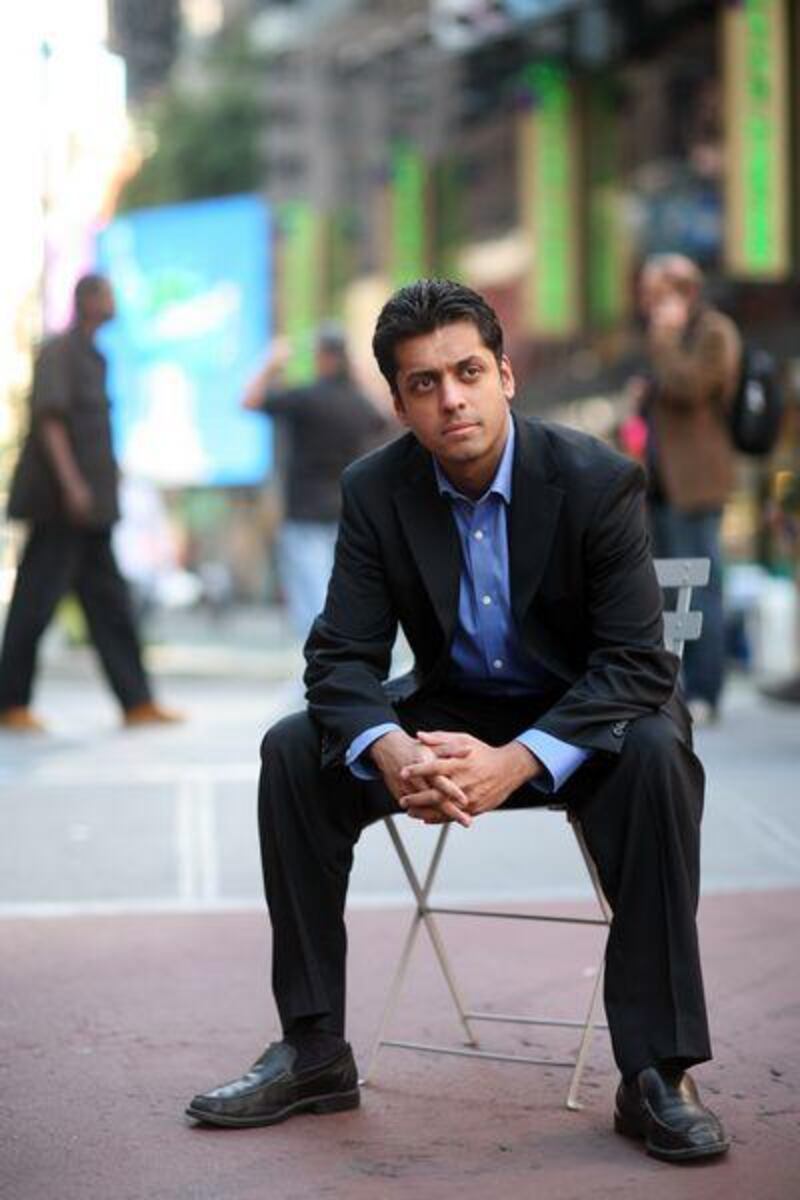

Wajahat Ali joined the cast for a standing ovation at the end of last Friday's performance of his play The Domestic Crusaders on the stage of a small New York theatre. For the 28-year-old Pakistani-American, it was a moment of triumph barely imagined during the almost eight years it took to write, produce and stage his play.

Critics have acclaimed The Domestic Crusaders as one of the first plays about Muslim life in the United States. With humour and affection, Mr Wajahat portrays six members of a Pakistani-American family and their inter-generational misconceptions, all within the wider world of American life that includes racial profiling and anti-Muslim bias. The family reunites for the 21st birthday of the younger brother, who proceeds to shock his traditional parents with the revelation that he does not want to be a doctor but a teacher to inform the world about Islam. "You will get the blessings of my work," the son tells his parents.

"We have enough blessings," says his mother. "You can bless us by becoming a surgeon. You like kids? Become a paediatrician. Teach them Islam as you give them their lollipops." The play also introduces us to the younger son's political activist and hijab-wearing sister, who is dating an African-American Muslim convert, and his womanising older brother. Their father is being frustrated in his bid for promotion at his office job while the mother alludes to giving up her career ambitions to be a good wife. Their grandfather, meanwhile, remains haunted by memories of violence committed during Partition that led to the birth of Pakistan and India in 1947.

Mr Wajahat's decision to premiere the play in New York on September 11, the eighth anniversary of the World Trade Center attacks, aroused some controversy. He also had to contend with community misgivings about his sometimes unflattering depictions of Pakistani-Americans. But the playwright, who works by day as a lawyer in California, felt impelled to convey the Pakistani-American experience, both its cultural specifics and its commonalities with any other middle-class family.

"I was overwhelmed with a sense of urgency when writing the play. Truth resonates through fiction," he said. "It's a portrait of a family that's just like any other family without proselytising." The play was not autobiographical, said Mr Wajahat, who is the only child of parents who run a financial services company. He drew his inspiration from different people including numerous "aunties" who speak "Urdish", a melange of Urdu and English, who have tried to marry him off but without success so far.

He said the play's audiences were mixed, often dominated by Americans of South Asian descent but including African-Americans, Latinos, Jews and all ethnic groups. "There are so many misconceptions out there," he said. "One lady told me she was shocked that Fatima [the sister's character] did not become a suicide bomber because she wore the hijab! She didn't mean to be mean and she liked the play, but that's what she had thought."

Mr Wajahat described himself as a "practising but not pious" Muslim who straddled East and West. "I don't have a beard and I have non-Muslim friends and I talk to women," he said. "But I fast, don't drink and pray." He rejected the notion that Islamic art should always fulfil "dawa", meaning persuading non-believers to the faith. "People in the community asked me why didn't I write something Islamic, which I'm not averse to but I don't believe all Muslim art should be propaganda to convert people. Some people want to only show us as avatars of perfection but there are racists and misogynists.

"Other religious people have told me they do get it and they enjoyed the play." Mr Wajahat started writing the play in the immediate months after the September 11 attacks when he was still a student. He also spearheaded fund-raising efforts using the internet to generate the US$31,000 (Dh113,866) to stage the play in New York at the Nuyorican Poets Cafe. He solicited advance reviews and won praise from prominent celebrities including Emma Thompson, the Academy Award-winning actress, and Yann Martel, the Booker Prize-winning author.

His first donations came from a Vietnamese community group which called his work an American, rather than Muslim, play. Pakistani-Americans initially were reluctant to support him. "I had to engage the community and reach out to people who laughed at me," he said. "We are a young community here in the United States and we don't push our kids into the arts so there was some suspicion too." There is a 50-50 chance of the play reaching Broadway and producers in London and Dubai are also interested in staging it, he said.

Meanwhile, Mr Wajahat was thinking about tackling a novel and writing more journalism in his time left over from working as an attorney specialising in clients facing financial difficulties. "I've also written the first scene of a sequel to DC," said Mr Wajahat, using his nickname for The Domestic Crusaders. "Too many people keep asking what happens next to the characters."