The United States has a long memory of being a young country, and so it tends to have a pronounced fondness for historical anniversaries. Recently, the 150th anniversary of the beginning of the American Civil War sparked a small library’s worth of new titles about every possible subtlety of that bloody conflict. Likewise, the anniversary of the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941 typically brings dozens of new histories.

Volumes commemorating tragedies, such as the assassinations of John F Kennedy or Martin Luther King Jr, or about the 9/11 attacks, also tend to generate rafts of studies, designed as much to rehearse a national narrative as to shed new light on old events. Victories, attacks, the wrenching deaths of public figures – everything is fair game. Except mistakes. Except embarrassments.

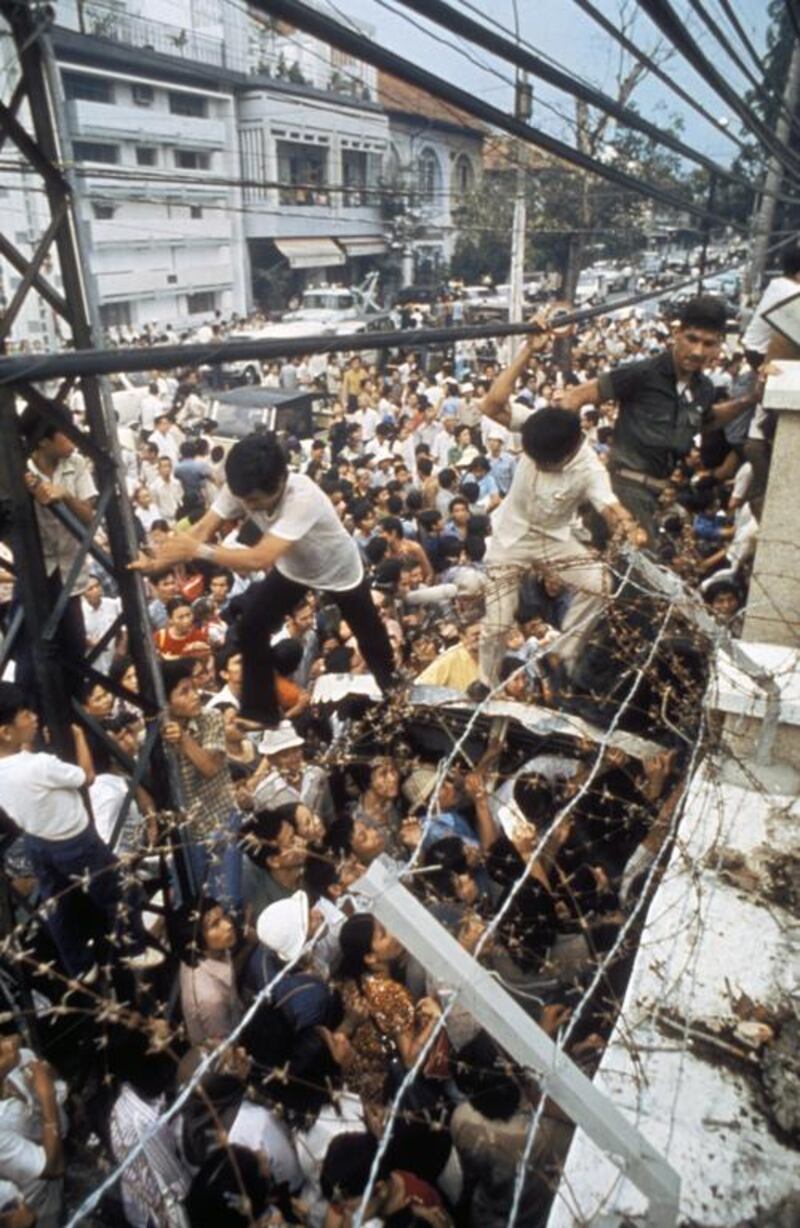

Thus comparatively little fanfare and only the softest of spotlights accompanies the 40th anniversary of the fall of Saigon, on April 30, 1975, captured in photos showing the hurried evacuation of American civilians by helicopter from a Saigon rooftop on the 29th and US troops dumping helicopters from aircraft carriers to make room for more civilians. The 30th marked the victory of Vietcong forces and the end of a war that had cost millions of military and civilian lives in the 10 years since conventional US ground troops were first deployed to South Vietnam by president Lyndon Johnson. Johnson’s successor, Richard Nixon, had hugely escalated US involvement, and after his resignation in 1974, Gerald Ford was handed this indefensible legacy.

