Imaging technologies, such as photography, video and film, represent the visible, rendering an ostensibly identical picture of what we see before us.

However, when it comes to the Arab artists in Trembling Landscapes: Between Reality and Fiction, which is on view at the Eye Filmmuseum in Amsterdam, the reality is a bit more complicated.

In a historical colonial context, photography was a key part of the colonising project; the landscapes produced by maps were used as methods of control. Work after work in this exhibition shows that photography, film and video are not to be trusted.

“The technologies of photography and filmmaking have been very important in colonial discourses,” says Nat Muller, the Amsterdam curator and scholar with long experience in the Middle East behind the exhibition.

“The region has been controlled from map-making to aerial surveillance, not just in the Sykes-Picot line, but also in the Orientalist image of the Middle East as a vast desert of emptiness, or as a place of ruin and war. The idea of landscape has itself been weaponised.”

These ideas hold together a show that draws on 11 prominent Arab artists, including Larissa Sansour, Wael Shawky, Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme. Muller says she deliberately chose major artists from the region because of the lack of familiarity with Arab contemporary art in museums in the Netherlands.

As the title suggests, the works frame images of the land in both fiction and documentary modes, with special attention given to the latter.

In Jananne Al-Ani's Shadow Sites I (2010) and II (2011), for example, the Iraqi-born artist shows aerial footage of southern Jordan taken just before sunset, when the long shadows thrown by the low sun reveal usually occluded material – a technique known in the military as shadow tracing.

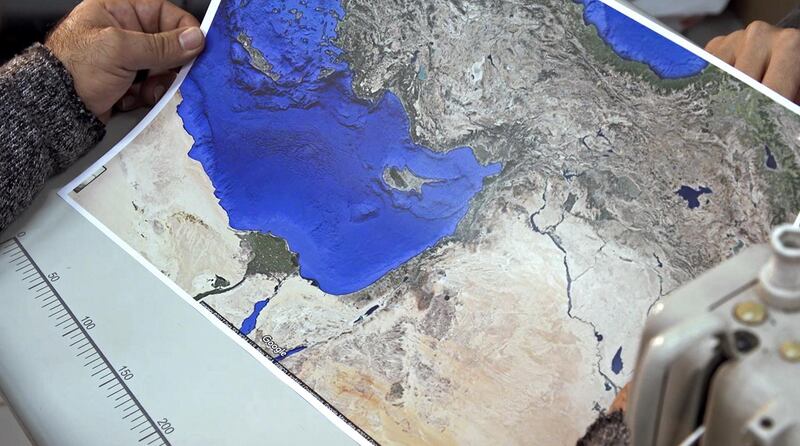

The idea of the work bringing to light invisible tensions also motivates the aerial maps of Lebanese artist Ali Cherri's Trembling Landscapes (2014-2016), from which the show adapted its title. Cherri notes the geological fault lines that lie beneath Algiers, Beirut, Damascus, Erbil, Makkah and Tehran: lines of instability that trespass the region's borders.

Other works draw upon informal knowledge, such as that shared by marginalised or migrant groups as they form their own maps of the region. Heba Y Amin's series of photographs, The Earth Is an Imperfect Ellipsoid (2016), compares an account of West African trade routes made by 11th century geographer Al-Bakri to the paths that contemporary migrants take into Europe. Amin followed the routes herself, documenting their geographical positions with Al-Bakri as her guide.

In Mohamed Hafeda's video Sewing Borders (2018), marginalised communities in the Lebanese capital sketch out the routes they take to avoid government checkpoints and other borders throughout the city, sewing these on to a map.

Contrasting with cartographic representations are works that focus on human narratives. Wael Shawky's magnetic Al Araba Al Madfuna II (2013), the second in a trilogy taking place in an Upper Egyptian village, is inspired by stories by Egyptian writer Mohamed Mustagab. One after another, residents of the village are struck dumb by a mysterious illness, and the inhabitants look to folk tales to try and assuage the jinn whom they believe afflicted them.

The story is acted by children, but voiced by adults, making it a series of disjunctions: the split between children and adults, the folkloric beliefs and the classical fusha that is spoken, the timelessness of the rural setting versus the years the story spans. All of them call into question who should be trusted with knowledge.

Armenian-Syrian artist Hrair Sarkissian's two-channel video Homesick (2014) performs his symbolical distance from his parents' home in Damascus. One screen shows the artist wielding hammer blows, and another the edifice crumbling, but his tool never makes physical contact with its object.

Works such as Shawky’s and Sarksissian’s help nuance the more clinical portrayal of landscape that dominates elsewhere, returning focus to the inhabitants of landscapes rather than their representations.

In a European context, landscapes emerged in the 17th century, as people left rural areas for cities. Once the land was no longer an entity to be lived and worked upon, it re-established itself as an object of desire. Despite the flat horizons of the Netherlands playing a key role in the genre, very little of this tradition shows up in the work of the Arab artists in the exhibition: no romantic view of craggy rocks, no vistas dominated by a landowning figure, no imagined hamlets alongside winding roads.

If we had to generalise, the relationship of these moving-image works with the land feels more vexed, attenuated, problematic, than such aggrandising depictions suggest.

If landscapes in the Dutch tradition were painted for a bourgeois audience, these artists understand their role as providing societal critique. And it’s hard to ask them to be sanguine: their subject matter, of wars, surveillance and hazardous migrant conditions, demands sobriety.

Indeed, the one work that hews closest to a conventional painterly "landscape" is Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige's Waiting for the Barbarians (2013), a four-minute composition of still photographs of Beirut's cityscape at night, stitched together to form a panorama, while a voiceover recites the Greek-Egyptian Cavafy's poem decrying the laziness and incompetence of political leaders.

The work has now taken on a second layer of importance: it bears witness to a port that has now been decimated, and Cavafy’s lines ring stingingly true. The Beirut port offers a beautiful vista, but there’s no romanticising what the work reveals.

Trembling Landscapes: Between Reality and Fiction is at the Eye Filmmuseum in Amsterdam until January 3