Vibeke Løkkeberg's documentary Tears of Gaza has created a storm in her native Norway. Ib Thomson, the cultural spokesman of the opposition Progress Party, has complained about public money being used on a film that he sees as having taken an anti-Israeli stance in the way that it looks at the Israeli bombing of Gaza that recommenced in December 2008.

The director who is making her first film in 17 years says that she expected the accusations of bias. However, she argues: "For me, my focus is on the victims. Who are these bombs falling on? I'm not interested in political analysis. I'm just an observer, and I'm allowing the audience to see what the people and the victims are going through in Gaza. In Afghanistan and in Iraq we haven't seen the situation in such a close way either."

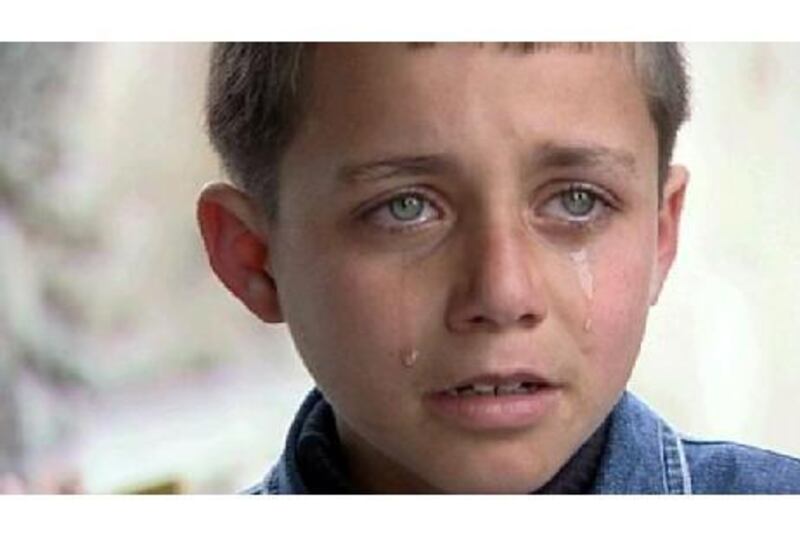

The director does not shy away from showing the destruction caused and the human cost of the action. One notable sequence shows the dead bodies of children being pulled from the rubble with onlookers visibly shocked at the devastation they are witnessing.

The 65-year-old director argues she was able to get so close to the action through several unique partnerships with Palestinians on the ground and also with a Palestinian camera crew.

"The movie has a very interesting way of being made," Løkkeberg explains. "The people taking the photos and shooting the images of the bombs are almost being bombed themselves because they are so close. But you must remember that foreigners and news agencies were blocked out - if you wanted to go into Gaza during that period you were not allowed in, just as if you wanted to go outside of Gaza during that period, you were locked out.

"So as I was locked out, and the Palestinians were locked in - it was very important for me to make a hole in that wall and provide images to the world that the Israelis didn't want to show. A lot of people inside Gaza have cameras now on their phones so they can document all this, and this is fantastic."

However, not everything on screen is documentary footage. The director tells the story of what happened in Gaza through interviews with children and their families. She wants audiences around the world to have empathy with the stories and she believed this was best achieved by showing personal testimony.

"I had a script and had a scenario for the children and also the interviews, which were all done after the recent war," she adds. "When it came to the war, I have five minutes of archive footage that I bought, but all the other extreme documentary evidence is shot by contacts inside Gaza. Once everybody knew I was making this film, they collected images. Also, I had to search for material that would confirm what the children were saying in the interviews. So if a child says, they bombed my school, it's not enough to hear them say it, we would have to see that the school was bombed, so I searched for that too. It's a film that shows the images that confirm the human-rights organisations were right when they made reports on the atrocities committed."

Løkkeberg believes the advantage that the documentary-film format has over the internet and news channels is that it's harder for an audience to ignore images when they don't have an easy option of switching channels or looking at another website.

The disadvantage of course, is that it reaches a smaller audience and most of those who pay to see the film will already have some sympathy with the director's point of view. She says that it's enough, however, to know there are some people in the middle ground who will see what is going on - and knowing that makes the risks taken to film worth it.

A former actress and the director of nine films, including Hud, which played at Cannes in 1986, she is often accused of courting controversy. She argues: "Well, I suppose all my films have been very controversial, and they have a big resistance in Norway. In contrast, I have been in Cannes with a film and I've always been well-received abroad, but [Norway] is a small country, and I've always received a lot of flak.

"It's like if you live in a small street and someone does not agree with you, then the whole street quickly agrees that it must be bad also. They just want to follow the group. So I had lots of discussions over all my movies, and then in the last 17 years when I haven't managed to make one, I went over to writing novels and I wrote five novels."

Her last novel, Allies is a family chronicle and may explain why she is so interested in the plight of victims who are ignored. The book tells how the Norwegian resistance movement knew the English were about to attack a submarine bunker on October 4, 1944, and kept their children at home. However, those without prior knowledge, including Vibeke's brother Hakon, were not so lucky. Although her brother survived, 200 others - 70 of them children - died.

She admits: "So my background is having this physical thing happen to so many people in my family, so I know what it is like [to feel injustice]. This story of the alliance bombing has been hidden from the history books. I started to write about it and there was so much anger directed at me from the resistance people in Norway because they didn't want this to be written about."

She believes it is her duty to question orthodox opinion: "I think that an artist always has to find out what a government tries to hide from the people. This is always what triggers me - we are just people, and we are getting lied to. I want to find out what they are trying to hide."

Ÿ Today, Marina Mall Cinestar 2, 5pm

* Kaleem Aftab