The actual deployment of troops initially enjoyed public support, but the things that sustain this were exactly the things the Vietnam War stubbornly refused to supply. There were major battles – Ia Drang Valley, Khe Sanh, the infamous Tet Offensive – but they mostly weren’t set pieces, and they weren’t clear victories, and as the months wore on and the casualties mounted, reports of mismatched defeats, fruitless stalemates and horrific civilian massacres, such as at My Lai, began reaching the States. The press began using the deadly word “quagmire”; more US troops began returning in body bags or mentally shattered, young people began burning their draft cards and their parents and friends began wide-scale protests against the war. The Johnson administration became embattled over the issue, with the president hearing chants of: “Hey, hey, LBJ, how many kids did you kill today?”

This 40th anniversary, then, has provoked comparatively little in the way of institutional nostalgia. Gordon Kerr's excellent A Short History of the Vietnam War does an admirable job of putting the whole sloppy nightmare, full of "contradictions and puzzles", in perspective for a generation young enough to view it only as an item in a history book. He refers to the speech Ford made at Tulane University, in which he made it clear that "America was finished with Indochina and the war should be consigned to history".

"Today, America can regain the sense of pride that existed before Vietnam," Ford said. "But it cannot be achieved by refighting a war that is finished as far as America is concerned." Finished, and yet not: the decade of America's military involvement, culminating in crushing defeat, created substantial national fallout. Christian G Appy's more ambitious and harrowing American Reckoning, is a brilliant study of that fallout. Appy concentrates on the ways the Vietnam War has seeped into the social groundwater like a toxin, fundamentally altering the American public's reaction to all its government's future military engagements, from El Salvador to Kosovo. Appy sees a counterweight to this "profligately interventionist foreign policy" in the fear of every American president since Johnson to avoid "another Vietnam", but he lays some of the blame for interventionist failures at the feet of his fellow Americans. "As long as we continue to be seduced by the myth of American exceptionalism, we will too easily acquiesce to the misuse of power," he writes. And the misuses of that power have dire consequences, as he makes clear: "The US bombing [of Cambodia, from 1969 to 1973, in an attempt to strike at North Vietnamese troops] had helped bring to power one of history's most genocidal regimes, one that starved, worked to death, and murdered at least 1.5 million of its own people." Much like the humid jungles in which so much of it was fought, the Vietnam War had quite a capacity to fog the perceptions of those involved in it.

This applied equally to the soldiers on the ground as to the politicians back in Washington, and the two sides of the effect are seen in two more recent books. In Kenneth Payne's The Psychology of Strategy, the view is broad and largely theoretical, analysing the ways politicians and analysts in the Johnson and Nixon administrations could continue to make such self-evidently bad choices when a "rational actor would have walked away". Payne concludes with acid simplicity: that the entire story of Vietnam is one of strategists, some of them brilliant, simply not understanding the full extent of the risks involved in fighting this kind of war – and hence overestimating their ability to shape events on the ground.

At one point Payne mentions that "diaries can capture some of the immediate circumstances of decision-making", and it is certainly true that the burgeoning field of Vietnam diaries and memoirs provides some of the most fascinating reading on the subject. One good example is Vietnam Memoirs Part 1 by Don Bonsper, an account of the author's one-year tour of Vietnam serving as a Marine platoon leader from 1967 to 1968, taking over a unit whose previous 12 leaders had been killed or wounded. Bonsper, a Fulbright scholar from Portville, New York, went into the war with a strong sense of purpose, and although he would go on to be awarded both a Silver Star and a Bronze Star, his straightforward account is so readable mainly because it's so human: here we get the quotidian details that are usually dropped from larger narratives. And we get plenty more of Kerr's "contradictions and puzzles", as when Bonsper reflects on the feeling of aimlessness that filled much of his time. "I don't know about the enemy, but I knew I was usually confused," he confesses. "It seemed as though we just walked and moved and patrolled and searched … I was never sure what the big picture looked like or what the overall plan was."

It’s precisely this deep uncertainty that still clings to the whole subject of the Vietnam War even today, 40 years after the whole debacle ended. It makes for particularly sombre memorials – and problematic anniversaries.

Steve Donoghue is managing editor of Open Letters Monthly.

thereview@thenational.ae