When the protests in Cairo's Tahrir Square exploded in January last year, Jason Bereswill was working in his large, airy studio in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, watching television and reading news reports online. With a friend's Facebook updates from Cairo, reports filed by journalists from the scene, and a steady stream of photographs appearing on Flickr and CNN's iReport, Bereswill could follow events in something close to real time. History was unfolding, and he was there - even though he had not yet left the confines of his studio.

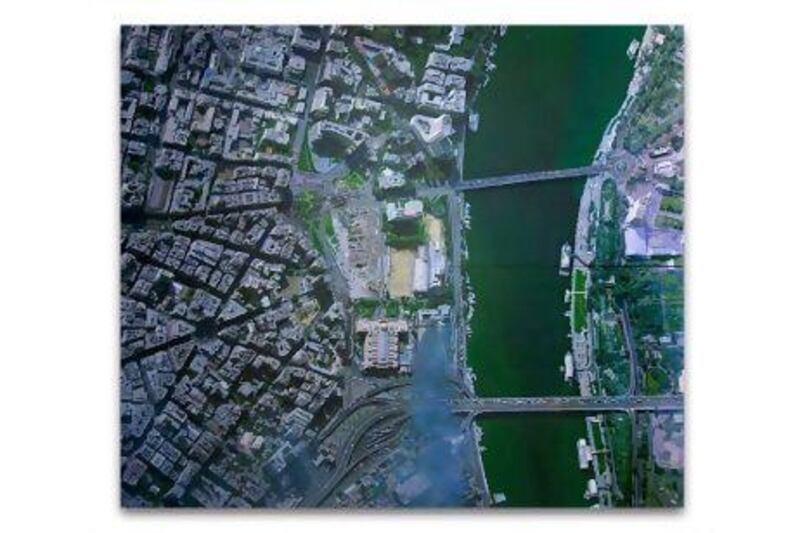

Inspired by what he was seeing, the 31-year-old artist began painting a large-scale image of Tahrir Square as viewed from overhead, a satellite image of a city in turmoil. Bereswill was compelled by the tumultuous events taking place in Cairo, but also by the images themselves. The legions of cameras surrounding Tahrir Square, belonging to photojournalists and protesters alike, sparked his interest, as did the almost immediate sensation of information overload. "I was really aware of the technology that was being used to organise how everything was put together, how it was being broadcast out to the world," says Bereswill.

Photojournalism had been the implicit subject of a previous set of works by Bereswill, inspired by a pair of matched images he had stumbled across in two separate surf magazines. Determining that they captured a single instant from two different angles, Bereswill eventually uncovered eight different photographs of the same surfer, taken within the same second, and created a series of paintings inspired by the images.

The paintings are undergirded by a bittersweet sense of a passing moment in journalism, where the work of the professional - Bereswill's father is a photojournalist - is replaced, and to an extent undone, by the amateur: "For me, they're about the death of photojournalism as an industry." Photojournalism was about sending someone to document distant events, and Bereswill's paintings are, among other things, about being on the receiving end of their work, and wondering whose images these were: "Whose experiences are these now?"

Bereswill's Arab Spring series, which included Protests at Tahrir Square, Cairo, Satellite View, January 29, 2011, was one of the highlights of the 2011 Abu Dhabi Art fair, offering an artistic perspective simultaneously distanced and immediate on the events roiling the region. It was Bereswill's third year showing paintings in the capital under the aegis of the Tony Shafrazi Gallery in New York, following a 2009 series of paintings executed on-site at the fair, and his 2010 show of aerial images of Abu Dhabi inspired by photographs pulled from Google Earth. The 2010 Abu Dhabi paintings marked Bereswill's first time breaking away from his previous routine of executing hasty sketches and taking snapshots of places he visited, preparing for the longer, more arduous work of painting on a larger canvas. Bereswill was intrigued by the satellite imagery for its peculiar modernity: "I could make paintings that were very abstract on the surface, and yet still be accurately depicting the place." Protests is a deceptively placid overhead view of downtown Cairo, with viewers left to decipher the image and read its clues - the people streaming across its bridges, the smoke swirling up to blur the bottom quadrant of the painting - as to what is taking place. "I tried to do something on the scale and ambition of a history painting, which is generally on a grand scale, and that is usually done years [after the event]," says Bereswill. "But [I was]trying to do that while the events were taking place."

