Creating a repository around a novel seems rather hubristic and pedantic at first, until you visit Turkish author Orhan Pamuk's Museum of Innocence in Istanbul and realise that it's as much about the visitors' interpretation of objects as the book itself.

Entering Orhan Pamuk’s newly opened Museum of Innocence, I felt like my grandmother must have done when, at age 82, she was asked to try sushi. I knew, or thought I knew, what went into the stuff. I knew to try to keep any preconceived notions at bay. And finally, despite being told I would like it, I knew fully well I would not.

Firstly, there was the pretense of it all. I had heard, here and there, of writers who had fought tooth and nail to have their books made into movies, but whoever heard of a novelist, even a Nobel laureate as it were, building his book into a museum? In Pamuk’s case, the museum, like his eponymous book, was set in Istanbul. This invited another uncomfortable question: exactly whose Istanbul would find its way into the project? The author’s, or that of the city’s 15 million less notable citizens?

Pamuk, to his credit, had reportedly come up with the idea for the museum first and the book second. Inevitably, the two became inseparable: the book took on the shape of an art catalogue with a plot. Fine, I had figured, if not of hubris, then Pamuk was surely guilty of pedantry. To have come up with the idea for a museum after writing the book, and to have delegated the task of designing and stocking it to someone else, would have left some room for artistic interpretation. But to have worked on both the book and the museum in tandem, and to have nearly monopolised artistic direction over the latter, risked transforming a captivating, original enterprise into something very prosaic. That, I think, was exactly what an acquaintance who participated in the early stages of the project had feared when he told me: “Here, there will be no room for interpretation, only illustration.”

Then there was the novel itself. Painstakingly crafted, brainy, delightfully complex, few of Pamuk's books are a light read, and Museum of Innocence is no exception. Not because it is as esoteric as My Name is Red or as introspective, as only Pamuk's biography of a city could be, as Istanbul: Memories and the City, but because the distance it creates between its fictional characters and its reader is, at times, difficult to bridge.

In Istanbul, Pamuk, trying to capture the spirit of his home city, writes of huzun, Turkish for melancholy, a word that contains overtones of unrelenting despair. Turks coming of age in a city whose energy is at times hypnotising and at times hard to bear may bridle at Pamuk's portrayal of Istanbul as an old, crumbling mansion. Even they will admit, however, that beyond the souvenir shops of Sultanahmet, the shopping malls, throughways and housing projects built on top of centuries-old neighbourhoods, the art galleries, boutiques and clubs sprouting up around Taksim, huzun endures – and, as a word, captures the Istanbul experience better than most.

The thing about huzun, however, is that it is easier to appreciate in a place than in a person. In the abstract, or in the inanimate, huzun is enchanting; in the flesh, it is tiresome. That, at least, is the lesson of Museum of Innocence, where huzun finds its personification in Kemal, the book's lovesick protagonist.

Because Kemal cuts such a pathetic figure – a hopeless romantic starved of romance minus the romantic – engaging with him as a character, not to say sympathising with him, is a tall order. “In a country where men and women can’t be together socially, where they can’t see each other or even have a conversation, there’s no such thing as love,” his mother tells him, exasperated with her son’s fruitless pursuit of Fusun, a comely shopgirl-turned-actress. You would expect your own romantic soul to rebel against such a statement. The reason why it does not, and why you often find yourself siding not with Kemal but with a society that thinks him a fool, is that his affection for Fusun is much closer to infatuation than it is to love. Infatuation, of course, is understandable. But that it should last eight years and several dozen chapters, and that its object should be so two-dimensionally drawn – Fusun’s beauty is her most manifest quality – strains both patience and credulity.

Frustrated lovers seek consolation in an infinite number of ways – in friends, family, books, hobbies or, if all else fails, booze. Kemal, even if he doesn’t shy from the latter, finds the ultimate relief for his love pains in hoarding all manner of objects that remind him of Fusun. A single visit to his beloved’s old flat, for example, sees him walk off with a piece of wallpaper, a door handle, the handle of the toilet chain, a few hairpins, a large mica marble and “the arm of a baby doll”. Three paragraphs later – in what will surely make for a memorable scene, though possibly for all the wrong reasons, if Pamuk’s book ever earns a film adaptation – we find Kemal rolling around in bed with the day’s catch.

