KABUL // After the Taliban came close to capturing the northern Afghan province of Kunduz two months ago, Farida Ahmad cast her mind back to better times.

In the early years of the US-led war, security was good and there were plenty of opportunities for enterprising women. Now, more than a decade later, caught between an emboldened insurgency and the lawless behaviour of pro-government militias, the aid organisation she runs is struggling to survive and she is scared whenever she leaves the house.

“It is not like the past, when we would participate in meetings and women would gather to meet and make plans. Now all of that is finished,” she said.

Kunduz lies on the Afghan border with Tajikistan and in late April it appeared to be on the brink of falling to the most ambitious Taliban offensive on a province since the war began. The assault sparked panic in the government, which sent reinforcements north from elsewhere in the country.

Amid widespread talk that senior officials in the provincial capital were about to flee for their lives, the city itself was saved from collapse. However, it was nothing more than a hollow victory, residents told The National.

Surrounding districts are still wracked by violence and families have not been able to return to their homes. The optimism of a decade ago is now gone.

The history of Kunduz since the 2001 US-led invasion mirrors the history of the war itself. Despite being far from the insurgent heartlands of southern and eastern Afghanistan, the province has a chequered past of hope and despair.

The provincial capital was the last city in the north to be held by the Taliban regime. Besieged by the Northern Alliance, hundreds of foreign fighters found themselves cornered, though some were evacuated by the Pakistan government.

When the city eventually fell, brutal reprisals were carried out against captured Taliban and suspected sympathisers before a relative calm settled over the region.

Under the Nato mission, German soldiers arrived in Kunduz in October 2003 expecting to see little combat. But by the end of the decade security had begun to deteriorate and in September 2009 a German-ordered airstrike in the province killed up to 142 people, most of them civilians.

The subsequent deployment of US forces to Kunduz as part of a nationwide surge failed to bring long-term security. Now, with most foreign combat troops withdrawn from Afghanistan, the bloodshed is rising.

“When the Taliban reached the gates of the city all the people were very scared, sad and worried,” said Ms Ahmad, whose name has been changed to protect her identity.

Like most Afghan women who work for aid organisations, she is used to taking risks. When the Taliban regime prevented girls from going to school in Kunduz, she ran underground maths, English and computer classes for them. Today she is so concerned about the situation she wants her real name withheld.

Before security began to deteriorate, her NGO had 300 women in one of its tailoring courses. Today that number has dropped to 50 and Ms Ahmad lives on her own, having persuaded the rest of her family to leave Kunduz.

She told The National violence had been escalating since the build-up to last year’s presidential election. Even in the city, any women leaving their house to get an education now do so “with a lot of concern”, she said.

Kunduz residents say the insurgents are only partly to blame for the insecurity.

Militias that were established in the province under US sponsorship to bolster the conventional security forces have been added to by the Afghan government since the Taliban offensive. It has mobilised hundreds of fighters to serve on its behalf under former mujaheddin commanders, and both these fighters and the Taliban are now being accused of extortion in rural areas, demanding money from people in the guise of religious taxes.

Abdul Zahir, a former army colonel and head of a council that works towards tribal unity in Kunduz, said villagers were tired of being intimidated.

“Behind each commander of a militia is a big politician in the central government,” he explained. “This is our main problem. If you complain again and again, it reaches that big politician and he will strengthen his support for them. These militias who operate here are not simple men that provincial officials can control or stop. They all belong to the big politicians in Kabul.”

With a diverse population that includes ethnic Pashtuns, Uzbeks and Tajiks, residents say communities are being played off against each other and left with no choice but to take sides. They said the insurgents came to within just a few kilometres of the city centre during the offensive.

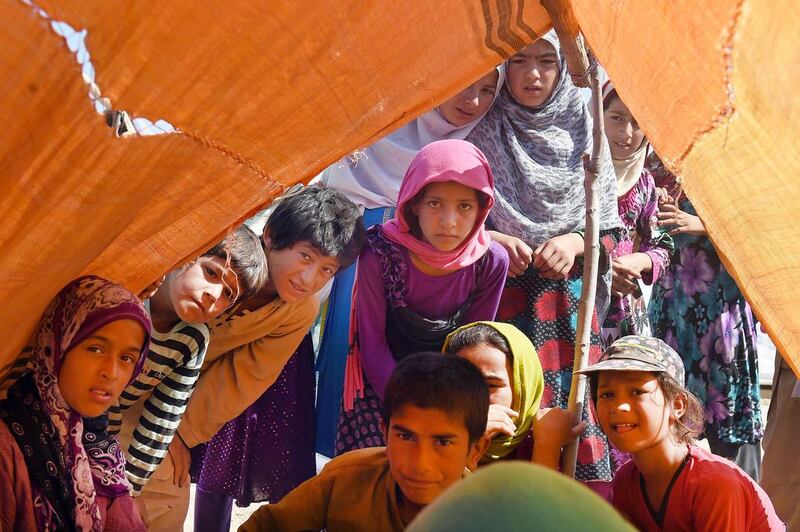

The UN said that as of May 21, about 18,350 families in Kunduz had asked the authorities to be considered as internally displaced and in need of emergency assistance. It said the Taliban’s offensive and the government’s military response had caused people to leave their homes.

Kunduz’s position as a potential gateway to and from central Asia makes it an attractive target for insurgents and the government has claimed that foreign militants linked to ISIL were involved in the recent unrest. Images showing Taliban fighters driving in vehicles allegedly captured from the security forces have since been posted on social media.

Abdul Ahad Torial Kakar, a provincial councillor, said the situation would improve, but only after all sides had extorted more money from the poorest and weakest members of society.

“The oppression is not only being done by the militias,” he said. “It is being done by them all – the government and the insurgents – against the nation.”

foreign.desk@thenational.ae