One of the more noteworthy eureka stories in GCC curatorial legend is that of Sheikha Hoor Al Qasimi and her trip to Documenta 11.

In 2002, Al Qasimi, at the time 21 and studying painting at the Slade School in London, was accompanying her father on a cultural tour of Germany. He went to Mainz for a day, and she to Documenta 11, the agenda-setting art exhibition that takes place every five years in Kassel. That year happened to be a key one for the show. Put together by Nigerian curator Okwui Enwezor, the exhibition drew artists from across the world and challenged a western-centric art scene to look beyond its confines. It would have been an extraordinary exhibition for anyone to start on.

“I had never been to any biennial other than the Sharjah Biennial before,” Al Qasimi tells me. “And so I went, on my own, and it changed my life.

“I said to my father, ‘What happens with our biennial? Why isn’t our biennial like this? I just want to see, I won’t interfere’,” she continues, laughing – because she did interfere.

After being appointed to the committee overseeing the Sharjah Biennial, which her father, Dr Sheikh Sultan Al Qasimi, Ruler of Sharjah, established in 1993, she eventually took the exhibition over and turned it into an important stop on the art world calendar.

In 2009, frustrated with the stop-and-start visibility of hosting biennials, she created a foundation that hosts about 10 exhibitions a year, many of them well-researched, major retrospectives of figures who have been ignored elsewhere. The biennial and foundation also began a number of education and funding schemes – in film, music and art – such as the Production Programme, which gives US$200,000 (Dh734,500) every two years to support the making of artworks.

___________________

Read more

[ The influential female voices shaping the UAE art scene ]

[ Dancing in the rain at Sharjah Art Foundation’s 'Rain Room' ]

[ Sheikha Hoor climbs Art Review’s Power 100 list ]

___________________

In 2010, two of the works supported by the programme – by Bani Abidi and the collective CAMP – ended up in Documenta 13, not even a decade on from Al Qasimi’s first visit to Kassel. And today, Enwezor himself arrives as a collaborator at Sharjah Art Foundation, co-convening a conference that will help launch Al Qasimi’s latest, flagship project, the Africa Institute, which is devoted to exploring the art and ideas of that continent and its diaspora.

A multilinguist in a multilingual town

Sharjah Art Foundation has also developed a unique position of both local and international relevance. It has bureaus dotted throughout the emirate, in villages such as Kalba, Al Madam and Khor Fakkan, and at the same time their shows are often followed by similar ones abroad. After the Sharjah Art Museum’s Ibrahim El-Salahi show in 2012, for example, which Al Qasimi helped instigate, Tate Modern hosted a show of the Sudanese painter in 2013. And the stunning selection of paintings by the Turkish-Jordanian artist Fahrelnissa Zeid, glimpsed in Eungie Yoo’s Sharjah Biennial of 2015, forecast the 2017 London retrospective of Zeid’s work, again at Tate Modern.

“It’s good that Sharjah can be the platform to give these artists an opportunity,” Al Qasimi says. “But it’s also frustrating that western art institutions won’t do it until they see someone else doing it.”

Though Al Qasimi avoids the spotlight, speaking to her, it is impossible to ignore a synergy between the foundation’s internationalism and Al Qasimi’s own remarkable cultural literacy. She speaks, for example, nine languages. Four fluently: Arabic, English, Japanese and Mandarin; and five conversationally: Tagalog, French, German, Russian and (in a surprise twist) some Polish. She took up Japanese when she was studying at the Slade in London.

She sat at the kitchen table and announced one night that she was going to learn Japanese, and began classes at University College London – where, though coming to the material totally fresh, she was top of her class every year. And she took inspiration from the city as much as from her studio. “I like to observe,” she says. “I would walk around the city, just walk and walk and walk.”

She learnt Mandarin next, and when she arrived in Beijing, she says, someone asked how long she'd been living there. "One day!" she told him, delighted.

This natural ease with languages seems to have seeped into her character, giving Al Qasimi – ever the observer, walking around the city – a Zelig-like role of eternal attentive outsider. “Wherever I go, if I speak their language, I’m like the immigrant in their society,” she says. “In Germany, if I speak German, they think I’m Turkish. In Paris, they think I’m Moroccan. In England, they think I’m Pakistani. In Japan, they would say, ‘Are you half?’ Someone thought I was from the Indian community in Trinidad and Tobago.” In Senegal, she said ‘thank you’ in Wolof, and someone thought she was from the Lebanese migrant community there. “And I quite like that. I like when people ask me where I’m from. And if they guess, I say yes.”

Bootstraps early days

As with the Africa Institute, which opened this week and resumes the history of the Africa Hall – founded in 1976 by Sheikh Sultan in recognition of the many ties between Sharjah and Africa – Sharjah has always maintained international connections. Al Qasimi sees herself as only building on what has already been accomplished.

“We’re not starting from scratch, and we know the layers,” she says. “You have to know what’s there before you put anything in. We know who we are and we need to see what suits us in this environment.”

