Every year, between December 15 and January 15, hundreds of thousands of people across India congregate in Chennai, the capital of the southern state of Tamil Nadu, for its Carnatic and Bharatanatyam festivals. More than 300 concert halls in the city host cultural events throughout the month in a tradition that has endured for more than half a century.

But each year, as audiences clad in silk saris and white dhotis arrive, an ugly issue rears its head: the discrimination against female performers by the show organisers and male musicians.

In a recent post on Facebook, Kalpana Mohan, a California-based writer, highlighted an incident that happened two years ago at a concert hall in Chennai. A prominent male vocalist kicked up a fuss when he realised he would have to perform alongside a young female violinist. An older, established musician, he refused to take the stage with a junior female artist. The organisers found a male violinist to replace the female artist, leaving her in tears.

After describing the incident in her Facebook post, Mohan ended with an appeal for gender equality: “I do hope December 2014 is the season in Chennai in which artists, young and old, fight back, ask questions, write to local and national newspapers and launch a campaign to fix the cracks, while simultaneously fixing the crackpots who believe that a woman is inferior – when all that matters is prowess, not age or gender. I certainly hope that this is the year that older, established vocalists, both female and male, step up and fight for the sake of their younger female counterparts. I hope that the next time something like this happens, the rest of the performing crew unites in support to protest the injustice.”

When The National contacted the violinist who wasn't allowed to play, she declined to talk about the incident: "I wish to tell you that it does not interest me. I would rather focus on my music," she said

Oddly enough, nobody in the Chennai music circles blames her for her reluctance to comment, because Carnatic music has traditionally been the bastion of men. In this rigidly hierarchical and patriarchal set-up, female performers don’t want to be seen as troublemakers, especially if they are young, because of the repercussions it could have on their career.

“It is unfortunate and terrible,” says pianist Anil Srinivasan, who works with a variety of performers, male and female. “But the only way forward is for women to band together and boycott all those musicians and percussionists who are saying such things. The audience should also show their support by boycotting concert halls that allow such inequality to go unchecked.”

Anita Ratnam, a renowned classical dancer, says: “Senior male performers would rather accompany a junior and emerging male vocalist than sit beside an established and accomplished female singer. It is appalling. Nobody does anything about it, so the abuse continues. Female artists should speak out, not with anger but with confidence.”

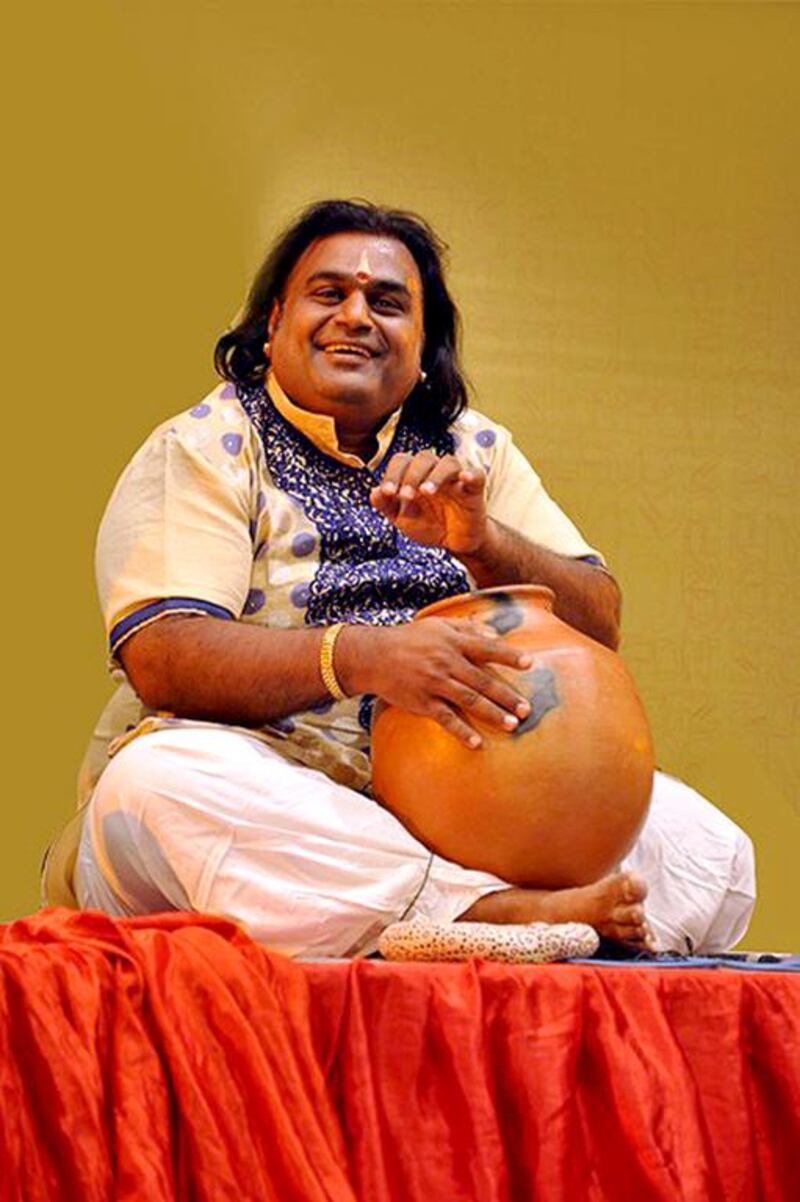

Ghatam Karthick, a young percussionist who plays the ghatam (pot), gives some context. “Legendary percussionists such as Umayalpuram Sivaraman, T K Murthy and Palghat Raghu were used to accompanying exclusively male singers,” he says.

“Until the ‘trinity’ of female singers – D K Pattammal, M L Vasanthakumari and M S Subbulakshmi, who won the Bharat Ratna, India’s highest civilian honour – found success, no male accompanist would work with women,” he says.

Karthick credits female singers and musicians for his big breaks. His first concert at the Madras Music Academy was with the well-known vocalist Charumathi Ramachandran, he went on his first foreign tour with the veena player Veena Gayathri, and says his career soared after he played alongside top female singers such as Sudha Ragunathan and Bombay Jayashri, who was nominated for an Academy Award for Pi's Lullaby in Life of Pi (2013).

“I owe everything to women,” Karthick says matter-of-factly, but agrees that no effort is being made to challenge senior male performers who practise gender discrimination.

“Will we need a Nirbhaya in the music world?” asks the eminent veena player Jayanthi Kumaresh, referring to the 2012 Delhi rape victim whose brutal death drew attention and galvanised support for improved attitudes towards women across India.

artslife@thenational.ae