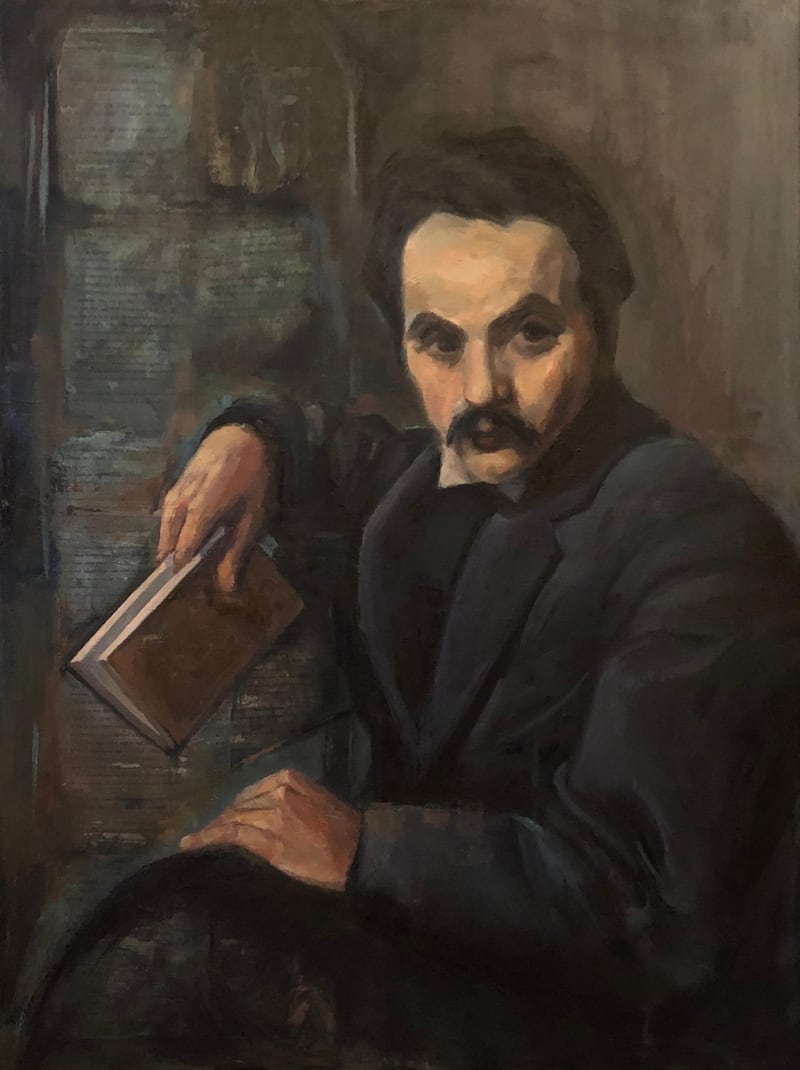

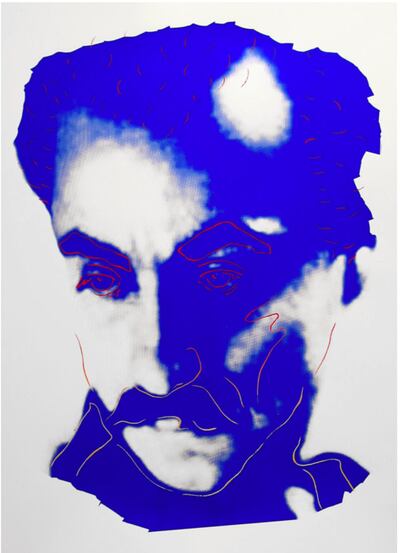

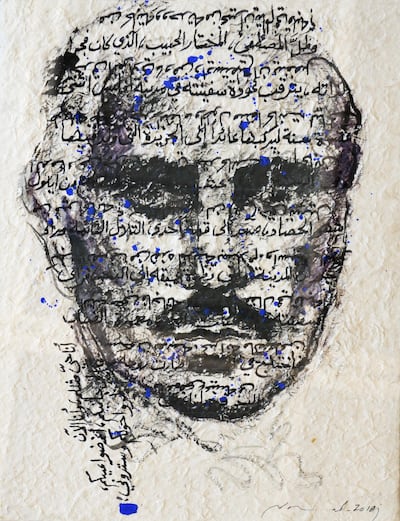

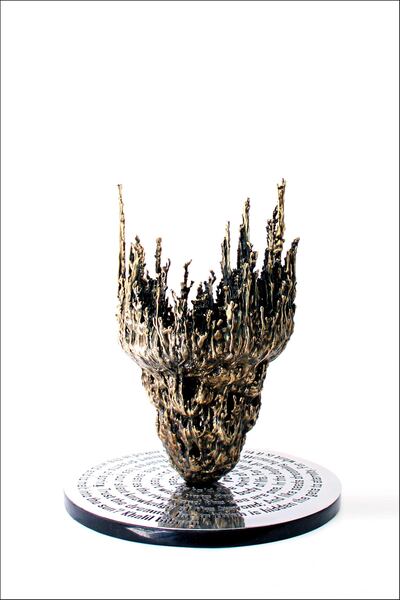

The works embedded throughout this article all draw directly from Kahlil Gibran's works and are from the exhibition A Guide for Our Times...

