In the wood-panelled formality of the Trustees Room of the New York Public Library an intense, rather nervous, woman is holding an audience in rapt silence.

In gentle cadences, the Lebanese playwright Maya Zbib is performing her one-woman show, The Music Box. There is a lightness to her voice that contrasts with the shelves of portentous books and elaborate tapestries that stuff the room, but it is a lightness that is deceptive because her story tells of life in Beirut - a world of violence to women, disappointed marriages, mislaid dreams and untimely death.

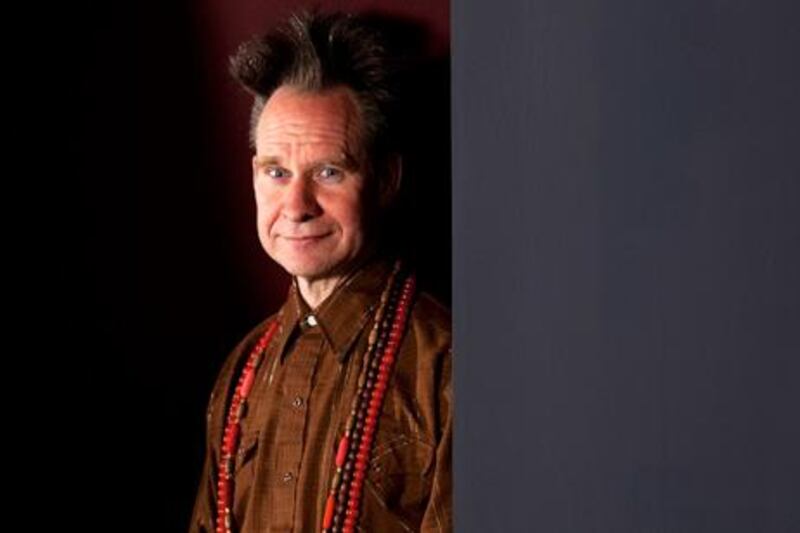

She is so affecting that when the short performance ends there is a silence, then heartfelt applause and even tears. And few shed more than the charismatic American theatre, opera and festival director Peter Sellars, who is sitting in the front row.

"I was crying my eyes out," he says. "I knew the text but this is the first time I have seen Maya perform. So much in the Middle East comes from a sense of desperation, so it is beautiful to see something of intelligence, of balance, of quiet and understanding that comes from an inner clarity."

Why does this matter to Sellars, who has gained renown worldwide for his transformative interpretations of artistic masterpieces, who is more at home in the opera houses of Chicago, Glyndebourne or Paris than he is in Lebanon? What is this unknown performer to him?

He and Zbib were thrown together by the Rolex Mentor and Protégé Arts Initiative, a biennial scheme that was launched in 2002 and for the past year has paired a young artist from South Africa with the sculptor Anish Kapoor, an Australian musician with the ambient music composer and producer Brian Eno and a Palestinian filmmaker with the great Chinese director Zhang Yimou.

The idea is that they work, talk and investigate their art forms together but do not necessarily come to any particular conclusion or complete a piece of work.

Indeed, as Sellars says: "Maya made this before she ever met me, so I take no credit of any kind. We really concentrated on life questions and things we cared about but never discussed her art. There were no conversations about stagecraft - none at all. She saw me rehearse, but I never saw her make anything."

Born in 1981 during the Lebanese civil war, Zbib studied at Goldsmiths in London and was one of the founders of Beirut's Zoukak Theatre Company, a collective of six former Beirut University students, which works with victims of domestic abuse and children damaged physically and mentally by the struggle to survive in the war-ravaged refugee camps of south Lebanon.

She normally performs The Music Box in other people's houses with an audience of 30 or so and uses boxes as props to represent memories and secrets with contents that include the random ephemera of everyday life - a length of string, a letter, photographs. She uses the refrain: "A house begins with ... a key; a bed; slippers; the dining room ..." to draw the audience into a series of intimate accounts that examine the emotional ties that women have with their homes and family.

"Meeting Peter pushed me to look for what the performance is really about," says Zbib, whose nervousness was caused by acting in English for the first time. "Things that I was saying became more meaningful because I was thinking about them in a different way. There were certain nuances I didn't understand until the actual performance because, in a very quiet way, he helped me to see things differently."

If Sellars has galvanised her work, he seems to have gained as much as her by his visits to Lebanon.

"I learnt much more than Maya," he says. "When we were together we developed a very emotional and very powerful friendship and she showed me things that I had never seen in my life. I thought I understood what Arab artists were doing - I have worked with the great Lebanese writer Amin Maalouf over 15 years, staging works as poetic images - but being in Beirut with her was overwhelming because I realised I had no idea of the reality."

For Zbib, reality is developing drama therapies that she and the collective can use in different locations.

"It's not just children in the Palestinian camps - right now we are creating a production with a group of women who have been subject to domestic violence. We do not have a law against it. If your husband hits you, a woman has to go to the sheikh or the priest who will deal with it. If you go to the police they will say: 'It's not a problem - go home.' It is very difficult for us to work together because they don't want to be seen so they come secretly to rehearse without telling anyone."

Sellars chimes in: "In community situations, Maya is very empowering because she is giving people permission to go to a place where they would not allow themselves to go. She has this way of disarming people and making them feel everything will be totally fine. She doesn't tell them to relax, she relaxes everyone. There are no strident theatricals."

But in her quiet way Zbib is undoubtedly fiercely committed to her causes.

"My work is political for me, but we don't do it like it's CNN," she says. "Many people address politics as if they are presenting the news and I don't want to do that. I want to do what is personal, what really touches these people. I like to leave them the space to imagine and think and not just give all the information. I don't say: 'This is my country and it's not good and it's all your fault.'"

Although a performance of The Music Box on YouTube is more theatrical - and perhaps more overtly political - than the debut in the New York Library, the group has not run foul of the authorities. And that, surprisingly, is a problem.

"It's as if they don't see us," says Zbib. "There is a lot of censorship in the country but not against us because they don't understand the lines. They don't see us as a threat, so they don't listen and that's something we should work on."

As someone constantly challenging the status quo, Sellars invited Zbib to attend rehearsals of his controversial production of Handel's opera Hercules this year in which the hero was re-imagined as an American general returning from Afghanistan. He further challenged her by taking her to war-ravaged Democratic Republic of Congo to meet Faustin Linyekula, a dancer and choreographer. Millions were killed in the DRC's latest bout of civil strife, which officially ended in 2003 and the graves of the dead still line the river.

Zbib recalls: "It was very intense for me. I could smell the violence in the woods and the houses and on the river bank.

"It was the only time that I have felt scared to go out alone. Normally, I don't care. I go out everywhere. But I was one of the few white people and I could feel the violence. I had to go back to the house in a compound where we were staying.

"But there we were living behind the bars of our porch - like we were in a cage. These beautiful black women used to come into the yard for water and we would watch them from behind our bars and they would watch us. It was really startling.

"It moved me and will stay with me forever. Now I understand there are worse places than Beirut."