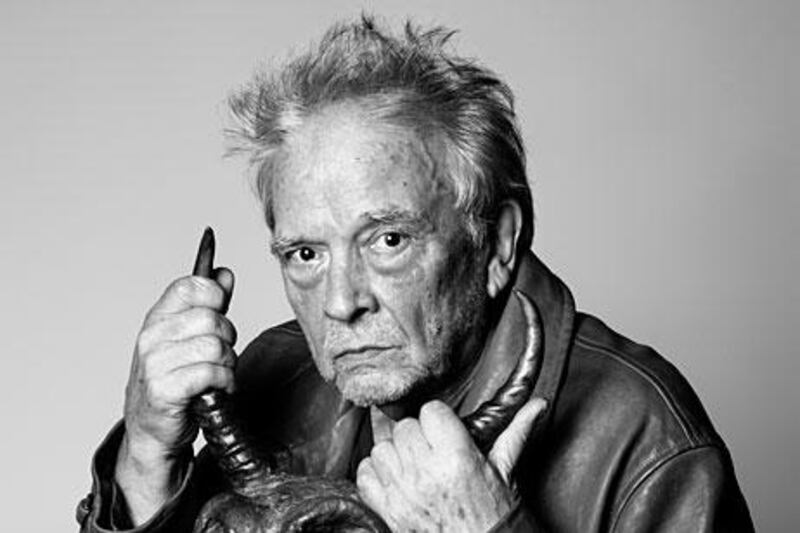

London's Pangolin Gallery played host to a surprising new exhibition this autumn when David Bailey, the photographer made famous by his iconic images of the Swinging Sixties, showed his sculptures for the first time. The series of bronze casts and prints of skulls and masks look past the superficial and delve into our very being. "You should look into somebody's face, and be able to see their history," Bailey says of his subjects and in his sculpture he went a step further by looking deep inside the face at the skull that underlies it.

With admirers as diverse as Damien Hirst and Sheikh Saud Al Thani, Bailey remains at the forefront of the international arts scene. "He's a friend of mine," says Bailey of the Qatari collector. "He's got quite a lot of my stuff. He's got tremendous taste." He chuckles with characteristic vigour before pausing. "But photography's just a snippet on the side of his collection. The things he buys are truly wonderful."

Bailey's work has made its way to the UAE through the legendary art dealer Larry Gagosian, whose current show at Manarat al Saadiyat, the exhibition space on Abu Dhabi's Saadiyat Island, has brought some of Bailey's 1960s contemporaries to the Emirates. "The things I sell in the UAE are always through Gagosian," he says. "I appreciate the way Arabs think and the way they believe in destiny. Abu Dhabi is one of the few places in the world that nurtures new young artists."

Bailey knows a thing or two about capturing interest. The saying goes that if you can remember the 1960s you weren't really there, so a great many people owe the photographer a debt of gratitude because he recorded the decade for posterity. After joining Vogue in 1960, the East End of London school rebel was soon shooting the good the bad and the ugly of the capital, taking iconic images of the model Jean Shrimpton, the Rolling Stones, and the gangsters Ronnie and Reggie Kray.

His sculptures were cast in bronze by Pangolin's founders, whom he met at the house of fellow skull-enthusiast Hirst. "The skull is nature's sculpture," explains Bailey in his London studio. "The old ones get this lovely patina, like a bronze." He has amassed a collection of crania old and new, from gorillas and giraffes to tigers, and large prints of some of these skulls were included in the exhibition.

"Sculpture's like photography," says Bailey. "It's just a way of trying to see, trying to interpret the world." His multidisciplinary approach to art colours his reaction to labels such as "fine art photographer". "Those are some of the most embarrassing words I ever hear," he says. "Everyone nowadays ends up taking the same picture: a 19-year-old girl looking idiotic in a tattered frock, surrounded by the sort of peeling wallpaper that you'd never dream of living with, and a TV on in the background with news coverage of bombs blowing up. That's fine art photography? I don't get it. I much prefer something honest.

"I'm a maker of images," he continues. "As long as it's visual I don't mind doing it. I've done lots of paintings, documentaries, features and directed more than a thousand commercials."

But why is the godfather of the celebrity portrait - now such an inherent part of our culture - moving into Picasso-esque primitivism using found objects and motifs from African and Pacific masks? Is this a deliberate move into more conventionally artistic, cerebral (or at least cranial) media? "I don't understand this division between commercial and non-commercial," he says. "There's no one more commercial than Raphael - he worked for St Peters, which was effectively the biggest advertising agency in the world at the time. They certainly had spectacular headquarters.

"Only a couple of nuts like Van Gogh and Gauguin weren't in it for the money. Art for art's sake is a myth. That said, I don't think you can be [only] in it for the money. I don't do what I do for money. But that doesn't mean I want to cut my ear off and live in Epping Forest."

And why the fascination with the skulls? Fighting his own mortality? Reminding the viewer of theirs? Bailey laughs.

"You are getting older, I can guarantee that. And you are going to die one day. But that's not why I do it. It's just something I do." He recounts the story of the philosopher Hegel on his deathbed, who reportedly said: "Nobody ever really understood me. Except one man. And even he didn't really understand."

He counts Picasso - "a genius, he changed everything" - as a major influence, particularly on his use of tribal imagery, such as the totem-like Goat's Head or the talismanic Claude, which combines a rough-hewn human head with the lower jaw of a crocodile. The pieces fuse philosophical reflection on mortality and nature with a mordant humour evident in Comfortable Skull, which shows a cranium resting peacefully on a chair. The skull may be comfortable, but the viewer is not.

Dead Andy, the sculpture that most ties Bailey to his roots in both celebrity iconography and the 1960s, is the piece that kicked off this late burst of sculptures. Out of one of the mass-market food tins that became pop-art icons, an explosion of beans forms a crude skull topped by the unmistakeable hair of Andy Warhol, whose belief in fame and the ephemeral was born in the 1960s and, ironically, is still very much with us. Does Bailey see himself as part of the movement defined by Warhol? "No. I knew Andy very well, but what's behind those images of Marilyn? People like it because it's Marilyn Monroe, or Liz Taylor, or Jackie Kennedy. They don't go for the Electric Chair, which is probably the best thing he ever did."

The public's preference for pretty pictures of actresses or gritty rock-stars has affected Bailey's own critical reception. "I always get the same thing - 'Can you do us a black-and-white picture of John Lennon in the sixties?' Michelangelo must have been sick of it - 'Can you do us another ceiling, like that one you did down the road?'" Bailey stops and grins: "I know what you journalists are like, and in no way am I comparing myself with Michelangelo."

Despite his protestation, Bailey doesn't seem too bothered about the press or public reaction to his sculptures - whether people read into them the metaphors he may have intended, or enjoyed their visual wit, or dismissed them as the productions of an ageing dilettante. "It's just something I do. Always have done - some of these pieces are almost 20 years old. I don't really care if the public like it or not."

Bailey's exhibition demonstrated that the image, not the medium, is the key thing. "I don't know what art is because I'm not even sure I know what the word art means. It's a bit like love. It's so subjective. The image is the important thing. That's the message. And if in that message there's something hidden, then that's OK. But you have got to start with something that people want to look at. Otherwise they'll never notice it."