Art fair season arrives in the UAE like a tropical storm: first the far-off rumblings, a roll of timpani to heighten anticipation. Sotheby's launches its Doha operation with a set of simpatico auctions: jewelled watches and collections of Islamic, orientalist and contemporary art. The Contemparabia bandwagon, an art tour designed to allow, in its own words, "international collectors, curators, museum directors and media to experience the extent of cultural activities in the Gulf", stops in. The tour party - and it's entertaining to join this horde of high-end gallerists and art advisers trundling about by coach - is en route to a tour of the galleries at Doha's cultural souq and then to the first phase of the Global Art Forum at the Museum of Islamic Art. From there, the crescendo: they'll descend on Art Dubai, the Sharjah Biennial, Al Ain and the Abu Dhabi International Book Fair, buying, selling, gossiping, building scenes, reputations, alliances. Then, as quickly as they came, they'll be gone, leaving us in the Emirates with our ears ringing and a few green shoots of inspiration poking through the leaf litter of dropped business cards.

Sotheby's first: the auction house has taken up a temporary residence in the tennis courts of the Doha Ritz Carlton, where it has rolled out its heavy artillery, both in terms of personnel and product. During the press preview Bill Ruprecht, the group's CEO, was working the floor, flanked by deputy chairmen for Europe and Asia and specialists for each of the categories in which sales were being held. "The Middle East has to be looked at very seriously," Henry Howard-Sneyd, international director for new markets, explained: "We're looking for areas where there is wealth, where there is individual wealth as well as government wealth, that could be interested in the arts, and the Gulf is the obvious place..."

Neither did the lots themselves seem to leave much to chance: a wide selection of luminous works in the ever-controversial orientalist tradition (mainly from the Continent and including several characteristically luminous pieces by the Austrian painter Rudolph Ernst) were the most daring items on display. The Islamic art sale, meanwhile, was perhaps a little overshadowed by the magnificent Baroda carpet, the jewelled rug assembled from more than two million pearls on the order of Gaekwar Kande Rao, the 19th-century maharaja of Baroda. But for those able to tear their eyes off it, there were exquisite pieces lurking in its penumbra: a gold and silver mamluk bowl; an ornamental Moghal dagger; a 10th-century North African vellum bearing suras in Kufic script.

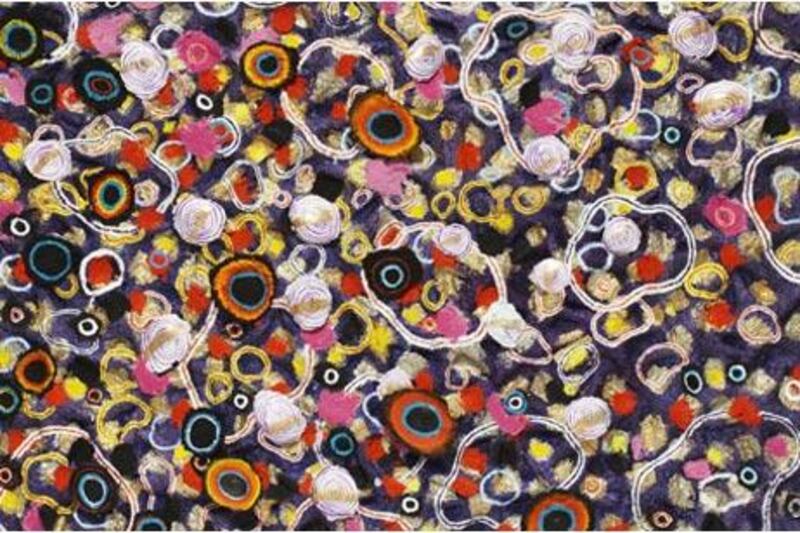

Not even Damien Hirst, who selected his own works for the sale, could disrupt the forcefield of judicious good taste that cloaks the contemporary art section. His dead butterfly collages have always been the best-looking items in his oeuvre, and the three 2008 pieces he picked out for the Doha sale are as decorative as anything he's produced: big, sumptuously coloured, enriched by nature's inimitable talent for detail, they're a good fit for a broker testing the water in a new market. As Saul Ingram, the managing director of the contemporary art department for Europe, explains: "for an international audience, they're quite easy... You can be overwhelmed as you stand in front of it by the beauty of it, but it doesn't take a huge amount of art-historical knowledge to really understand the piece."

Set alongside a sepia-ish Jackie Onassis by Andy Warhol, an uncharacteristically delicate Gerhard Richter canvas and, from Anish Kapoor, a great gleaming stainless steel dish that shifts from violet to blue as you move in front of it, and the spirit of restrained aestheticism becomes apparent. The most outré works are probably the kitschy glitter-and-icing confections from the Iranian painter Farhad Moshiri, also the biggest name among a dozen or so from the Islamic world, though the Palestinian artist Mona Hatoun's bitterly satirical sculptures - a welcome mat fashioned from pins; crutches made of rubber - ran a close second.