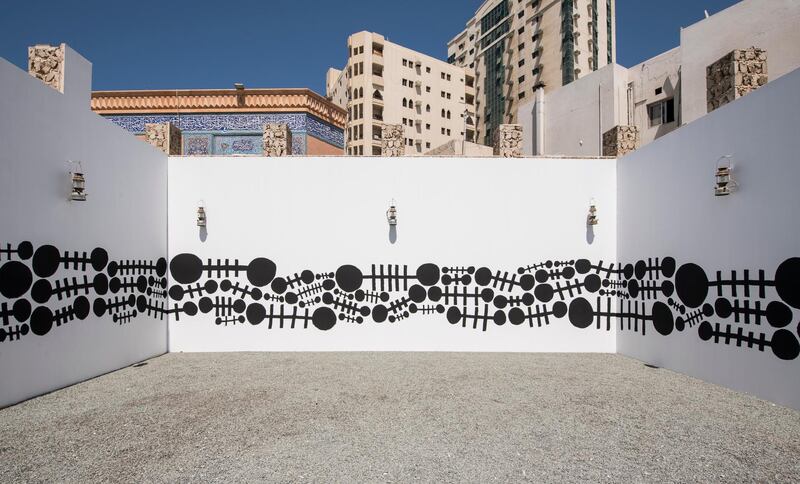

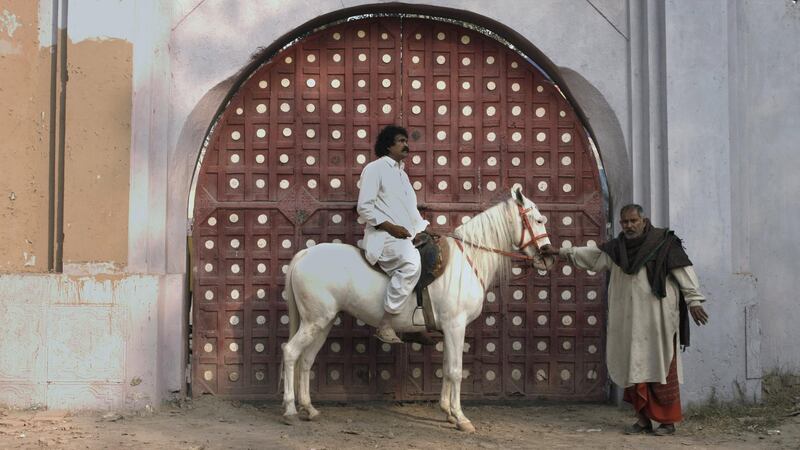

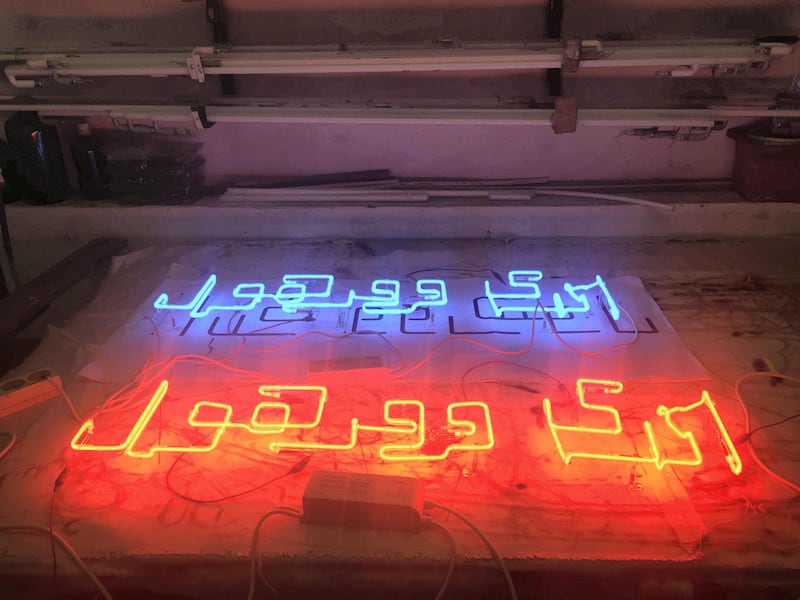

The Production Programme turns 10 this year, with awards given to artists Ghassan Salhab, Doa Aly, Taus Machacheva, Joe Namy, Mounira al Solh, Fatma Belkıs and Onur Gokmen, who will split the $200,000 among them. And, opening this weekend along with its autumn shows of work by Frank Bowling and Ala Younis, the Foundation hosts an exhibition of previous winners, such as Raed Yassin, Rula Halawni, Basir Mahmood and Hoang Nguyen.

When I meet Al Qasimi to discuss how the programme and the foundation have evolved, she is sitting with a binder of applications for the next Production Programme, making notes in Fen Cafe, the coffee shop in the warren of traditional Gulf architecture that Sharjah Art Foundation has transformed into its exhibition spaces. "I go through all the applications and I make the short list," she says. "I do the same with the short film submissions. It takes ages. If a film is not 100 per cent there, but there's some potential, I worry that someone else might not want to give it the chance."

Al Qasimi has been hands-on from the start. She grew up visiting the biennial, and had her first job at 16, teaching drawing in Bait Alserkal – which is also now one of Sharjah Art Foundation’s spaces. When she took over the biennial, in 2003, she had a team of just four people: her and three technicians. “I did everything. I swept the floors, hung the labels, learned InDesign to do a book, made a website – not a very good website, but a website!”

Al Qasimi’s position as the daughter of the ruler of Sharjah makes this story less of a golden-hued reminiscence about the foundation’s lean early days, but a reflection of the line she has had to toe, where she knows that just as her role opens opportunity, it also meant, as she put it, in the beginning “no one was going to take me seriously”.

By this point, they do. Where there were once four, now there are 222 members of staff at the Sharjah Art Foundation, most of them in the education department. In addition to its main spaces in the Heart of Sharjah, the foundation is building a new structure near the American University of Sharjah, in the city’s University City area, to house its substantial permanent collection, and has launched a new film festival that will start this December.

She continues: “By now, everyone knows what Sharjah Art Foundation is about: the artist and the public.”

Sharjah Art Foundation’s new exhibitions are now open, including Ten Years of Production Programme at Al Hamriyah Studios