Next month the landmark Palestinian Museum in Birzeit, just north of Ramallah, will mark its two-year anniversary. Back in 2016 when it opened to the public for the first time, it had no artwork or pieces to show – just its impressive architectural space and the promise of exhibitions to come. The empty space was a pronouncement of the extraordinary challenges of constructing such a building and institution in Palestine under the Israeli occupation.

Last August, as reported in Weekend, its sole exhibition space was filled with the museum's inaugural exhibition, Tahyah Al Quds ("Jerusalem Lives"), curated by Reem Fadda. Last month, the second exhibition "Labour of Love: New Approaches to Palestinian Embroidery", curated by Rachel Dedman, launched. It runs until August 25.

The exhibition provides a highly informative, accessible, unique and at times fascinating way of exploring decades of Palestinian history, from pre-Nakba to the present, through embroidery produced and worn by Palestinian women.

'The museum needs to represent all Palestinians'

A key challenge for a quasi-national institution that calls itself the Palestinian Museum is for it to be relevant and accessible to all Palestinians: those inside the West Bank, Gaza and East Jerusalem, living under Israeli occupation; the indigenous Palestinian minority inside Israel; and the millions living in the diaspora.

Each group has different travel documents and access restrictions into and within historical Palestine (ie the occupied Palestinian territory and Israel), which affect audiences and artists alike.

Someone who believes the institution has so far failed in this regard is Jack Persekian, a former director of the Palestinian Museum, who left before its opening due to differences with the board over its vision. He is one of the most respected names in the visual arts world in the Middle East.

“It’s another place, another cultural art centre. It doesn’t matter what you call it,” says Persekian, from the office of Anadiel Gallery, the first independent Palestinian gallery under Israeli occupation, which Persekian founded in 1992.

He says that when he became director, he inherited a strategy paper that clearly identified how to overcome this access issue, and that this has now been abandoned.

“The museum needs to represent all Palestinians, meaning those inside Palestine and those in the diaspora. To do that it had to create a sort of galaxy of different planets, with this main hub in Birzeit serving as a kind of the centre-of-command, while exhibitions and events would be happening wherever Palestinians are. It will mean nothing to Palestinians living in Gaza or in Lebanon or elsewhere. The idea of the galaxies, it faded – we don’t see it, we don’t hear it.”

Persekian says the Palestinian Museum is doing “more or less” what a number of other established but smaller cultural institutions in Jerusalem and the West Bank are already doing, but adds: “It’s not about real estate, the size of the building or the size of your budget, you know? It’s how relevant you are and how ...” – he pauses, searching for the right word – “how sensitive you are to what’s around you and how you can contribute to the surrounding, in terms of building knowledge, addressing certain issues, about connecting people, and doing things that – especially in the museum’s case, given the scale of it – are not possible or not within the capabilities of the institutions and organisations and museums that already exist here.”

A lack of direction and vision

One of Palestine's most respected and best known artists, Sliman Mansour, also feels that the museum lacks direction and vision. He believes an organisation of this scope should have focused on developing both a permanent collection and temporary, travelling exhibitions. It faces a challenge of reversing decades of fragmentation.

“They don’t know what to do with this building, they don’t seem to have any concept about what its function should be. Now and then they put [in] half a million dollars to make an exhibition and then it goes and the money goes.”

He adds that the turnover of directors means that implementing a vision will be extremely difficult without continuity and harmony at the top. The most recent director, Professor Mahmoud Hawari, who was on secondment from his roles at the University of Oxford and the British Museum, seems to have been forced out abruptly last month.

Zina Jardaneh, Chair of the Board at the Palestinian Museum, urges its critics to be patient. She said, by email, that the idea of having cultural centres in each key population area “remains at the core of our strategy in the long-term. In the short-term we are looking at partnerships with different museums or cultural institutions in the region and beyond, travelling exhibitions and more importantly the digital presence”.

