Sounds, not sights, are the first thing that greet you as you enter the darkened galleries on the first floor of Modern Art Oxford: the plaintive strumming of an oud, the reedy voice of a young boy reciting the lyrics of an Egyptian love song, the voice of an older male singing the signature tune from Ali Edries' 2001 movie, Ashab Wala Business (Friendship or Business).

The effect is not just to transport you from the chilly pavements of Britain's oldest university town to some indeterminate location in the Middle East, but also back in time to a series of specific moments in Palestine, Lebanon, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Libya, Yemen and the UAE, each of which have been captured in a still or moving image and represented as part of The Script.

Works from the Lebanese artist Akram Zaatari

A travelling exhibition, The Script opened last summer at New Art Exchange in Nottingham, which commissioned the new work that provides the show with its name, but Modern Art Oxford's exhibition is the third, final and largest iteration of it featuring five major installations by renowned Lebanese artist Akram Zaatari.

The first work in the exhibition not only acts as an introduction to Zaatari's ongoing concern with how people imagine themselves through pictures, but also references the original Nottingham show and Zaatari's role as one of the founders of Beirut's Arab Image Foundation.

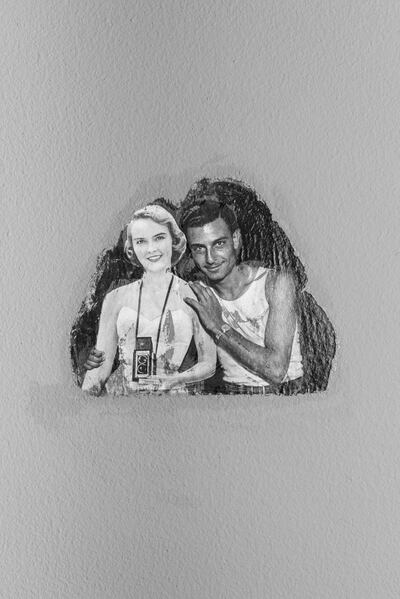

Footnote to Hashem al Madani: Studio Practises (2018) features a series of 14 portraits from the Studio Shehrazade archive, a commercial photographic business that operated in Zaatari's home town, Saida, between 1953 and 2017. Rather than being exhibited in frames, the images were originally transferred onto the walls of New Art Exchange and have subsequently been chipped out of its walls and transferred as fragments to Modern Art Oxford, complete with pieces of the original masonry.

Revealing broader cultural patterns and ideas

Zaatari sees the fragments as remains, almost as pieces of fresco, which are now recessed into a wall at Modern Art Oxford, like a series of fossil-bearing rocks that have been split to reveal the secrets of their innards. “A picture is always a negotiation between the photographer and the subject’s desire, and so these are performed images and I wanted to stress them not as part of photography’s history, but as the attitudes of the people posing,” says the 63-year-old artist, who often refers to his work with the archives created as part of the Arab Image Foundation as a form of archaeology.

“At the end of the show at New Art Exchange we decided we would do all that was possible to preserve those images, but as remains from a show that was performed only once, so they become like traces, a reminder.”

Zaatari approaches apparently disparate collections of images in the same way that an archaeologist might approach a spoil heap, not to establish their photographic or art historical credentials, but for their ability to reveal broader cultural patterns and ideas.

'Dance To The End of Love'

The practice informs Dance To The End of Love (2011), Zaatari's 22-minute-long, four channel video projection. Its edited visuals and music transform the upper gallery at Modern Art Oxford into something akin to the dance floor of a nightclub.

Composed of video footage from across the Arab world that was uploaded on to YouTube on the eve of the Arab uprisings, Zaatari describes the work as "a capture of the social attitudes of a society through what it decided to upload at a very specific time".

A window into the collective imagination of the young Arab men involved and a study in a solitude that is only momentarily assuaged by their impulse to self-promote, the footage was discovered by Zaatari using Arabic search terms derived from his work on the Studio Shehrazade archive. As well as clips of young men performing bodybuilding displays, the work features boys singing, dancing and engaging highly dangerous tricks on motorcycles and in cars.

In another section, crude special effects have been superimposed on the videos to show the young men harnessing the power of fireballs and lightning. The results are both endearing and pathetic.

"People imagine themselves as heroes when they are not, they imagine themselves as good dancers when maybe they are not; as having beautiful voices or imagining themselves as stars when they are not," Zaatari says.

"Look at how they celebrate solitude. Look at how they seek self-promotion, which I think they are taught to. We live in a society of spectacle, that wants to teach us how to promote ourselves, where it is important to have thousands of 'likes', but why is this important? It's not them, it's the world we live in that's becoming pathetic. They are victims of it and they pay with their solitude."

Inspiration for 'The Script'

It was while searching YouTube using the Arabic phrase "father and son" that Zaatari came across a genre of footage that inspired the newest work in the show, The Script (2018). It is based on uploads of Muslim men who are being disturbed by their young sons while fulfilling their duty of salah, or ritual prayer. The young boys play noisily with toys, use their fathers as climbing frames and even hang from their necks while the fathers prostrate, attempting to distract them.

Rather than using the original rushes, however, Zaatari used them as the inspiration for a filmed re-enactment, made with the highest production values. "I felt like there is something pure in that gesture of praying with your kids around you, trying to use you to climb on, that is iconic enough to become an icon," Zaatari says. "It embodies, indirectly, all of these resistances to a world that is becoming more hostile to the Muslim community."

Discussions about the work began back in 2016 at a time, explains NEA's director of programmes, Melanie Kidd, when anti-Muslim sentiment was becoming markedly more visible in the UK. "That's when we really started to talk about the commission, recent terror attacks and heightened levels of hate crime towards Muslim communities and anyone who was perceived to be Muslim," Kidd says. "We had a lot of conversations about how Muslims are perceived through the media; how they were perceived nationally [in the UK]."

An attempt to humanise Islam?

Is The Script, then, an attempt to humanise Islam for a British audience, to provide a more domestic and tender face for a faith that for some engenders anger and fear on the far right?

While admitting the context of its commissioning and its likely reception in the wake of recent anti-Muslim attacks in Britain and New Zealand, Zaatari suggests that is only partly the case. "Yes, but one could also make the work in the Christian world as well," Zaatari insists. "It has to do with dance, first and foremost, and it has to do with demystifying the time of prayer."

For Modern Art Oxford's curator, Stephanie Straine, the value of The Script lies not merely in what it says about attitudes to Islam, but in the way it reveals the broader cultural ideas that lie behind seemingly individualistic acts of self-expression. "The points Zaatari is making about the shift between public and private in our lives offers a really important moment of reflection on what it means to manufacture ones own image and how that can transcend nationality and religion or age," Straine explains.

“To consider that in a very nuanced way like Akram does is very timely.”

Akram Zaatari: The Script runs at Modern Art Oxford until May 12