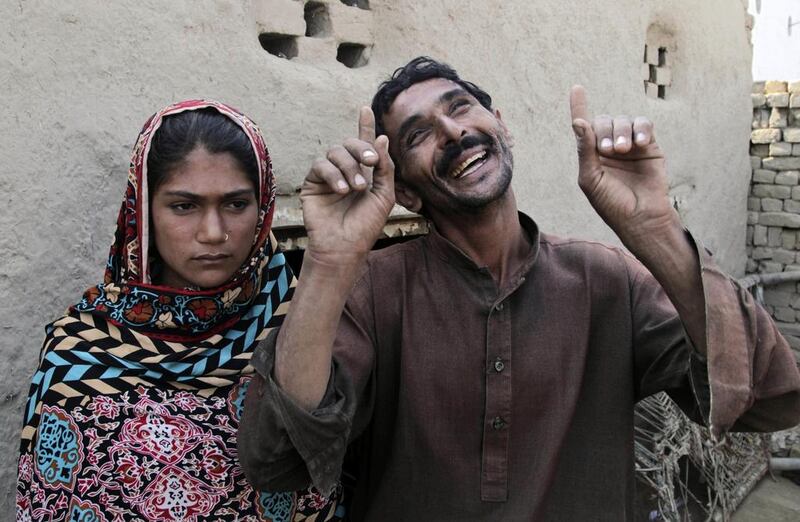

JAMPUR, Pakistan // Mohammad Ramzan is deaf and mute and has a childlike mind. But he knew his wife, Saima, was too young when she was given to him as a bride.

The 36-year-old uses his fingers to count out her age when they married. When he reaches 13, he stops and looks at her, points and nods several times.

The girl’s father, Wazir Ahmed, says she was 14, not 13, but her age was beside the point. It mattered only that she had reached puberty when he arranged her marriage as an exchange: his daughter for Ramzan’s sister, Sabeel, whom he wanted to take as a second wife. His first wife, Saima’s mother, had given him daughters, and he wanted a son. But Sabeel would not marry him until her brother had a wife to care for him.

She would be a bride in exchange for a bride.

“We gave a girl in this family for a girl in their family,” Ahmed says. “That is our right.”

In deeply conservative regions such as this one in southern Punjab the tribal practice of exchanging girls between families is so entrenched, it even has its own name in Urdu: Watta Satta, which means give and take.

A girl may be given away to pay a debt or settle a dispute between feuding families, or married to a cousin to keep her dowry in the family or, as in this case, married for the prospect of a male heir.

Many believe that Islam instructs fathers to marry off their daughters at puberty.

“If it is not done, our society thinks parents have not fulfilled their religious obligation,” says Faisal Tangwani, regional coordinator for the independent Human Rights Commission of Pakistan in nearby Multan.

Ahmed believes his daughter’s marriage to a disabled man was God’s will.

The fact that Ramzan is nearly three times his daughter’s age is irrelevant, he says. The legal marrying age here is 16, but in a rare move, police investigated Saima’s marriage after receiving a complaint, possibly from a relative involved in a dispute with her father.

Ramzan and Ahmed were jailed for a few days, but Saima testified in court that she was 16 – to protect her father and husband, she says – and they were released. In their world of grinding poverty, they are all trapped in a crippling cycle of centuries-old tribal traditions mixed with religious beliefs.

Fathers want sons to help support the family; wives must provide those sons and daughters must become mothers even when they are still children.

Saima’s mother, Janaat, agrees with early marriage for her daughters. Girls are a headache after puberty, she says. They can’t be left at home alone for fear of unwanted sexual activity – or worse, they might go off with a boy of their own choosing.

“That would be a shame for us. We would have no honour. No – when they reach puberty, we have to marry them,” she says. “Daughters are a burden, but the sons, they are the owners of the house.”

She also accepted her husband’s marriage to another woman. “I feel shame that I don’t have a son. I myself allowed my husband to get a second wife,” she says.

Her husband’s new wife, Sabeel, says she agreed to marry Ahmed because she wanted a wife for her brother.

“No one had been willing to give their daughters to my brother,” she says.

Ramzan’s home is tucked away in a narrow alley lined with open sewers. His elderly parents live with him. His father rarely leaves his bed, saying he has trouble walking. His mother spends her days begging, sometimes knocking on doors, other times sitting in the dusty road, her hand outstretched. Like Ramzan, she can neither hear nor speak. Both her hips and one knee have been broken.

“I said at the time, she was too young,” Ramzan says of his child bride. “But everyone said I must.” He holds his hand up to just below his chest to indicate how tall she was when they married.

Saima says little. “His sister and my father fell in love and they exchanged me,” she explains, matter-of-factly. “Yes, I am afraid of my father, but it is his decision who I will marry and when.”

Ramzan often reaches to touch the top of her head. Through gestures, he expresses fears that Saima will leave him one day, which would make God unhappy. Saima quickly became pregnant but miscarried at five months. Now Ramzan wants her to take medicine to make her become pregnant again.

Saima rarely looks at him but says she has no quarrel with her husband, nor does she plan to leave. She says she understands her husband’s gestures, yet it is his 12-year-old niece, Haseena – Sabeel’s daughter from a previous marriage – who does most of the interpreting. Haseena was 10 when her mother married Saima’s father but stayed to cook and clean for her grandparents. “When Saima married my uncle, my mother told me to leave school and be with Saima because she will be all alone at home,” Haseena says. “The family felt sorry for her as she was so young. “At her age, she should have been playing.”

The same fate awaits Saima’s seven-year-old sister, Asma. She is already promised to her cousin, who is about 10. They will marry when she reaches puberty.

* Associated Press