Jardaneh points out that Dedman’s first iteration of the embroidery exhibition, called “At the Seams”, “was shown in Dar il Nimer in Beirut two years ago. This and the current, much larger project, Labour of Love, have brought original new research, new dialogue and new questions to the table, one of our main aims”.

From art of resistance to the art of subsistence?

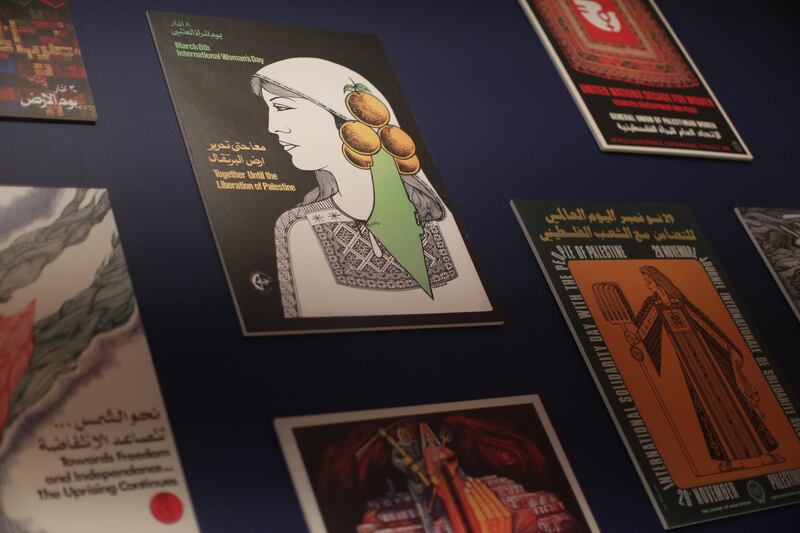

Mansour’s generation of artists played a profound role in articulating and promoting the liberation struggle through art in the 1970s and 1980s. Palestinian art and its institutions came under ruthless attack from Israeli authorities, who recognised its ability to inspire and rally Palestinians to fight for their rights and spark awareness abroad, and so outlawed it – as well as flags and even artwork incorporating the colours of the flag. Liberation-themed artwork on posters and postcards became an important way for Palestinian artists and their public to circumvent Israeli censorship.

Today, Israel has scaled back on such tactics with regard to the arts, and there are scores of museums and galleries throughout the region. What has changed presumably is the threat level to the status quo from an art perspective. A cursory look at contemporary Palestinian art suggests a preoccupation with uncertainty, or trying to make sense of a transformed landscape, with some artists, such as Larissa Sansour in A Space Exodus creating fantasies of statehood, with a female astronaut planting the Palestinian flag on the moon. The revolutionary ardour and the motherland and utopic elements of earlier regional art have been replaced in much contemporary Palestinian art by a vague, indeterminate space, a sense of limbo, with motifs of isolation, fragmentation, waiting and absence.

This affects art audiences too, which have shrunk significantly. “The occupation over many, many years tears at the very fabric of society and it eliminates any possibility for people to enjoy life, and therefore to be able to appreciate what art does for the human intellect, the human soul, the well-being of society and humanity in general,” says Persekian. “That is completely eliminated under these conditions [of occupation], and so you’re basically dealing with people operating on the level of survival mode.

Mansour believes that many Palestinians, in Ramallah particularly, have locked themselves into a neoliberal lifestyle to “escape” the seemingly interminable occupation and darkening reality over which they can exercise little control.

“People here, many of them forget that they are under occupation. Like here in Ramallah, it’s open and they can go to cafes and whatever, and they’ve forgotten all about Palestine for a while now. And banks are giving money, so they buy cars, villas and flats – all for the bank. This feeling is very depressing for people who are aware of what’s happening.”

Overcoming obstacles and imposed fragmentation

The challenges facing Palestinian artists and cultural institutions cannot be overstated. The psychological issues aside, the fragmentation makes it physically impossible to have a space that is accessible to local artists and the public. Israeli-imposed access and movement restrictions on Palestinians became much tougher and more tightly controlled following the Second Intifada in the early 2000s.

