshop. We are the land of sleek models. We are the land of no wrinkles". By contrast, he went on to describe American art as one of "flatness and distance", citing Edward Hopper and Grant Wood.

The most striking works on show are the larger-than-life nudes, including a series on the wild performance artist Leigh Bowery, whose confrontational stare is at odds with all his soft, exposed flesh, but they are not the only pleasures in this comprehensive exhibition, which encompasses more than 130 pieces. Portraits of Freud's daughters, of David Hockney and of Andrew Parker-Bowles (who looks uncomfortable in an ill-fitting brigadier's uniform) give an insight into Freud's inner circle, and show his uncanny ability to get under the skin of subjects, even when they are clothed.

Others of some of Freud's most famous sitters, including Queen Elizabeth and Kate Moss, are not included, but there are photographs of both of them sitting for him - or in Moss's case, cuddling up to the artist in a bed. (The picture looks more platonic than romantic, although Freud took young lovers right up until his last years.) Viewers familiar with Freud's grandfather Sigmund may be interested, though, to see a series of paintings of the artist's mother. As Auping puts it: "Keep an eye on those pictures." He explained that Lucian told him that he distanced himself from his mother in his early years, but later in her life, he invited her to sit for him, "which was a way of him being able to, I suppose, be with her without having to talk to her".

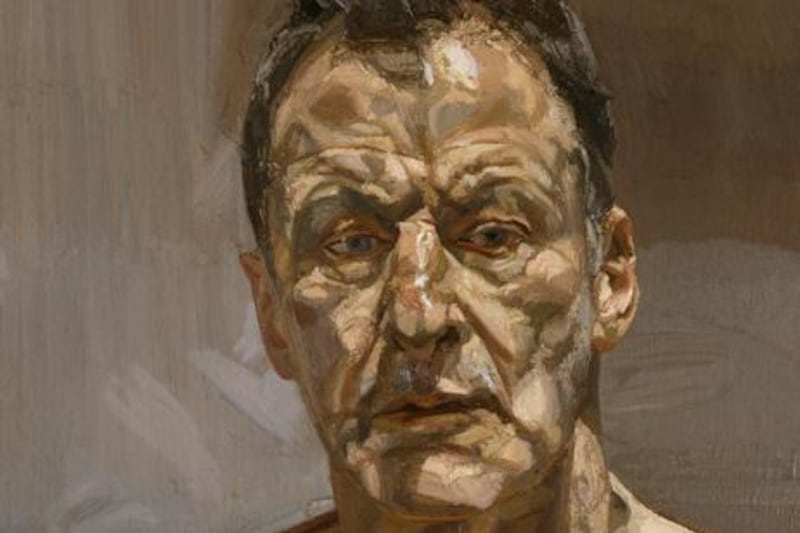

There is also a series of early works - the first, a portrait of Freud's art-school teacher, painted at the age of 18 - that are unrecognisable as his. As two-dimensional as any Wood or Hopper, they are delicate oils painted with a fine sable brush. The show is arranged roughly chronologically, and to see the development from these images, painted with the artist sitting knee-to-knee with his subjects, to those he made standing up, with thick hog's-hair brushes, on to his first nude and then to his first full-body nude, is to see an artist finding his own best form of expression, which he honed over seven decades of work.

"When he got up out of the chair and stood up, and his brush stroke started to be more active and broad," Auping said, Freud "got much more interested in skin." He said that he had frequently asked the painter why he did so many nudes, "and he would say every time, 'it's the most complete portrait'".

Lucian Freud Portraits is on at the National Portrait Gallery in London until May 27

Follow us on Twitter and keep up to date with the latest in arts and lifestyle news at twitter.com/LifeNationalUAE