"The way we wanted to do this was to create something that was quite beautiful and not controversial..." said Ingram, "so we were very careful about what we selected." There was, however, one pleasingly left-field touch: the invitation of the French sculptor Bernar Venet to deliver an account of his career, assisted by slides of his work. As his entire corpus consists of wiggly lines and bent rods of various kinds, his story was necessarily one of repetition and incremental advance; with each barely distinguishable slide he bemused the audience even further.

Explaining, for instance, how he came to diversify from his early work with arcs and cords of circles to the "indeterminate lines" of his later career, he cheerfully related, in thickly accented English, this epiphany: "I thought, what about making a line that is not determined mathematically? A free line. And I thought: no, I cannot do that, because people expect me to do a certain kind of work. And I remember dealers telling me: 'Bernar, forget about it. People are not going to take you seriously if you get into something very free like this.' But I made one anyway. I looked at it for one week, two weeks, and then I decided I would just go on and see." It all turned out for the best in the end: the opening price for Four Indeterminate Lines, included in the sale, is a highly respectable $400,000 (Dh147,000).

Several other visions of the relationship between art and money were provided the following day at the Global Art Forum, an international talking-shop for gallerists, heads of institutions, artists and assorted culture professionals, who were convening to share their ideas about the future of art in the region and beyond. During a panel discussion about how museums can increase their audiences, Max Hollein, the director of no fewer than three museums in Frankfurt told an excellent story about how he managed to get the best out of the devil's bargain of corporate sponsorship.

When his Städel Museum was looking to launch a contemporary art exhibition on the subject of commerce, it entered a partnership with the supermarket chain Galeria Kaufhof. Except that Städel didn't accept any branding from Kaufhof; on the contrary, they plastered the shops with the gallery's promotional material. When Kaufhof asked for a work of art to sit in their store, Städel got the American conceptual artist Barbara Kruger to create a huge hoarding for their storefronts reading "Du Willst Es, Du Kaufst Es, Du Vergisst Es" ("You Want it, You Buy It, You Forget It"), a kind of memento mori amid the Arcadia of mass retail.

Despite initial misgivings, the supermarket went for it, to Hollein's surprise. Indeed, by the time he had finished with them they were carrying his slogans, handing out Städel-branded shopping bags and imitating his satirical lowest-common-denominator ad layouts. That's the way to do it. There were several other lively discussions during the course of the day: Oliver Watson, the Museum of Islamic Art's chief curator caused a stir for his claim that Islamic art and contemporary Arabic art were roughly as different in kind as the work of Picasso from that of the African tribal artisans whom he imitated, and that therefore there was unlikely to be a permanent home for modern stuff in his museum. Indignant challenges to this declaration were still being offered two debate sessions later. By contrast, Marc Olivier Whaler, the director of the extravagantly hip Palais de Tokyo in Paris, brooked no dissent at all when he said that he would "never, never" engage an art historian to help audiences make sense of his exhibitions since the indirect approach was so much more effective. Silence may not have implied agreement here, however: his own approach was dumbfoundingly indirect. In illustrating the difference between a Duchamp-style readymade and an ordinary household object he suggested by way of analogy the cyborg replicants from the film Bladerunner. In some of his shows ? whether actual or hypothetical ones wasn't clear ? he explained that "there is nothing to see but you are bombarded with electro-magnetic rays". The atmosphere he strove to create in his museum was that of "a parallel universe". He very likely succeeded in increasing the Palais's audience on the spot, from among his intrigued listeners.

Of course, all of these cultural tributaries are set to pool in the great basin of Art Dubai, hosted at the Madinat Jumeirah. This year it's bigger than ever, with around 70 international galleries taking part. The Global Art Forum continues there today with discussions of the all-important artist-collector interface, and the Contemparabia caravan rolls on, through Dubai to Sharjah. For the local gallerists this is a marathon week, and few can have hit it at so frantic a pace as The Third Line. I caught up with Claudia Cellini, the gallery's co-director, at her Doha branch as she played host to the Contemparabia tour. What was her coping strategy for getting through the week to come intact, I asked? "A lot of caffeine," she deadpanned, "and flats" - this said in four-inch heels. "We kind of killed ourselves last week because we had Youssef Nabil's opening, and we hosted a dinner party at my house for about 45 people. And the next day there was a big event for the UAE's pavilion that I had to be there for..." Following the Doha events, the Third Line team were heading straight to Dubai. "We're missing the Bastikya Art Fair opening tonight," said Cellini, "which is too bad because we have a really great solo show by Ebtisam Abdul-Aziz. You can't be in two places at once..." A crowded schedule, I said weakly. "I haven't even told you about the books that we're launching this week," she replied. "And I haven't told you about the talks that we're hosting. And I haven't told you about the party that we're having on Thursday night, for the Sharjah Biennale, with Bidoun." It sounds like Dubai's own most industrious rainmakers are intent on taking the place by storm, too.

elake@thenational.ae