It is almost impossible for the creatives in Gaza to participate in exhibitions in the West Bank and Jerusalem, and impossible for them to do so in a Palestinian urban centre inside Israel, such as Jaffa or Haifa. For Palestinians in the diaspora, especially those with passports from the Arab world, Gaza, the West Bank, Jerusalem and Palestinian locations inside Israel are out of reach. For Palestinian artists who hold Israeli passports, they cannot participate in exhibitions or festivals, or take up art residencies, in key regional art centres like Beirut, Sharjah and Dubai. Even many grants open to “Palestinian artists” by international organisations exclude them if they are Israeli citizens.

Inas Halabi is a Palestinian artist, born and raised in Jerusalem, who holds an Israeli passport. In 2016 she received the top award in the AM Qattan Foundation's Young Artist of the Year Award (YAYA) for her video work, Mnemosyne. She knows this reality well.

“Some of us have some doors open and others shut,” she says, by phone (she is part-way through a two-year art residency in Amsterdam). She tries to maintain a positive and determined approach and sees the Palestinian Museum as an important institution that can build on changes to the art scene back home.

“It is still early days, it’s paving the road,” says Halabi. “It’s a space that’s opening up the scene more internationally through exhibitions like Tahyah Al Quds, and it’s providing a platform for local and international artists, curators, and artists working across different visual media. It’s creating a space for dialogue and the exchange of ideas and aesthetics on a bigger scale than already exists in Palestine.”

'New ways of resisting the occupation'

Halabi, Persekian and many others in the visual arts scene are acutely aware of the need to work differently and creatively to overcome the challenges – from new artistic approaches to the ongoing issues of colonisation and ethnic cleansing they face, to fresh and engaging ways to create spaces where this dialogue and interaction between artists and the public can be developed.

They see multi-location festivals like the last Sharjah Biennial (which had off-site exhibitions in Ramallah, Beirut, Istanbul and Dakar), and Palestine’s own Qalandiya International (QI) Biennial as new and powerful forms of artistic resistance that are reinvigorating the arts scene in Palestine. QI invites partner organisations from across Palestine and the diaspora, along with international artists, to participate with an art programme under the same theme in their respective cities.

Persekian has played leading roles in establishing and running each of these biennials, and his second gallery, Al Ma’mal Foundation for Contemporary Art, is part of a network of Palestinian arts organisations in Jerusalem, called Shafaq. This network was created to attempt to collectively revive the art and cultural life of the city as a Palestinian city which has been adversely affected by political instability, increased isolation, and decades of economic and social neglect.

Al Ma’mal also recently started opening up its gallery space to host a regular series of concerts. Persekian was inspired by a similar approach taken by the Khalil Sakakini Cultural Centre in Ramallah. “It has started bringing to our exhibitions a whole new group of people, especially younger generations who would otherwise not come,” says Persekian.

For Halabi, these multi-location festivals and exhibitions help mitigate the divisions between Palestinian artists and the public, and their international counterparts.

___________________

Read more:

Reem Fadda's Jerusalem Lives at the Palestinian Museum

Shifting Ground, Ramallah: art under occupation

Architects of hope: rebuilding Gaza and imagining a Palestinian state

___________________

“These are new ways of resisting the occupation. It’s about bringing the audiences and artists together in conversation, creating more opportunities. It’s about trying to make things happen despite the occupation – there are artists who can’t move around, still we’re finding ways to make these conversations take place whether through different places in Palestine or the Arab world – I think it’s happening.”

And according to Jardaneh, the Palestinian Museum plans to be involved in this transformation to the visual arts landscape. “Working with these organisations and the community is also in the core of our strategy. We are a young institution and we need some time to deliver on the big goals that we have set for ourselves in this challenging environment,” she says.

If this momentum builds, might a renaissance of resistance be in the offing in Palestine?

The Palestinian Museum is in Museum Street, Birzeit, West Bank. For more information see www.palmuseum.org