Areej Kaoud creates art as a result of her anxiety. And in stressful times like these, the works in the Palestinian artist’s first UK solo exhibition, Mishmish (Apricot), seem more relevant than when it opened last month.

The show was cut short in light of museum and gallery closures amid the coronavirus crisis. But Indigo & Madder in London has made the exhibition available on its website for people to explore. "Her work is brave and highly political and that is what drew us to her practice," says Krittika Sharma, curator at Indigo & Madder. "Her exploration of living in a state of anxiety and using it as a tool for survival, which helps prepare for both known and unknown dangers, is very compelling."

Kaoud's works present what she calls "a political play on words". Her paintings of fruits are immobile and sober against their bare backgrounds. She says they reference Belgian Surrealist Rene Magritte's 1929 masterpiece The Treachery of Images (This Is Not A Pipe), in which an image of a pipe is accompanied by the text: "This is not a pipe", and shatter the traditional tromp l'oeil effect of still-life paintings, while calling for the viewer's undivided attention.

The theme of anxiety is explored through wordplay. A piece of fruit, painted in vibrant colours, is pitted against a white canvas and accompanied by Arabic text beneath the image. For Kaoud, wordplay is “a way of reframing the perception of a subject”. For example, a painting of an apricot appears with text that poignantly reworks the Arabic noun for the fruit from “mishmish” to “mish mashee”, which translates to “I am not leaving” or “it is not okay”. Kaoud continues that play on words, but this time in a painting of a lemon, labelling it “mish mistwiya”, meaning “it’s not ripe”.

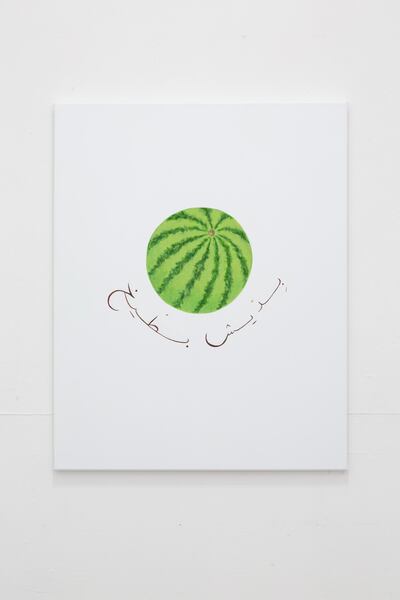

She also incorporates wordplay in her performance art. In You Want Watermelon (2020), which she enacted on the exhibition’s opening night, she personally cut and offered a slice of the fruit to each visitor. The Arabic word for watermelon, batteekh, is also a colloquialism meaning nonsense – the play on words demonstrating that she was distributing nonsense. Visitors weren’t permitted to resist the gesture; Kaoud did not walk away until the viewer accepted the watermelon from her.

Though the performance was cleverly filled with comedy and lightheartedness, the scenario was an exploration into the theme of control and submission when choice is removed. “It was a practice of establishing control and building trust, and realising what is being offered is for survivalist reasons,” she says.

The performance complemented one of the acrylics on show, I Don’t Want Watermelon (Bideesh Batteekh). Typically, when this phrase is used in conversation, it reiterates a person’s desire to be spared the nonsense, she explains.

The show also includes a pair of audio works: one that is performed in Arabic with an English translation, and another that is performed in English. Written and recited by Kaoud herself, the recordings are meditative and made more intense through juxtaposition - the pendulum swings between the banal, such as paper cuts and her choice of nail varnish, and the more serious, such as the probability of death and our unpreparedness for it.

Kaoud has previously exhibited and performed at Tate Modern in 2018 and at Art Dubai in 2016. As a resident of London, she hopes to be part of a larger conversation in the diverse arts scene. As Sharma explains, it is about introducing new voices to London’s contemporary art canon. “We hope to work with more artists from the region and promote stronger cross-cultural discourse.”

Mishmish is available to view at www.indigoplusmadder.com