Jonathan Hoffman spends his spare time raising money for schools in Afghanistan and, in the summers, visiting the country to build them. Hamida Ghafour talks to the American teacher who hopes to defeat the violence in the country through education, one school at a time. Most American teachers spend their annual summer holidays doing refresher courses, or perhaps in a special year travelling to Europe for a few weeks. Jonathan Hoffman spends his building schools in Afghanistan.

Each trip takes a year to organise. One evening a week, for example, he works as a night supervisor at the high school in Vermont where he teaches, and puts the money aside to pay for his flights and hotel. Currently, he is busy raising money for the schools, gathering a few dollars here and there from kind-hearted people in his hometown who are interested in helping a faraway place where American soldiers die every day.

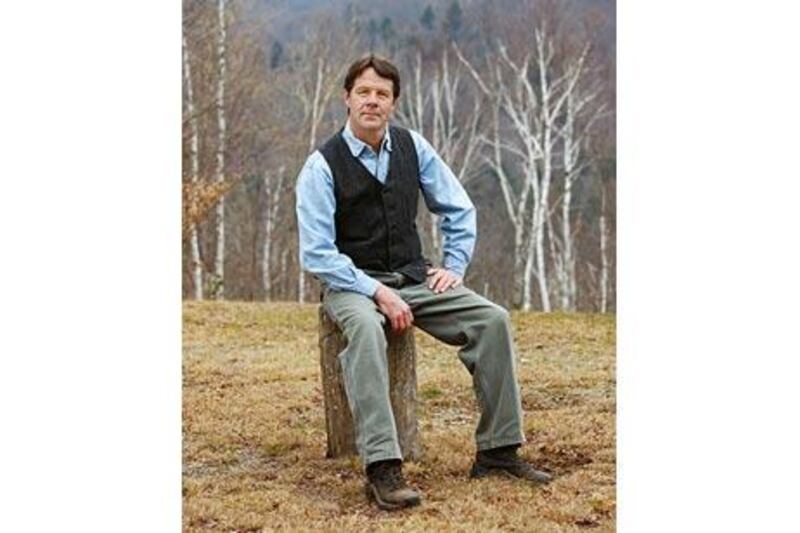

"It will take a while but I do believe that over time, removing the desperation in everyone's lives would ease the violence in Afghanistan," he says. It is a typical, no-nonsense comment from Hoffman, 50, who has made eight trips in as many years to build 11 schools. In a country where large-scale aid organisations operate with huge numbers of staff and security, Hoffman is one of the few with a direct and practical approach that contradicts how most development work is done.

The relationship between the Afghan civilian population and the development community has been at an all-time low since October 28, when five United Nations workers were murdered by militants who burst into their guesthouse in Kabul. In the aftermath of the killings, hundreds of UN staff have temporarily relocated to Dubai for two months, pending a security assessment of Afghanistan. Until security improves, most organisations have restricted or stopped their staff altogether from working in parts of the country where their help is needed the most, fuelling the perception among Afghans that the billions of dollars in aid money is being frittered away.

As a result, security and development, which are considered crucial to the country's stability, have become like the proverbial conundrum of the chicken and the egg: no one can agree on which should come first. The US president, Barack Obama, announced on December 1 plans to send about 30,000 soldiers early next year to turn the war around. This deployment will be complemented by a civilian component involving the UN, which carries out the most high-profile and visible development work.

But Hoffman, who runs Direct Aid International, an American-registered charity, is unperturbed by the escalating violence and is planning next summer's trip. For him, it is the small projects such as schools that will make the difference in the long run. He arrives each July with up to US$40,000 (Dh147,000) in cash, and with the help of an Afghan friend, who is also a member of parliament, they choose a few villages without schools to approach. They head there with a driver, an interpreter and a security guard.

Hoffman only builds in ethnic Hazara villages in central Afghanistan for safety reasons. The Hazaras are Shiites and do not support the sectarian Taliban insurgents. He gathers all the village elders in one room and tells them they have US$10,000 (Dh37,000) to build a school. Immediately, a sense of collective responsibility is established. "I take pride in promoting self-reliance and governance and giving the village a chance to rally around a project. I have been pleased with the results. I ask every male in the village to donate one day to help with labour, either bringing big stones from the mountains to break them for the school, or donate a trunk of a poplar tree. The elders draw the blueprints in the sand. The mason and his helpers are the only ones who are paid for labour."

Travel is difficult and he has had close encounters. "Over the years I have gone from wearing blue jeans and a jacket to disguising my presence and travelling like a local." In one instance, Hoffman and his team were driving through Ghazni province when they came under fire from the insurgents' rocket-propelled grenades. "Aside from my driver, who was shot in the leg, no one was hurt. But we did get two of theirs; one was the one with the RPG."

Hoffman says the Afghan police go out of their way to protect him. "Numerous times over the years I have had over 50 Afghan police and militia assist me and my team to travel certain corridors safely by positioning their men on the mountain tops at midnight to hold the hill until I travel the following morning," he says. "I wave to them and they wave back. It is moments like that which remind me of the actual danger I put myself into. I must admit that the past two years were the hardest to travel. Sometimes it took three or four days to make a one-day journey.

"The aid organisations have to take a similar approach as the military. You have to leave the base, be prepared for loss of life within the ranks. I know there are some who are prepared to travel outside of Kabul. Security is an issue and proper precautions should be taken, but the notion of working in a country such as Afghanistan and allowing security issues to drastically hinder development projects is confusing."

Hoffman, a chef instructor for 13 years at a technical high school that offers vocational studies, became interested in development work after volunteering in war-torn Kosovo in the late 1990s. After September 11, he decided to put his skills to use in Afghanistan. He raised enough money for a three-room stone and cement school house for 86 girls in July 2002. Following that he decided to dedicate every summer to his Afghan cause.

His only condition when negotiating with the village elders is the school must be built from cement and not the traditional baked mud bricks because they do not last long. It is also up to the village to find its own teachers and supply students with notebooks and pencils. "I have seen numerous villages that are in desperate need of a new school or supplies. As I understand it, most of the teachers are hired from local high schools as they graduate from 12th grade. I have also seen two boys fight over a pencil and have had children at an orphanage in Kabul ask me for pencil. Not money or candy or even adoption, but a pencil."

Most crucial of all, he will not tell them what, or whom to teach. "They know that I want women to attend school. I ask about levels of education offered to both boys and girls but never tell them to change their system. In most rural villages the father determines how long his daughter will attend school. I cannot be certain but do believe that the level of education the father holds determines the level his daughter will obtain. The higher his education, the further he will allow his daughter to attend."

He continues: "This might sound politically incorrect, but we must educate men before women will be allowed a full and open education. I don't mean we should stop educating women but we should introduce curriculum that educates men to the value of an educated wife and not be threatened by it." His years of travel to Afghanistan have taught him some harsh realities about rural life and how difficult it is to pass judgement on people with different values.

"All hands, both young and old, are necessary to get the winter fuel, feed for livestock and getting the crops in before winter sets in. This can lead to a decision by the male figure as to which is best: send them to school or send them to the scraggly hillsides and mountains with grandpa to cut shrub and bale it and walk back holding it securely on the mules. When it takes the entire season to get ready for the snow it leaves little time for play, travel, education or leisure of any kind."

But other cultural differences are simply too difficult to bridge. His Afghan friends ask every year why he is not married with children. "I am openly welcomed with banners, great ceremony and celebrations. They have offered me land, asked me to move there and take a local Afghan for a wife. I tell them if I were married I would not be here. They accept the comment but tell me as I leave that they will pray for me and maybe next year I will have a wife."