On the outskirts of Algiers, the promise of a slick, modern life is at a standstill. Far from the inner-city Kasbah, and beyond the faded colonial-era apartments of the central business district, an interlocking mesh of cranes casts shadows on to half-built concrete structures in the suburbs.

Some sites are skeletons, scuppered by failed developers. Others are finished, but isolated from the greater urban fabric of services and amenities. Even the finished high-rises seem to have dated rapidly.

But this style of building really is not all that new. It is the tail-end of the dream of modernism – the utilitarian concrete hutch, thrown up quickly to tackle the overflow of ever-increasingly crowded cities and coated with all the brutalist flourishes of architecture found on skylines from Manila to Marseille.

The artist Driss Ouadahi's solo show, Breathing Space, at the Lawrie Shabibi gallery in Dubai, explores the implications of these social housing projects. Ouadahi's paintings question the temperament of an age that would allow such an urban affront to proliferate – whether in direct examinations of such buildings, or barbed-wire fences rendered with an oppressive exactitude.

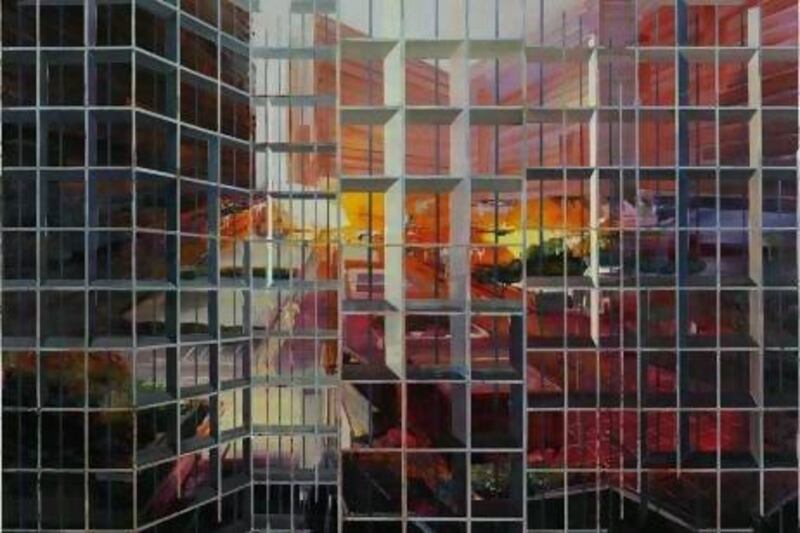

In the best works here, the artist paints hard, grid-like lines on to his impressionist vision of the modern cityscape. It’s like looking into the mirrored windows of a gleaming new tower, seeing the reflection of some anonymous high-rise suburb in misty, washed-out tones.

In other images, these grid lines seem embedded into their surroundings, and we have the sensation of viewing the city from inside one of its half-built concrete cages.

We occasionally glimpse flickers of disorder in what appears like an otherwise sedate scene. In Nightfall (2011) there are glowing fires that flash from street-level, like burning cars. We don't know where they are coming from, and the building's surface in the foreground of the painting makes us feel even more distant from what is going on. While connections can be made with the Arab Spring, there's also a more general, metaphorical disorder implied – a frustrated outburst of colour in an otherwise atonal environment.

Ouadahi was born in Casablanca, Morocco, to Algerian parents, and studied architecture in Algiers from 1979 to 1982. His honed, draftsman’s eye has never left his art, but the bright traditional building forms found in the south of the country were impressed into his early abstract colour works.

After graduating, the artist moved to Düsseldorf and enrolled at the city’s esteemed Kunstakademie, at a time when Gerhard Richter was on the Fine Arts faculty. Ouadahi, then still working on his expansive colour fields, was bewildered by late-1980s, early-1990s German art. “The work I was seeing was very dark, gloomy and expressive,” he says. “I came from a country of bright colours, and I was a bit scared by what I saw at first. But I was looking for a way to give my identity a texture, and a body.”

During an artist’s residency in Marseille, the artist progressed into a style of painting that finds its full articulation in this show.

“Marseille is a photocopy of Algiers, because the same architects – like Fernand Pouillon – worked on both cities,” he argues. While similar in shape and form, the city also has a lot of social housing, home in part to many immigrants from North Africa. “That’s how the reality of Europe grabbed me. Through architecture I found some connection.”

From this, Ouadahi began creating boxy, three-dimensional paintings that have an effect like that of standing in a courtyard of skyscrapers. But in his Lawrie Shabibi show, his style has moved on and transposing these structures on to landscape brings a much-needed narrative aspect to his painting. The Mondrianesque grids become a lens, rather than the image itself, and the formal rigidity of this foreground creates a rhythm in the work that leads us through what’s taking place in the street.

The style works differently but well in one of Ouadahi's interior paintings, also included in Breathing Space. We see a labyrinthine underground passage, tiled in mucky white porcelain. It suggests a subway, yet in the sharp turn at the end of the corridor there is a sense of foreboding. The intense, brutal repetition of lines appears sinister and the work asks who or what is around that corner?

There’s a sense of decay in the tones used to render this scene, which is only heightened by the inappropriately clinical white tiles. Parallels are clearly to be made with the monotony of the urban scenes elsewhere in the show.

But compared with these two series, the painstakingly realistic images of barbed-wire fences – however impressive and clearly taxing their creation might be – don’t quite have the same oomph. The freedom suggested in their torn apart surfaces is a little more direct and thus less captivating than the muted, reflected disorder found in Ouadahi’s urban landscape scenes.

Oudahi talks about these barbed-wire works as reminiscent of the repetitive geometry found in North African patterns. He says that the realism of the paintings is a way of breaking down the barrier between the painting styles he found in Europe and art from home.

This remains an outstanding show by one of the few contemporary painters coming out of Algeria. Breathing Space demonstrates Ouadahi's clear sense of direction, and his breakthrough in this otherwise confined and boxy world.

Breathing Space continues until March 14 at Lawrie Shabibi, Al Quoz, Dubai

[ clord@thenational.ae ]