This week and next sees separate events in London celebrating the life and work of one of Lebanon's most famous sons, Kahlil Gibran, an artist and author whose enduring reputation rests on his most famous work, The Prophet. The book of lyrical spiritual guidance has earned Gibran a global following since it was first published in 1923.

Ninety-five years later, Gibran's influence continues to hold sway: last Wednesday, a new theatrical musical received its premiere at London's Theatre Royal Haymarket. Set against the backdrop of early 20th-century New York and Beirut, The Broken Wings is a tragic tale of migration, dislocation and thwarted love, with the plot based on a poetic 1912 novel of the same name, which was written in Arabic before Gibran achieved international recognition.

An exhibition, Kahlil Gibran: A Guide for Our Times, also opens at Sotheby’s Mayfair galleries next Monday, and features works by 38 artists, each of whom have responded in some way to Gibran’s work.

Following earlier shows in Cairo and Bahrain, the exhibition is co-curated in partnership with the Arab British Centre by Marion Fromlet Baecker and Janet Rady, a Middle East art expert and former head of development for Art Bahrain who also runs galleries in London and Dubai.

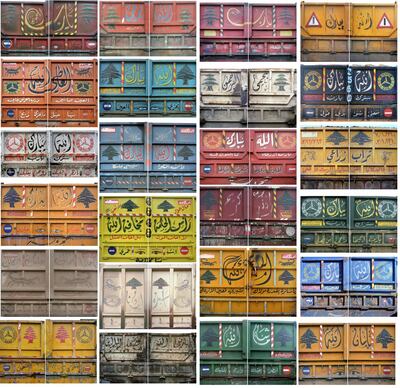

The exhibits range from reinterpretations of portraits of the famously photogenic Gibran, to depictions of his characters, or more tangentially to his wider spiritual message of love, peace and understanding. While drawings such as Sarah Aradi's Young Sage fall into the first category, Mahrooseh, a photomontage by Camille Zakharia – a celebrated Lebanese artist living in Bahrain – definitely belongs to the latter. Set in a six-by-four grid, Mahrooseh features 24 photographs of the blessings, prayers, lyrics and proverbs traditionally painted on trucks in Lebanon, a kind of cross-cultural folk art that unites drivers of all creeds in their quest for safe passage, regardless of their religion.

In a statement accompanying the work Zakharia, whose work has also been shortlisted for the prestigious Jameel Prize and included in the Bahrain pavilion at the 2010 Venice International Architecture Exhibition, references a quote from The Prophet:

“I love you when you bow in your mosque, kneel in your temple, pray in your church. For you and I are sons of one religion, and it is the spirit.”

“The writing on the backs of the trucks are often wishes praying for their safe return after a long trip, or protection of the large vehicle from accidents,” Zakharia writes. “Drivers of these trucks belong to different religious backgrounds: Muslim and Christian. They both unite in their prayers seeking God’s mercy.”

The sentiment of the work and the quote chimes perfectly with both the theme of the exhibition and with the mission of its organiser, Caravan, a charity dedicated to using the arts for peace-building and to engage with different faith groups both within the Middle East and beyond.

The charity is the brainchild of Paul-Gordon Chandler, an American Episcopalian priest and inter-faith advocate who has spent many years working for the church, NGOs and development agencies in Europe and North Africa. It was established in 2009 while Chandler was serving as the rector of St John the Baptist Church in Maadi, Cairo. "Our church had a good relationship with the Islamic authorities [in Cairo], so we held a number of inter-faith activities, but they were the traditional ones: panel discussions and forums, and you'd see the same people there all the time. I was talking to some of the imams there, and quite frankly we were bored," Chandler admits.

____________________

Read more:

Yazan Halwani: Remembering Lebanon’s great famine with a canopy of words

The state of the art scene in Dubai: a look into how things are going

‘Broken Wings’: Musical of Kahlil Gibran’s masterpiece opens in London's West End

Ashok Mody, who built Sultan Al Qassemi’s family home, on the distinctiveness of Gulf architecture

____________________

What began as a small exhibition featuring works by 20 Muslim and Christian artists soon expanded to include programmes for music, film and literature, and eventually moved beyond the confines of the church to events held citywide. In 2013, Caravan extended its activities into the realm of public art and international exhibitions with In Peace and with Compassion: The Way Forward, an exhibition that featured 50 life-size fibreglass donkeys hand-painted by prominent Egyptian artists.

