In new exhibition Out of Focus / Union, the Farjam Foundation addresses conflicts between bordering nations, orienting its geographical scope a few degrees east of the Arab heartland. Pairings include India and Pakistan, Iran and Iraq, and its argument is that these countries share more than what divides them.

This endorsement of commonalities is signalled by the show’s first work, a cascade of white tracing paper imprinted with the word “nafas”, which means “spirit” in Arabic, Urdu, and Farsi.

"I have tried to create a visual representation of breathing," says Afshan Daneshvar of her work, which sways gently as one approaches it to read it. "In today's world, people are so immersed in technology and the virtual space that they have stopped using their senses to enjoy the beauty of the real world around us."

The Dubai-based Iranian artist was mentored in calligraphy by her father, and this work, which unites three contiguous cultures through a reminder of their essential human nature, is inspired by the Siah Mashgh, or calligraphy drills, which consist of the repetition of both words and letters.

The show also creates some significant groupings. A floor installation on the theme of migration by the Indian artist Owais Husain, for example, keeps company with a deliberately inscrutable large-scale drawing by the Pakistani artist Imran Channa, and cattycorner to that, an image of two veiled women from the Iraqi artist Halim Al Karim.

Husain's installation, Inventory of Tradition, is a collection of flattened suitcases rendered in metal, with flat-screen TVs in the cases that play soothing footage of leaves rustling or water gurgling. Ornately carved metal screens are strewn over the TVs and cases, obscuring the footage in parts.

The work speaks about migration and movement. Husain calls the suitcases a "vacuum compression" of migrants' belongings.

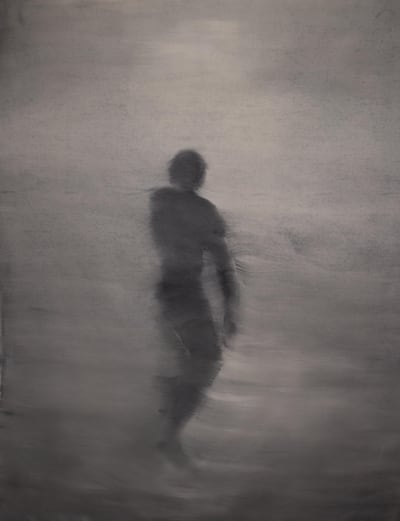

The screen's partial covering of the televisions is picked up in Al Karim's signature use of blurred images, which he creates through a variety of techniques: he shoots his pictures out of focus; places a gauzy scrim – usually silk fabric – over the lens; adds layers of wax and acrylic to the negative of the photograph; or uses a printer that produces a grainy texture.

Goddess of Beirut shows two women covered by long white veils that, generations ago, were worn for mainly social reasons in Lebanon. Al Karim has said he uses the blurred effect to obscure the temporal specificity of the photos: they could be from 100 years ago or 10.

The Iranian painter Chahine Khosravi's works, in greys, dark greens, and ochres, also show figures obscured – in this case, almost wrestling to emerge from the same brushstrokes that adumbrate their forms. And in one of the standout works of the show, time / memory / landscape, the British artist Saad Qureshi has created a rocky landscape – perhaps of Mars, or the moon – out of brick dust and charcoal.

Although the individual works are strong, as a whole the show doesn’t hang together. Its title links visual impairment to the idea of union – generally suggesting that many border disputes are matters of perception, and a shift in focus would bring out what’s shared.

That’s an oddly literal idea, particularly as a focus on vision is oftentimes the problem in identity politics, reducing a person’s character to their visual identity. Diminished vision doesn’t seem the answer either. There are few benefits to knowing less.

The works here are mostly drawn from the impressive private collection of the Iranian billionaire and philanthropist Farhad Farjam – whose collection of manuscripts and Islamic art is extraordinary – and the exhibition tackles an enormous political subject with very little contextualisation for the visitor.

There is a sense, too, that the artists were asked to speak for their countries – or even ethnicities – instead of the focus being on their works. It's a little unfair to point it out, but one commonality that all this work shares, regardless of subjects or style, is its familiarity with an international art lexicon, developed and refined in art schools, on the market, and in international exhibitions. The kind of geographical specificity the exhibition's premise asks for is no longer a given.

When we spoke about his work, Husain, who addresses questions of identity, spoke frankly of this facet: "When I began as an artist, in the 1990s, there were four different zones in India, with different art schools and different dogma," says Husain. "Each one had a different iconography. And the artist from that particularly community shared that iconography and started a language or a library that defined the region. These libraries existed in all parts of the world.

___________________

Read more:

‘Made in Tashkeel’ celebrates the gifted artists it has championed

Nicky Nodjoumi’s satirical pieces on display at rare exhibition in Dubai

The remarkable career of Jordanian artist Mona Saudi

___________________

"But with globalisation, those libraries have disappeared, and there's a singular library – it's almost like a monopoly of a library. It doesn't matter where you are from, besides carrying an accent. There is a kind of uniformity that is shared on a larger scale."

But, he continues, "Is it such a thing wrong? Is it so bad? It's a constant conversation."

Out of Focus/Union poses questions of political identity on the macro scale, but reveals instead that the artistic identity is already in flux and perhaps productively out of focus.

Out of Focus/Union is at the Farjam Foundation in DIFC, Dubai, until the end of June