A river of what appears to be oil and blood cascades down a cast-iron staircase. A swarm of plastic dragonflies homes in on a neon model of the World Trade Centre. Junk-shop ornaments are arranged into mysterious structures. A scrambled, seething series of images plays on a group of monitors. The stills on the walls are no easier to parse - a toy robot, plastic fangs, a water sprinkler on a lawn. "The aesthetic comes from the city, in a surreal way," says Mamali Shahafi, the curator of and contributor to IU Heart, the Third Line gallery 's all-Iranian summer show. "If you have a big quantity of ugly and trashy things together, it makes something extraordinary. That's why I like living in Tehran." I laugh politely. Shahafi doesn't.

"For me, everything is horrible in Tehran," he says. "But when you have more than three or four elements every day where a horrible thing happens, you think, oh wow, this is really great, actually, because it's something unique, something original." Whether or not it's unique or original, IU Heart is certainly very striking, and very thoroughly Iranian. Shahafi, a young artist trained in Tehran and Paris, contributed the videos. The iron stairs (titled Mother of Nation) are by Mahmoud Bakshi, a Tehrani who recently exhibited at the Saatchi Gallery.

"This stair could be the stair of the mullah going up to give you a lecture, and also the stair of the plane Khomeini comes down," says Shahafi. "This aesthetic of the stair reminds us of lots of different religious elements." The towers are by Shahab Fotouhi. Vahid Sharifian, one of the stars of the recent Iranian show at the Farjam Collection, contributed the strange ornamental works. The stills are from Arash Hanei, sampled from earlier, more lucid series and jumbled up because, as he apparently told Shahafi: "In this moment I don't want to say anything serious, and I find if I mix the things together nobody can understand the message."

The show, or a version of it, was originally intended to take place in the Iranian capital, a celebration of Tehran's rising generation of artists, the children of the 1979 revolution. But, wouldn't you know it, something horrible happened. The government, always nervous around cultural activities, blocked the exhibition shortly before its scheduled opening. "It was right before the election," Shahafi sighs. "We were all kind of confused, and we were going to cancel this show. We were already thinking what we could do because we could not have permission in Tehran. Then the election happened, and for two or three months we were all really busy."

More than a year on, an adapted version of the show has finally found an audience. The original plan had been to present the distinctive sensibility of Shahafi's own artistic peers. Yet political circumstances suggested that something more pointed was called for, however oblique that may be. "My problem was that most curators who work with Iranian artists, they don't try any theme or any subject," he recalls. They prefer, in his experience, to show off their local discoveries.

"Let's say I find this old lady, I find this young guy doing graphics. You want to show them all together because you found them," Shahafi says sourly. He decided he could do better himself and put together a show that was unified by a generational outlook and a "special relationship", so to speak, with America. The five artists gathered in IU Heart were all born between 1977 and 1982. "All of us had our childhoods during the war," says Shahafi.

"After, when we were teenagers, it was during the Khatami period when we had some more freedom to talk and for ideas. After that, when we started mostly as artists, it was when Ahmadinejad started." Along with the same set of historical reference points, they also share a certain ambiguous sensibility - disaffected, weary of politics and yet compelled to address their times, drawn to fantasy yet conscious of its inadequacy.

Of the first draft of the show, Shahafi remarks: "I found the art was completely like a fun-fair. That was an interesting point for me, because that was the feeling of the young generation. They were avoiding this politics stuff. They wanted to basically just live in a world that they had created and just replace it with more colour, light, alive things." Neon crops up often - "a really American element", says Shahafi.

All the same, there was, he says, "something not completely joyful", even "deeply sad", about the work. Vahid Sharifian, for instance, retreats into a world of retro kitsch, of sculptures and tableaux assembled from gleefully saccharine mass-market ornaments. "When you go to his studio you have a feeling you are in the 1970s, kind of a New York flat," says Shahafi. "Everything, old LPs, Elvis Presley ... He's really in this universe, you know?"

In his personal statement for the show, Sharifian imagines a sardonic dialogue between himself and an uncomprehending questioner. "I say: Iranian politics has nothing to do with my life," he writes. "They say: 'How is that possible? Don't you live in Iran?' I say: 'No, I live in my own house'." But he also lives in Iran, of course. One reason he could not come to the Third Line opening was, Shahafi says, that "he cannot come out of the country because he did not do his military service." Even so, "he's always also having this American dream".

The theme of engagement with America emerged organically as the show was coming together. "I started the studio visits to select the artwork," Shahafi explains, "and just accidentally I found that the artists, now I'd selected them, they all had in their work something about the US, and international politics in general. And that was really interesting for me because I never thought all these artists had some work about the subject."

However, following the contested Iranian election and the violence that attended it, Shahafi decided that the work he had selected was no longer equal to the moment. "I wasn't happy any more with the subject," he explains. "For me, this show was showing a reaction, a social, political reaction, of this young generation. But this election was a big shock. Then I didn't want to show again the same artwork."

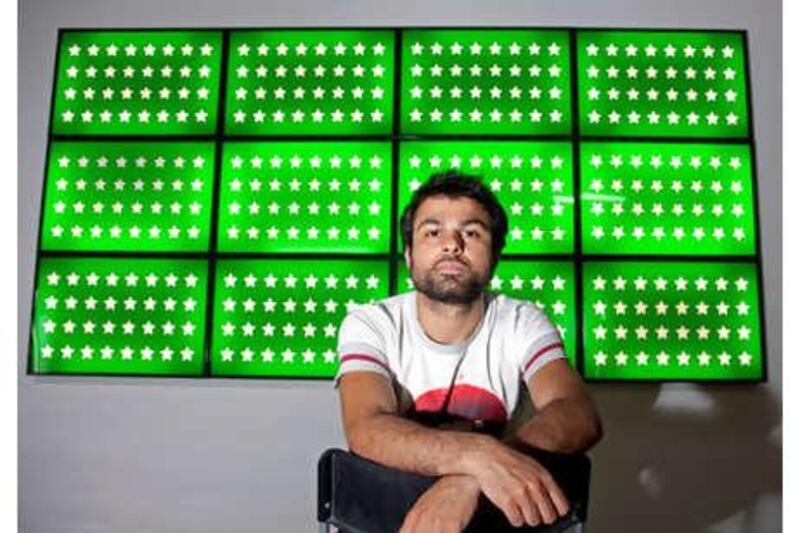

He invited his artists to submit alternative pieces. He also added a new piece of his own, titled IU Heart: a wall of light-boxes displaying the stars of the American flag against a green background. "Green in Islam is a very symbolic colour", he says carefully. "The meaning of green changed in Iran a lot, and people can look at it also as like the Green Movement. This is the interesting thing about political work. It could change easily by day with the political situation."

Despite the ambivalence of his peers, Shahafi wants his work to address the world as it is now. "You cannot always be thinking, okay, I'm doing art and I want to keep it in art history," he says. Admittedly, the price may be that he will be "completely forgotten" in a generation. "Lots of people think this is the bad thing about political work," he admits, "but I think it's always important to make something for the time." What else is there to say, except: catch the show now.