It has taken decades for the West to entertain the idea that Modernist art was actually a group of Modernisms, a splintered movement rather than a single cultural force.

With postmodern criticism and the rise of the world art market, one of those Modernist efforts is finally getting its due.

In Iran, a country whose art was overlooked for far too long by the West, it appears they were way ahead when it came to celebrating such a pluralist approach. From the 1950s onward, its artists were responding to, rejecting and ripping off Modernism as they saw it in ways that seem startling and fresh today.

And in some ways it was no wonder – before the 1979 revolution, the country was going through what Iran scholar Layla Diba, who was in Iran for the preceding four years, says was a “period of great intellectual ambition … a rediscovery of the world”.

With support from the pro-western Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the first Shiraz Arts Festival took place in 1967, bringing the most up to date in dance, performance and music to Iran. Andy Warhol visited Tehran in the early 1970s, the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art opened and the city became a cosmopolitan nexus fuelled by the arrival of Pop Art, Abstractionism and Cubism.

Via email from his Tehran studio, Parviz Tanavoli, the renowned sculptor whose work forms a vital part of the show, writes that, back then, things were “so good that it is hard to believe”. According to him, Queen Farah asked her husband, the Shah, for 1 per cent of the cost of an order of F16 jets to be given to the arts so it could “flourish fast”.Remarkably, Tanavoli says, the Shah agreed.

“This money practically was insignificant, but the queen managed to assemble the largest collection of western modern art in Asia.”

The effect of all these influences is explored in the splendid new show at the Asia Society in New York, Iran Modern, the first international loan show ever staged of modern Iranian art. Diba, who is one of the curators of the exhibition, says the show’s aim is to “challenge the canon of Western art history and create a space for Iranian modern art”.

“Iranian Modern art needs to be counted with all the other non-western forms of Modernism if we’re going to re-evaluate global Modernism,” she says.

“We want to show that contemporary Iranian art has very deep roots, that the Iranian Modernism genesis goes back to the 19th century. We’re trying to change perceptions.”

Iran Modern, a major show that occupies two floors of the Asia Society on Park Avenue, focuses on the period from the 1950s up to the 1979 revolution. There are artworks from 45 public and private collections in the US, Canada, Europe and the Middle East; most of the artists spend some or all of their time abroad through exile or personal choice.

Only one of the artworks on show is actually from Iran, and this was a deliberate choice. Due to the 1979 sanctions, the Asia Society required a special licence from the US Treasury to import it and the curators feared the paperwork could cause problematic delays. They were right: the piece arrived several days after the public opening and was hastily put up.

By far the most exciting section of the exhibition is the first, where the fusion of Modernist ideas and traditional Iranian art is most impressive. Called Saqqakhaneh, a term coined by art critic Karim Emami in 1963 because the Shiite iconography reminded him of figures on public water fountains.Among those featured is Hossein Zenderoudi, who set about creating his own artistic language by searching for inspiration in poor towns for inspiration from charms, zodiac signs and bric-a-brac.

In K+L+32+H+4, he paints an image of himself and a couple with faces and bodies that are completely covered in strange, quasi-religious symbols and with faces that look like alien clocks. It has been described as Spiritual Pop Art, not least because it was created the same year as Andy Warhol’s 32 Campbell’s Soup Cans.

And comparing the two, it is hard not to see the connection between the red crayon smeared across the lips of Zenderoudi’s mystical characters and the brash lipstick on Warhol’s Monroes.

In close proximity is Tanavoli, who felt close to Pop Art at the time as well, though he took a radically different approach, more or less inventing a new kind of Iranian sculpture. Like Zenderoudi’s art, there is something unknowable in Tanavoli’s work that speaks to emotion over reason.

With the sculpture Poet, the onlooker feels like the strange mini-missile shapes emerging from it could morph into anything and that the bulging toes at the top are a loopy nod to Picasso. It sits at the junction of sinister, disturbing, baffling and bizarre – and hits all four remarkably well.

With Heech Tablet (Heech meaning “nothing”) he has created a 1.2-metre-high mini skyscraper that looks like an anonymous tower block or the sinister Ministry of Truth from George Orwell’s 1984.Attached to the bottom is a triple padlock, which gives it an added air of oppression but no explanation as to why it is there.

Innovation in Art is another of his works on display. Created in 1964, it is a picture of a ewer Iranians use in toilets that has been put onto a prayer mat with some pumpkin seeds set above it. Tanavoli says that the use of deadpan wit about Islam was dangerously ahead of its time and caused such quite a stir when it was first shown at the Borghese Gallery in Tehran.

“People were insulted and raised up against the show. The gallery owner was scared and asked me to remove these pieces.

“Although I did so, but it was not enough. A few days later the gallery owner asked me to clean up the gallery from my works.”

The entire show was then shut down and Iran Modern represents the first time since then that that Innovation in Art has gone on show.

