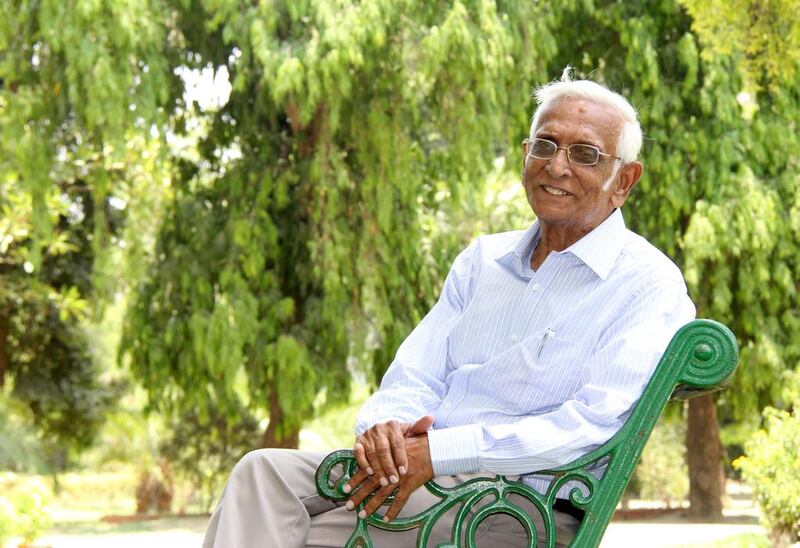

In some ways, it was probably inevitable that M I H Farooqi MSc, PhD, would end up writing books about the plants of the hadith and the Quran. Botany and Islam are in his roots.

Not only has the 79-year-old scientist dedicated his professional life to the study of plants and their uses, but he’s also the intellectual product of one of India’s most prestigious Islamic academic institutions, Aligarh Muslim University, as well as being the son of a widely respected Islamic scholar, Al Haj Maulana Abrar Husain Farooqi.

It was some decades, however, before the author of Medicinal Plants in the Traditions of Prophet Muhammad and the best-selling Plants of the Quran turned his attention to the finer questions of Quranic botany, such as the source of the Israelite-sustaining manna, the confusion surrounding the true identity of Quranic camphor and the identification of plant species associated with paradise (jannah) and hell (dozakh).

In 1961, a 25-year-old Mohammed Iqtedar Husain Farooqi left his hometown of Barabanki and moved to Lucknow, the city he still calls home.

It was here he joined the Indian government’s National Botanical Research Institute, first as a scientific assistant and eventually as assistant director, dedicating a 35-year career to the chemistry, economic botany and commercial potential of plants.

In the wider world, Farooqi may be known for his Plants of the Quran, but in botanical circles, his reputation rests on the authorship of more than 120 research articles, the first published in 1962, as well as for reference works such as his Dictionary of Indian Gums and Resins and Indian Plants of Commercial Value.

Farooqi first wrote about Quranic plants in the late 1970s, when he submitted an article about manna, a life-sustaining substance mentioned in the Bible and the Quran, to various Urdu-language newspapers such as New Delhi's Qaumi Awaz and Hyderabad's Siasat Daily.

“There has been a lot of work on the plants of the Bible, but I was one of the first to start researching the plants of the Quran in this way, and fortunately I was encouraged by Maulana Abul Hasan Ali Nadvi [one of the greatest subcontinental scholars of Islam in the 20th century] to write my articles in the form of a book,” Farooqi explains.

“The commentators of the Quran, the mufassirun, had applied their minds to the identification of some plants, but unfortunately, none of the commentaries provide a scientific description.”

Farooqi’s chapter on manna is an example of how the scientist has tried to achieve just that.

It begins with the plant’s Quranic name, Al Mann, and then lists its common names – the substance is known as turanjabin and kazanjbin in Arabic – before listing the plant’s likely botanical names and examples of where it appears in the Quran, for example in verse 57 of the surah known as “the heifer”:

“And We gave you the shade of clouds and sent down to you manna and quails, saying: ‘Eat of the good things We have provided for you:’ (But they rebelled); to Us they did no harm, but they harmed their own souls.”

Farooqi then embarks on a detailed explanation of how the plant has been identified in Islamic tafsir, or interpretation, attempts made by western scientists to identify it, the etymology surrounding its name and even how substances that may relate to manna are in use to this day.

The result is a cross between an encyclopaedia entry and books such as Richard Mabey's groundbreaking Flora Britannica, which is a kind of cultural as well as a botanic compendium.

In Farooqi’s case, there’s always the added element of Islam, and although the scientist insists that his work is not a commentary on the Quran or that his ideas are an attempt to change its meaning in any way, there are examples where he claims to have helped clarify certain long-running misunderstandings.

“There are 22 plants that are mentioned by their specific names in the Quran, whereas in the Prophetic tradition, about 50 plants are mentioned, mostly well-known medicinal plants – for example, the black cumin, the toothbrush tree, the senna, chicory, cress seeds, aloe, fenugreek, marjoram and saffron also,” the scientist says.

“Many of the plants mentioned in the Quran are common to Arabia and India; in fact, many of the plants that are mentioned in the Prophetic tradition, in the hadith, were imported to Arabia from India long before the advent of Islam.”

“So identifying the common plants was easy, but identifying the plants that are associated in different Quranic verses with paradise, jannah, and with hell, is very difficult, because in each of the commentaries of the past, they have given their own ideas, and the new interpretations, which I have given, have not always been accepted.

“There is a verse in the Quran that says that all good Muslims, when they reach jannah, will be provided with a drink in which camphor will be mixed, but this is not understandable,” he says. “Camphor is a toxic substance, and if you mix even a small amount with water, you cannot drink it.”

Farooqi’s answer is to identify the kafur of the Quran not as camphor but as henna or Lawsonia inermis.

“Many people do not accept the reinterpretation, but I am fortunate that some well-known Islamic scholars, including those from the Islamic University in India, have agreed with my interpretation and have said that my work has done much to remove confusion.”

Two of Farooqi’s other controversial interpretations involve the Quranic sidr, which has been commonly understood to refer to the tree we now know as Ziziphus spina-christi, but which he insists is actually the cedar of Lebanon (Cedrus libani), and the zaqqum, or tree of hell, which the scientist has identified as Euphorbia resinifera.

The first edition of Plants of the Quran was published in 1986. Since then, it has gone through nine editions and been translated into at least nine languages, including Urdu, Hindi, Kannada, Malayalam, Farsi and Bahasa (from Indonesia).

Farooqi says that almost 10,000 copies have been sold, although he says it’s impossible to put an actual figure to the sales, because the volume has been reprinted several times without his permission.

Although he remains a “humble scientist”, the success of Farooqi’s Quran- and hadith-related publications has led to international recognition.

In 2010, he received the congratulations and thanks of Mohammed VI, the king of Morocco; in 2011, he was awarded US$25,000 (Dh91,829) by Qaboos bin Said Al Said, the sultan of Oman.

The retiree’s latest project is a book about the animals mentioned in the Quran, which he hopes will be ready for publication this year.

“Mostly, I write now. Every few days, I get emails from newspapers and magazines across India asking for articles – I am more busy now than I was when I was working full-time,” he says.

“My wife complains that I did not give enough time to my family when I was working, and now that I am not [working], she says it’s just the same.”

nleech@thenational.ae