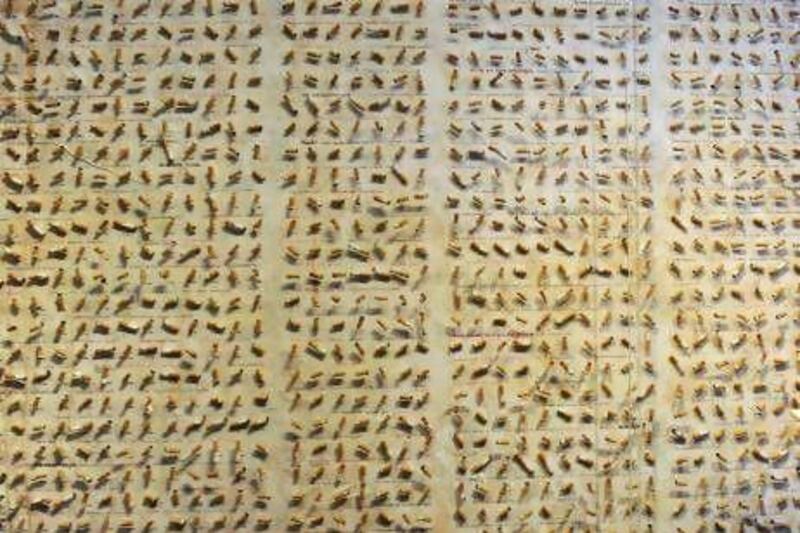

"Sure enough," he tells us, "these things that Fusun had touched, these objects that made her who she was – as I caressed them, and gazed at them, and stroked them against my shoulders, my bare chest and my abdomen – released their analgesic and soothed my soul." Among the long list of Fusun-related mementos that Kemal lovingly stockpiles over the years, one stands out from the rest: his collection of 4,213 of Fusun's cigarette butts, accumulated during years of visits to her family home. "Each one of these had touched her rosy lips and entered her mouth, some even touching her tongue and becoming moist, as I would discover when I put my finger on the filter soon after she had stubbed the cigarette out," Pamuk's protagonist writes. "The stubs, reddened by her lovely lipstick, bore the unique impress of her lips at some moment whose memory was laden with anguish or bliss, making these stubs artifacts of singular intimacy."

In Pamuk’s museum, located, like Fusun’s house, in Cukurcuma – one of an increasing number of Istanbul neighbourhoods where huzun seekers are as likely to stumble across a street vendor pushing his rackety, fruit-laden past an old, crooked building as an estate agent is selling said building to a foreign investor – the cigarette butts are the very first thing on display. In the book, they are a symbol of Kemal’s doggedness and the depth of his attachment. In the museum, they are a showstopper.

Attached to a large canvas by means of small, nearly invisible pins, each of the 4,213 cigarettes is dated, the earliest from 1976, the last from 1984, and faintly smudged with traces of Fusun's red lipstick. Exacting as a writer, Pamuk was doubly that as a curator. As Elif Batuman found, writing in The New York Review of Books, Pamuk acquired the desired effect by having his assistants feed thousands of lit Samsuns, Fusun's brand of choice, into a vacuum machine.

To complete the process, the artist who designed the panel was asked to press the remaining filters to her lips. “She also had to redo 600 or 700 cigarettes,” Batuman wrote, “because Pamuk said she was wearing too much lipstick, much more than Fusun.” Many of the butts are accompanied by a brief hand-written caption recalling the moment Fusun had smoked them. The writing is Pamuk’s. Often, the caption is a quote.

The effect is mesmerising. To a reader-cum-visitor blessed with above average powers of retention, a stub bent out of shape and accompanied by the words “I forgot the beginning of the film” might recall something that Fusun said, or did, in one part or another of Pamuk’s novel. To someone who does not remember, however, or who has not read the book, each of the stubs takes on a life of its own.