“We chose the donkey, in part, because it’s an animal that is seen all over the Middle East. Within Christianity, the donkey represents peace – Jesus rides into Jerusalem on a donkey” Chandler explains. “In Islam, the second Caliph, Umar Ibn Al-Khattab, comes into Jerusalem on a donkey, saying that he is entering the city in peace. It’s also a beast of burden, hence the themes of peace and compassion.”

The exhibition eventually travelled to London, where the donkeys were exhibited in St Paul's Cathedral for six weeks, where they were seen by an unsuspecting audience that numbered in the hundreds of thousands. The show set the precedent for the subsequent Caravan exhibitions, most of which have started in the Middle East before moving to Europe and beyond. These include I AM, an exhibition of work by 31 contemporary female artists from the Middle East, which was also curated by Janet Rady. Featuring pieces by artists such as Morocco's Lalla Essaydi, Iraq's Hanaa Malallah, Bahrain's Ghada Khunji and Lebanese artist Zena Assi, the show opened in Jordan before travelling to London. It is now touring the US.

The decision to choose Gibran as the theme for Caravan's latest exhibition stemmed from In Search of a Prophet: a Spiritual Journey with Kahlil Gibran, Chandler's book that was published last year. "Living and working in the region, I was struck by how enthusiastically Gibran is known and loved throughout the Middle East and in much of the West. The East is proud of him and the West is inspired by him, which makes him a unifying figure," Chandler says.

“I think more than ever that there is a need to hear voices that call us to unity and respect and to be inspired to live deeply and generously in our thinking and actions towards the ‘other’, whomever the ‘other’ is, and I think Gibran is that voice.”

Such is the popularity of The Prophet that it has never gone out of print, attracting audiences throughout the West and Middle East. It has sold more than nine million copies in the US alone, making Gibran the world's bestselling poet after Shakespeare and Chinese Taoist philosopher Lao Tzu.

A book of advice that blends elements of Christianity, Buddhism and Sufism, while expounding on matters relating to love and marriage, joy and sorrow, children and the environment, the position of women and the world of work, The Prophet immediately earned Gibran a reputation as a self-made seer – or as one biographer suggested, the Middle Eastern counterpart to eminent Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore.

The Prophet sold out its first printing in a month, and by 1931 it had been translated into 20 languages, catapulting Gibran to a level of celebrity that saw him published in New York literary magazines alongside authors such as Eugene O'Neill, T S Eliot and John Dos Passos. By the 1960s, The Prophet's emphasis on freedom and love helped to make it something of a touchstone for the hippie generation, and its continued success in its 95th year represents nothing short of a cultural and literary phenomenon.

Gibran’s name now adorns schools in Rabat, Morocco and New York’s Brooklyn and Yonkers; there is a Gibran Chair for Values and Peace at the University of Maryland; international symposia are held in the poet’s name; and his life was turned into an animated Hollywood movie.

The author of nine books in Arabic and eight in English, Gibran's words have inspired everything from song lyrics to political speeches. Indira Ghandi and The Beatles readily admitted their debt to Gibran's influence, while John F Kennedy is said to have borrowed from the mystical Lebanese thinker, not once, but twice, in his campaigns and speeches.

For his 1961 inauguration, Kennedy is understood to have turned to Gibran for his now famous words: "Ask not what your country can do for you. Ask what you can do for your country" – which paraphrased a letter by Gibran to Lebanese parliamentarians during the Great Syrian Revolt against French colonial rule in 1925. Before that, the translated title of the letter, The New Frontier, was also used by Kennedy in his acceptance speech to the Democratic National Convention as a campaign slogan in the 1960 Presidential election.

But if Gibran has the potential to inspire and unify, he also has the ability to divide in equal measure, and there are few figures in world literature who have been so successful and so widely admired, but who have also been so utterly derided by so many members of the literary establishment. Described by The New York Times as a "candy metaphysician", Gibran has been more recently described as the forerunner to contemporary writers of inspirational literature such as Paulo Coelho. Both claims

are dismissed as inaccurate and ahistorical

by classical scholar and Gibran biographer Robin Waterfield.

"To think of him as a trivial or unimportant person is wrong in many respects. Gibran is offering a chance for us to aspire to something bigger and better than ourselves, a big vision, but he leaves it up to us to find a way, if there is a way, to make that vision real in our lives," says the author of Prophet: The Life and Times of Kahlil Gibran.

"He obviously hits the mark and has an appeal to a very large number of people, and I don't see what's wrong with that. Most people will simply read the book and perhaps think that it's pretty, but won't do anything about it or let it change their lives, but in a few people it will trigger them to really try to improve something."

That's certainly the case with Caravan and its Gibran-inspired exhibition: it's a project that Gibran would have approved of, Waterfield says.

Kahlil Gibran: A Guide for Our Times is on show at Sotheby’s Mayfair galleries until August 10. For more information, visit www.oncaravan.org