It has been a few months since news of an economic meltdown hit, yet at Etemad Gallery in northern Tehran, there is little evidence of the grey clouds which loom over markets elsewhere. We're in a bright-white room filled with canvasses by a young Iranian painter, one of the many represented by the gallerist Amir-Hosein Etemad. Colourful works overwhelm the walls and new pieces are being carted in for a next exhibition; the phone constantly rings. Business looks good."I'm very happy about the market at the moment," says Etemad, who has owned the space for five years.

Etemad has managed to circumvent the financial hit that many of the world's art markets have taken, particularly within the contemporary art scene. During art auctions last November, which have acted as a benchmark for setting prices well into the new year, Sotheby's, Christie's and Phillips de Pury all sold less than their pre-sale estimates, according to an October Forbes article, with Sotheby's stock down 83 per cent from its previous price in October of 2007. Russia and the Middle East, which were two of the engines which drove the global market, have also begun to cool, with Sotheby's November figures of Russian art dipping below its low estimate, according to Bloomberg.

Yet oddly, Iran has remained somewhat sheltered from the financial storm. Etemad and other gallery owners in Tehran are experiencing a curious after-effect of the global recession: that interest in the domestic Iranian art market is going up as prices drop to more realistic levels. "I'm relieved that the recession stopped the bubble," he enthuses. "Now, prices are finally going back to normal." The bubble began to grow in Dubai about three years ago as an abundance of young buyers, particularly in the financial sector, channelled their excess income into Middle Eastern and Iranian art, fuelling speculation that drove prices through the roof.

"When I did my first show five years ago, I didn't sell a thing," says Isabelle van den Eynde, the owner of B21 Gallery in Dubai." Frequently travelling to Iran in order to find artists, hers was one of the first to promote Iranian artists in Dubai. "Now," she says, "people are fighting to buy these pieces." Prices leapt over the course of a few years and relatively unknown, but experienced artists like Shirin Neshat, Parviz Tanavoli and Charles Hossein Zenderoudi, who had been producing art since the 1970s, found sudden commercial success on the world stage by using Dubai as a platform. Zenderoudi's Untitled sold for $13,200 (Dh48,444) at Christie's 2006 auction in May, while two years later, another work also named Untitled was sold for $97,000 (Dh355,900) at Christie's April sale. Other pieces also sold well above expectations: Neshat's I Am Its Secret, sold for $48,000 (Dh17,616) at the Christie's 2006 auction, while another one of her pieces, Whispers, sold for $265,000 (Dh972,000) in 2008.

The Financial Times noted that in the annual trend art market research index produced by Hiscox, the art insurer, the value of contemporary art has risen by 55 per cent over the past 12 months, which is an acceleration of a gradual five-year rise that has seen prices soar. The market correction, when it came, was dramatic, but to some, a relief. "The market was a bit too ridiculous," says Maliha al Tabari, the owner of Artspace Gallery in Dubai. "It just went too extreme. At this point right now, the market crash is a wake-up call for everybody. Prices will stabilise and become more realistic."

Now that collectors are less willing to splash out, many are travelling to Iran in search of bargains. "There are a lot of new collectors coming," says Etemad. "London, Switzerland, Dubai, France - even from Beijing and New Zealand. This is new. This has never happened before." Why the big interest? "It's cheaper," he says matter-of-factly, and interest is still high. "We have always been selling at normal prices, and I'm glad the market reflects that now. People are seeing that they can come here to invest in good art. Before, it was speculation, and people were paying millions for work. Now, because art is sold in a more acceptable range, it is affordable for more collectors."

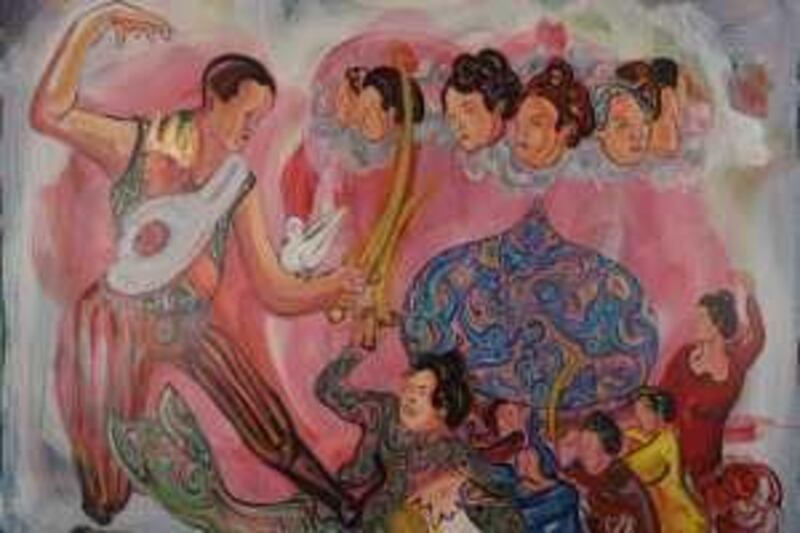

Ramtin Zad, a 24-year-old painter from Tehran, has recently finished exhibiting his work in Etemad's gallery. They are taking down his large canvasses as we enter the gallery. Bold, colourful and humorous, his figurative paintings are a fraction of the cost of the Iranian art on sale in galleries abroad. Most of the pieces in the gallery measure over a metre in length, and they sell for about $2,500 (Dh9,175) - a price befitting of an emerging young artist.

Ferial Salahshour, the owner of Day Art Gallery in Tehran, also expresses relief that the market has corrected itself. "We have not been so affected inside the country by the crisis," she says. "But prices did come down a little bit, and it is good, especially for young artists. I think that they must be humble and think about their work instead of thinking about high prices." Salahshour, an avid collector of both contemporary and Iranian art for 35 years, emphasises that for the artists she represents, gaining exposure is more important selling at high prices. "I tell them it is so important to be seen, to be sold. This way your work circulates and can be discussed." While works such as those of Ebrahim Haghighi, a well-known graphic designer in Iran she recently exhibited, are in the pricier range, she says that for a young artist that wants their art to be visible, $500 (Dh1,835) is a reasonable asking price. "It's not expensive at all," she adds.

Charles Pocock, who is an adviser to the Abu Dhabi Music and Arts Foundation and is also the managing partner at Dubai's Meem Gallery, believes that the newness of Dubai's art market initially caused a lot of buzz and excitement that, when combined with the abundance of wealth in the region, sparked hyperinflation. "Some people take auctions seriously because it is thought that buying art is a socially acceptable and a high-end activity. However, without a proper knowledge of the market, the effects can be devastating."

Pocock also thinks that the art bubble had largely to do with inexperienced collectors who viewed art purely as an investment. "When art starts to become an investment only, it's the writing on the wall. People buy art, they flip it, and it creates a cyclical rise in prices that does not necessarily reflect the value of the art." As eyes turned towards Iranian art, the effect was not only an increase in sales, but a galvanisation of the Iranian aesthetic. Once artists realised that certain recognisably Iranian motifs, such as calligraphy, were selling well, many shifted the focus of the painting to accommodate this trend.