As Ramin Haerizadeh inspects his latest exhibition at Gallery Isabelle van den Eynde in Dubai, the artist stops, momentarily, to adjust a banker's florid purple-and-gold silk tie.

Rather than hanging straight, it needs to be worn looped over one of the green plastic vegetables that protrude from the back wall of the man's office as he sits behind his desk, resplendent, sporting a plastic beard and fake fur moustache, with his hairy stomach on display.

The banker is the subject of Haerizadeh's delightfully eccentric Even the CEO of HSBC has a Belly Button, a work of art that emerges from its canvas like some surrealist optical illusion, combining collage, photomontage, sculpture and drawing in the process to create a fantastical tableau.

It is part of Haerizadeh's latest solo show, To Be or Not to Be, That Is the Question. And Though, It Troubles the Digestion, which takes its name from a poem by Polish Nobel Prize-winner Wisława Szymborska. Like the vast majority of the works on display, Even the CEO of HSBC has a Belly Button is a project that has taken shape over several years, slowly accruing revisions and new details as it and its creator both age.

"Each piece has its own journey and its own life, but if it comes back from an exhibition and stays with me, then I don't wrap it up and put it in storage, I keep it in my studio and I work on it, recycling it over and again," the softly spoken artist tells me.

"It's about rediscovering the work, but also in the passing of time, say two years later, your knowledge about life has completely changed, so I am not the same person as I was when I first made the work.

"Not only has the world changed, but my mind has changed and I have definitely changed in the process."

A close inspection of the works in the show, the earliest of which dates from 2009, not only reveals the pencilled notes in Haerizadeh's spidery hand that record the date of each modification, but also the extremely layered nature of his work, which has to be seen up close to be appreciated.

A piece such as Son of Godzilla (2015-17) features a background image of the Dubai Metro, an oud box, bits of Blu Tack, a wooden shelf, glass and plastic figurines, fake fruit and teeth and an anatomical human model. It also now sports part of the packing case in which it was transported the last time it was shown.

"It came back from an exhibition in a mover's crate, but when I saw it I thought, 'This is good', so I kept it as it is," the artist says.

Both factors are normally inextricably entwined with Haerizadeh's collaborators, house and studio mates: Rokni Haerizadeh, his brother, and his friend since childhood, Hesam Rahmanian.

All three have lived in Dubai since 2009, when they arrived for that year's Art Dubai, only to find themselves stranded and unable to return to their native Iran.

At first, the exiles lived in Dubai's Jumeirah Beach Residences, and for two years they worked out of a studio in the city's industrial quarter, Al Quoz, near Alserkal Avenue.

The environment and the situation soon began to have an adverse effect on their work, however, so the trifecta decided to move.

"Our work became very rough and angry because of the ambience of the industrial space, so we decided to blur the line between life and art and to have everything in the same place, to live with our art, and we've been living like this for the last six years," Haerizadeh says. "We make a city inside the house, so sometimes we don't need to go out because we bring the city inside the house and make an ecosystem for each other.

"Sometimes we create solo work and other times we collaborate with each other, and sometimes the solo work serves as a way of thinking for the collective."

As a collective, the Haerizadehs and Rahmanian have exhibited internationally since they took up residence in Dubai. Not only did they contribute to the publication that accompanied Rock, Paper, Scissors: Positions in Play, the Hammad Nasar-curated UAE National Pavilion at this year's Venice Biennale. They were also commissioned to produce new work for The Creative Act: Performance, Process, Presence, the second exhibition of the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi collection that was exhibited at Manarat Al Saadiyat earlier this year, and have recently exhibited at the ICA in Boston and Kunsthalle Zurich.

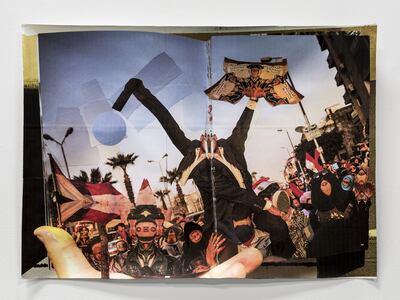

To Be or Not to Be, That Is the Question. And Though, It Troubles the Digestion is Haerizadeh's fourth exhibition at Gallery Isabelle van den Eynde. It features a mix of overtly politically motivated works, such as the collages he describes as still lives that engage with the events of the Arab Spring, and the more ostensibly personal series, First Rain's Always a Surprise, which seeks to locate his mother's and his family's history in a broader social and political context.