Iran Modern also features calligraphy and Abstraction, displays that serve as effective snapshots of a few influential figures, rather than a comprehensive survey. For the most part it is a success with what Diba calls art that is “totally unexpected”. One such is Heart Beat by Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian, the Iranian-born Abstractionist who was friends with Warhol and once gave him a glitter ball. Heart Beat comprises a series of very thin sections of mirror that have been lined up in a haphazard fashion so that they dissect any reflection into dozens of overlapping vertical slices. Some of the glass is coloured so the viewer can see a line, which resembles the beat on a heart monitor. It’s hard not to pace back and forth, marvelling at the abstract illusion of your reflection catching up with you seconds later.

Elsewhere, other artists appear to have even skipped Modernity entirely and jumped to something more properly described as Postmodern. For example, Untitled, by the veteran calligrapher Mohammad Ehsai, looks remarkably like a graffiti tag, although he produced it in 1974, 10 years before street art really took off.

Bahman Mohasses’s macabre sculptures are warped, tiny versions of classical standards such as a pair of wrestlers and a minotaur. But there is also one called Sophie von Esssenbeck, after a character in the gaudy 1969 Luchino Visconti drama The Damned, about a wealthy German family who collaborate with the Nazis.

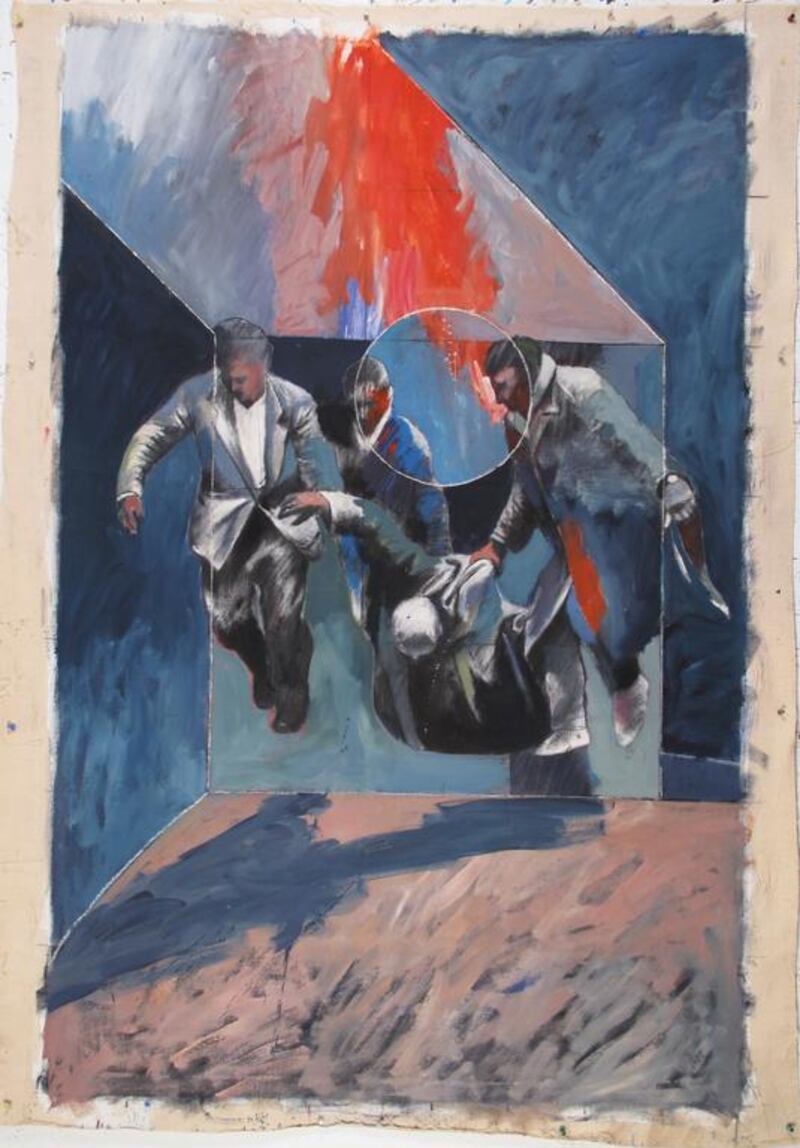

The exhibition begins to falter with the section on politics. Untitled, 1976, by Nicky Nodjoumi, which he painted in New York while in exile, shows three members of the Savak, or secret police, dragging a hooded man along the floor. A circle is drawn over the middle of the painting invoking the sight of a gun and above them frantic red oil markings pour down as if a trapdoor of blood had opened up in the roof. It is stark and oppressive and a sign of the horrors that were to come – and were already happening – but is notable because it has the most bite by a long margin.

The exhibition notes vaguely suggest that “allusions or political interpretations of seemingly apolitical works may be sought and found; given that Modernism responded to war in such memorable and brutal ways, it seems a weakness that this is not explored with more vigour.

In the west, art galleries are traditionally a place to meet, think and share ideas. This is the also the role that Iran Modern can play on the global stage, especially for a younger generation, Fereshteh Daftari, the co-curator of the show, says. “This exhibition is not just for the New York public but I think it is very important for Iranians, especially those born after the revolution.

“This is a period they don’t know much about in Iran or here or abroad. They’ve not had a lot of opportunities to see a curated show about the whole period. It is important they do.”

• Iran Modern at the Asia Society in New York runs until January 5 (www.asiasociety.org).

Daniel Bates is a freelance journalist based in New York.