As a teenager, Joan Miró, who would go on to be one of the 20th century’s most important artists, used to go to the beach near his house at night and spend hours staring up at the sky. According to neighbours, he was once arrested by the police, who thought he was waiting for smugglers. Locals had to intervene and tell the officers the boy wasn’t a criminal, just “a little bit crazy”.

The side of Miró that was a dreamy, stargazing boy can be discerned in Joan Miró: The Ladder of Escape, a landmark exhibition that opened last week at London’s Tate Modern. The show is named after one of the paintings on display there, depicting a ladder in black, blue and red stretching up to a sketchy moon. A human form with wires for hairs and lines for fingers stands looking up at it, mouth open, while stars and geometric shapes float in a blotchy sky.

The image of a ladder recurs over and over again in the work on display. There's a ladder in his early, realist masterpiece The Farm, which was painted in 1921 and was once owned by Ernest Hemingway, and there's one in the more surreal sculpture The Ladder of the Escaping Eye, which has a ladder stretching up from a piece of lumpy stone to a disembodied eye and was painted 50 years later. The exhibition's co-curator, Matthew Gale, says that the show's title was picked because it refers both to "the connection between the earth and the sky in [Miró's] paintings and sculptures" and to "the ambiguity that he has in relation to events around him". Miró, who was born in Barcelona and fled to Paris during the Spanish Civil War, was often motivated as an artist by political events. In Gale's words: "He wants to escape [from reality], but he can't. The ladder has to rest on the ground."

Politics isn’t the first thing most people associate with Miró, the Catalan painter who helped kick-start surrealism and influenced painters as different as Salvador Dalí and Jackson Pollock. “In most exhibitions there is the image of Joan Miró as a childish, trivial artist who paints suns and moons and stars in bright colours,” Miró’s grandson, Joan Punyet Miró, said in a speech at the London show’s launch, in which he praised its focus and depth.

“My grandfather was a man who really brought a revolution,” he went on. “Picasso was fighting for freedom in France, my grandfather in Catalonia. The accent on this political reading, for me, is making this exhibition the most important exhibition I have seen so far of my grandfather’s.”

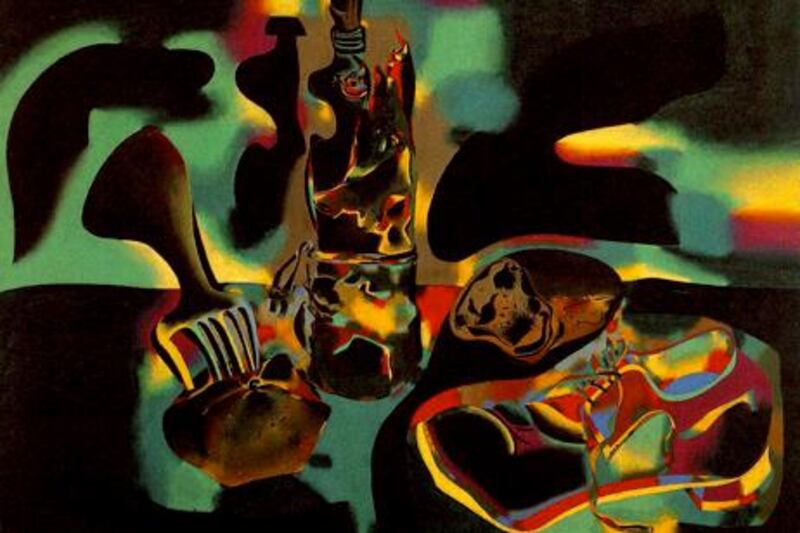

Of the 150 artworks on display, spanning six decades, many were painted during either the Spanish Civil War or the Second World War and are full of grotesque human figures with spiky teeth and misshapen bodies. A poster Miró designed, emblazoned with the words "Aidez L'Espagne" is on show next to an image of the lost artwork The Reaper, which was commissioned along with Picasso's Guernica for the Spanish Pavilion at the 1937 Paris Exposition Internationale. The "Barcelona Series" of prints, produced in 1944, is full of menacing monsters and terrified victims.

These small, busy, anxious pictures are displayed close up against each other, and are overwhelming to the eye. It’s a relief to move on to rooms devoted to Miró’s gigantic, abstract triptychs, made after the painter had embraced Zen Buddhism, visited New York and seen shows by abstract expressionists such as Pollock (who, in turn, had been influenced by seeing Miró’s earlier work).

Dominating the anterooms, these abstracts encourage meditative reflection. The details of earlier work have been stripped away, leaving the bare bones of painting: a line, a splodge of primary colour or background wash, some dots. Most recognisable among these are Blue I, II and III, painted in 1961 and now on loan from the Centre Pompidou in Paris. All three have the same cobalt background, punctuated only by black spots and vivid red gashes.

According to the co-curator Marko Daniel, the colour was chosen by Miró because it’s the part of the spectrum that humans can see in the least amount of detail: as viewers we become lost in it; it puts us in a trance. The paintings, which can be underwhelming in reproductions, are mesmerising when they fill your field of vision.

The Miró quote that gets repeated most often is his vow to "destroy everything that exists in painting" (despite the fact that he remained a painter throughout his incredibly productive six-decade career.) The boldest of his large-scale abstract triptychs, Painting on White Background for the Cell of a Recluse (1968), is also the one that strips most away from what's expected of a painting.

Each panel is white, with a thin, wobbly black line tracing a path from somewhere near the bottom left-hand corner upwards and to the right. That’s it; but the paintings somehow have depth and force.

Challenging and filled with political verve into his 80s, Miró didn't soften in old age, even if the later abstracts seem more serene than earlier work. The Hope of a Condemned Man, another triptych that was borrowed from the Joan Miró Foundation in Barcelona, was inspired by a garrotted prisoner, and his Burnt Canvas series, for which Miró attacked and set fire to canvases, shows he still had plenty of anger and anxiety to channel into his work.

It’s the juxtaposition of this fire with Miró’s more philosophical sense of wonder that’s captured by this invigorating exhibition, and both are reflected in the show’s title. When the Spanish Civil War broke out, Miró said, he “felt a deep desire to escape” and “the night, music and the stars began to play a major role in suggesting my paintings.” But the work on show demonstrates that he was never able to escape completely from reality.

Follow us on Twitter and keep up to date with the latest in arts and lifestyle news at twitter.com/LifeNationalUAE