It was Hemingway who, asked to compose a novel in six words, allegedly penned the words: “For sale: baby shoes, never worn.” None of Pamuk’s short captions might pack quite the same punch but many do resonate with a meaning, or a mood, that goes well beyond the confines of his novel. “Let this be the last one Kemal,” says one, next to a stub dated September 16, 1983. “Of course, beauty isn’t everything,” reads another, or “don’t be angry with me my pretty, don’t ever be angry with me”. Each cigarette has its place in the book, but each also invites us to write it a new story, a new context – who smoked it, where and why – from scratch. Slowly, the question raised earlier – whether the museum is meant to be Pamuk’s, or Kemal and Fusun’s, or yours and mine – becomes redundant. Extracted from Pamuk’s world, the stubs enter another one, or find a place in our own.

The cigarettes set the stage for the rest of the exhibit, which comprises a total of 83 small glass display cases, each of which takes its name and inspiration from a chapter of Pamuk’s book. Chapter 49, entitled “I was going to ask her to marry me,” features a mirror suspended above a rusty bathroom sink, complete with a shaving kit, soap and, tellingly, a tube of lipstick. “Love at the Office” stars an ashtray with two cigarette butts and a tulip-shaped tea glass against the background of workers’ IDs from the 1970s. Some of the representations are literal, like “The Feast of the Sacrifice,” which features an old knife used to slit animals’ throats. (What Pamuk asked his assistants to do with the blade to attain the desired effect, I am afraid to ask). Some are more contemplative, like “Jealousy”, where a velvet curtain partially obscures the drawing of a light shining inside a single room on an otherwise dark, empty street.

One of the most poignant – and political – contains a small flat screen receiving a stream of headshots of women with thick, dark bands drawn over their eyes. The photographs change, but the dark bands remain. It is fitting allusion to “A Few Unpalatable Anthropological Truths”, a chapter that speaks of the consequences some Turkish girls had to face in the 1970s if they lost their virginity before marriage. “In those days it was the custom for newspapers to run the photographs with black bands over the ‘violated’ girls’ eyes, to spare them being identified in this shameful situation,” writes Pamuk. “Because the press used the same device in photographs of adulteresses, rape victims and prostitutes, there were so many photographs of women with black bands over their eyes that to read a Turkish newspaper in those days was like wandering through a masquerade.”

The rest of the exhibit is a bit like your old uncle’s attic, except re-arranged by a taxonomist – display cases full of scissors, hairpins, newspaper clippings, black and white photos, clocks and watches, matchbooks, an old driving license. Objects that would have found their way to a garage sale find their way to a museum instead. There isn’t irony in this, or affectation. Unlike Duchamp, who would exhibit a urinal to challenge, or mock, a museumgoer’s notion of art, Pamuk doesn’t pretend that an old ashtray is anything other than what it is. His aim, in casting it as part of his museum’s collection, isn’t to establish it as a work of art but to restore its dignity as an object, and our emotional relationship to it. The fact that it is supposed to be Fusun’s, and that all of the items on display are supposed to enjoy some link to Pamuk’s book, becomes, at some point, an afterthought. The museum doesn’t ask us to celebrate everyday items such as ashtrays, hairpins or salt-shakers as part of Fusun’s story, but of ours.

Perhaps this is exactly what Kemal, whom Pamuk credits with the idea for the museum at the end of his book, had in mind. "With my museum," he says, speaking to Pamuk, "I want to teach not just the Turkish people but all the people of the world to take pride in the lives they live." Were he to eavesdrop, as I did, on a middle-aged woman and her teenage daughter who had stopped next to a display case containing an old bottle of Meltem fruit soda, a fictional drink, Kemal would have been happy to hear the woman

reminiscing not about the bottle's relation to Pamuk's book but about the sodas she herself would drink as a child.

I wasn’t sure if the thrill of visiting Pamuk’s museum would tempt me to revisit his novel. Having to endure Kemal for 600 pages, I still maintain, is harder, and less gratifying, than relating to the objects he hoards.

Of course, having been dead wrong to assume that Pamuk’s exhibit would be nothing more than a shrine to his book, I might also have been wrong about his protagonist. As a young woman I met on the last floor of the museum told me, a copy of Museum of Innocence pressed to her chest (she’d read it twice), there was something very believable, very Turkish, about characters like Kemal.

She knew what she was talking about, I suppose. She had her own collections, she said – of movie tickets, theatre passes, and the like. By the time she confessed to stowing away her ex-boyfriends’ toothbrushes I had decided to give the book another try.

Piotr Zalewski is a freelance writer living in Istanbul.