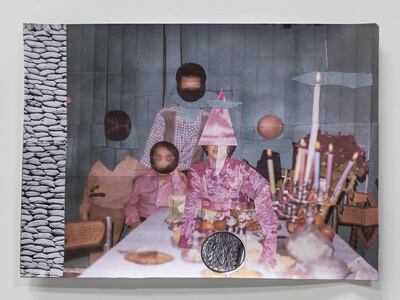

"I started the series in 2012 and based them on my mother's personal archive," Haerizadeh says. "She writes a diary on a daily basis and ever since she was 15 she has always carried a camera with her. So now I have an archive of 60 years of photos.

"They are about a Middle Eastern woman who was part of the first generation to be sent abroad to study, but who then returned to find her life confronted by events – wars and revolutions – and is records of how this has aged her," he explains.

The various collages that make up First Rain's Always a Surprise simultaneously represent a life's journey in pictures and a chronicle of the period. In one, Haerizadeh has used snapshots from his mother's skiing trip in Switzerland in 1961 alongside images of the Iranian revolution, while he and his whole family stand in another, with a central image that dates from the 1980s, transmuted into hieratic, otherworldly sentinels that gaze back at the viewer from another time and another place.

Haerizadeh regards this piece, the largest in the series, as a sculpture, which buckles thanks to the many layers of the collage and his treatment of the paper.

Featuring photographs that have been reprinted, reversed, layered and even washed, the billowing, two-metre-tall image is displayed, unframed but suspended from the gallery wall like a banner, using little more than bulldog clips.

The 42-year-old artist insists that the act of collage is a profoundly political act, something that places his work in a longer trajectory of Dada and Surrealism, and in the company of artists such as Raoul Hausmann and John Heartfield, both of whom used collage as a form of satire and protest; and in their tactility, to the early work of recently Austrian artist Franz West.

"For me, collage as a form is political. Instead of painting something, the use of existing images and putting them next to each other, harshly sometimes," he says, insisting that, ultimately, his work is an exploration of photography and image-making, questions that have become even more important at a time when images and photographs have become so ubiquitous.

"With new cameras and mobiles everyone now is a photographer, and with a new iPhone, everyone can get a perfect image, so what is photography?," asks Haerizadeh, who once trained with revered Iranian photographer Masoud Masoumi. "When I make a collage, I will often take a picture of the collage and then print it, reprint it, reverse it and then use it again in the collage so it has a journey, back and forth, that never finishes.

"Sometimes I use old mobile phones, old scanners, so that it gives a different texture to the main picture, but most often, I use found photography, taken by others. My aim is to develop a new way of doing photography."

The irony in Haerizadeh's statement is that his work is notoriously difficult to reproduce. The subtle layering, mirroring and treatment of his collages and photo sculptures has to be seen up close and in person to be appreciated. Once a viewer is in this situation, the challenging juxtapositions soon melt away as their compositional sophistication come to the fore.

______________

Read more:

[ Emerging UAE artists are unafraid to challenge in the latest SEAF show ]

[ Pouran Jinchi’s ‘Line of March’ to make world debut in Dubai ]

[ Art exhibitions in the UAE: what to see now the new season is here ]

______________

A rare thing, Haerizadeh's collages repay close and repeated attention, and what is more, they actively encourage viewers to think and feel, as well as to look. Eccentric and open-ended they may be, but they also represent a masterclass in the craft of image-making. Pay close attention and you will see the subtly layered story of a region, a diaspora and a generation. Challenged you may be, but you will not be disappointed.

To Be or Not to Be, That Is the Question. And Though, It Troubles the Digestion runs until November 2 at Gallery Isabelle van den Eynde, Alserkal Avenue, Dubai