Bereswill saw Protests as the fulcrum around which a new set of images could be drawn from the turmoil of the Middle East and the democratic medium of the internet in equal parts. Protests would be an "anchor to anything I could show - the one big piece in the centre that would have a network of images around it," says Bereswill.

"It's really to do with a particular moment in time," says Hiroko Onoda, director of the Tony Shafrazi Gallery. The other paintings in the series are like snapshots, capturing moments rescued from the endless well of online images and turned into something resembling landscape painting. Bereswill was less interested in the more obviously eye-catching images of chaos and destruction familiar from the front pages than quieter, more contemplative moments. "I created my own criteria for how I wanted to deal with these images," notes Bereswill. "I started thinking, as I was looking through these photographs, 'What would Edward Hopper paint in this situation?'" Hopper's influence is obvious on paintings such as A Libyan Gas Station and A Hole in a Wall, their stillness, emphasis on landscape over human figuration, and even, flat light owing much to Hopper's depictions of rural America. The difference, for Bereswill, is that we are presented with images of countries such as Egypt and Libya in the midst of politically fuelled chaos. In many of these paintings, we seem to arrive on the scene just after the excitement has ended, wondering what has taken place in these denuded spaces, left to put the sparse clues together. What has caused the enormous gap punched in the wall of what looks like a home in A Hole in a Wall? We are as clueless as the three men on the scene in the painting, peering in the windows and studying the rubble.

"I felt it was too easy to go for the most sensational images," says Bereswill. "A lot of the images I went with had a haunting feel to them. I was trying to paint them as though I was painting en plein air. I tried to paint them as though I had gone and set up in this place, and made a quick painting on site. I would give myself time limits for each painting." For A Storm Drain in Libya, depicting the hiding place where Muammar Qaddafi was discovered in October, Bereswill completed the majority of the painting, except for the trickier Arabic-language graffiti (the artist does not read Arabic), in 20 minutes. Painting becomes a kind of on-the-scene reportage, filtered through the simultaneous intimacy and distance of the internet. "I was thinking of it very much as a still life," notes Bereswill, "because the images were coming to me as these framed scenes." He sees his work as a painterly version of journalism, his task "going out in the field and gathering information and presenting something better informed."

Bereswill's first show at the Tony Shafrazi Gallery, in 2009, had him painting a series of large-scale canvases in person in the gallery. He would begin by imprinting a photo or drawing on the canvas, which he would then paint over using his photos and sketches for guidance. "People are seeing the mistakes," says Bereswill of painting in the gallery. Visitors could watch him paint, or look to the piles of back issues of The New York Times piled at the foot of each painting for visual evidence of the number of days he had been at work. "He would always come in with the paper and the coffee," remembered Onoda, "and it just became a part of the exhibition." The Abu Dhabi show was not solely composed of Arab Spring images. Instead, Bereswill opted to also exhibit False Sequence (Serra from Above) and Bilbao From Above (Guggenheim, Puppy, Maman), views of a Richard Serra sculpture and Frank Gehry's Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, as seen from directly overhead. The satellite perspective makes these simultaneously images of instantly recognisable landmarks, and something entirely unrecognisable. The paintings cannot encompass the scope of the visual information we already have about these familiar objects. The show also included a number of Bereswill's Hole works: a series of paintings of indentations in the ground that could be displayed on the wall or floor. The holes are metaphysical commentaries on Bereswill's role as artist-journalist: "I'm aware of my distance from the immediate events, and at the same time, I'm creating something that literally is a hazard, and can easily be tripped over." (When they were still in his studio, Bereswill regularly tripped over them himself.)

The Serra and Bilbao paintings are reminders that paintings are sometimes incapable of capturing a multivalent reality too complex for a flat canvas. At the same time, the Arab Spring series is Bereswill's attempt to revive the history painting, as if to argue that having mostly abandoned its interest in current events, painting has forgotten that there are some realities just complex enough for the canvas. History painting, for Bereswill, was about "making something before the event is really closed, before the results are in. And investing this huge amount of material and time to get it done. History painting doesn't have to be a retrospective thing."

Saul Austerlitz is a writer in New York. His work has been published in The New York Times, Los Angeles Times and Boston Globe.