ABU DHABI // Archaeologists have revealed the discovery of what they describe as one of the most remarkable and rare finds in the Gulf region – a 7,500-year-old, well-preserved three-room house.

The house was excavated on Marawah Island, just off the coast of Abu Dhabi, at what was once one of the region’s largest Stone Age settlements.

“These important discoveries signify Abu Dhabi’s advanced construction methods from the Neolithic [era] and the influential role it had in early long-distance maritime trade,” said Mohamed Al Mubarak, chairman of the Abu Dhabi Tourism and Culture Authority.

“The expertise of our team of archaeologists allows us to build a narrative of the emirate’s development and history, piecing together an intriguing and intricate story of the earliest known inhabitants of the emirate of Abu Dhabi.”

Abdulla Al Kaabi, TCA coastal heritage archaeologist, said radiocarbon dating of the deposit revealed the age of the house.

“This style of architecture is unique for this period and has never been found before in the region,” he said.

Dr Mark Beech, head of coastal heritage and palaeontology at TCA, said it was “very unusual” to find a Stone Age house “so well preserved that you have a complete plan of the structure”.

“It’s a stunning find because there are no parallels to it anywhere else in the Gulf coast region,” he said.

“You can see the back yard and small walls projecting out, which is where the cooking was carried out, just like traditional Arabian houses. We knew it was a Stone Age site but did not expect it to be so well preserved.”

The walls of the home are up to 70 centimetres wide, which enabled the residents to have corbelled walls, meaning they could build a dome shape by placing the stones on top of each other.

The site was excavated at one of seven mounds on the island.

Archaeologists predict that a complete Stone Age village could be unearthed.

“There are seven major mounds and we picked the smallest to excavate, so they potentially may have more than one structure,” Dr Beech said.

TCA said that artefacts found on the island had helped archaeologists piece together what life was like for these villagers.

They herded sheep and goats, and used stone tools to hunt and butcher other animals, such as gazelle. Small beads made from shell and a small shark’s tooth were also found at the site and had been very carefully drilled, leading archaeologists to believe they were probably worn as adornments.

One of their most significant finds, during previous excavations, was a decorated ceramic jar from Iraq – the earliest evidence of sea trade during that period.

“The recent excavations have clarified a lot of questions we had about this period,” Dr Beech said. “It tells us about life in the Stone Age and that people had domestic animals, but they also relied a lot on marine life.

“It also shows that they had a varied diet and were involved in long-distance trade, as we see with the pottery. Life on these islands was actually quite good.

“You had food resources, water supply and trade, and, of course, the climate was better than the present time.”

Villagers lived in a completely different setting, with freshwater lakes and more vegetation.

While the island is a marine protected site and not open to the public, some items could be placed on display at public museums.

“Material will gradually go on display but we are still studying, doing investigations and preparing publications,” said Dr Beech.

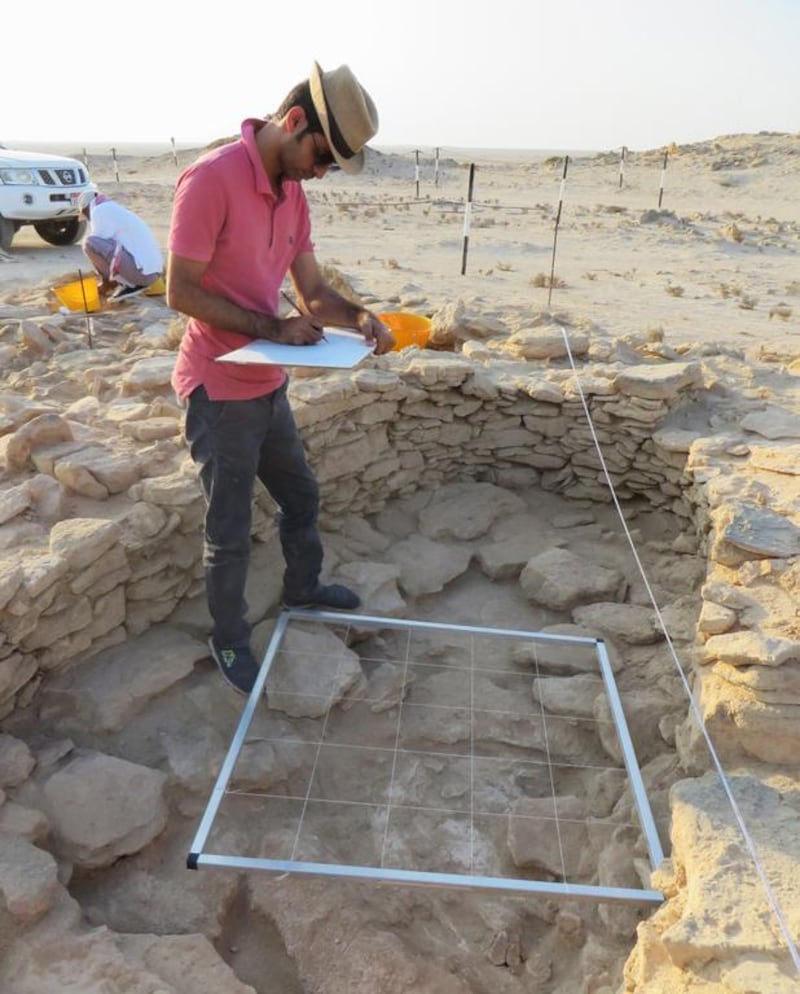

“Sometimes it takes many years of work to document a site because we have to be very careful, drawing maps, documenting, studying.”

The Marawah excavations will continue for many years because “it’s a slow, painstaking process of digging, screening and putting everything through a 1 millimetre sieve and sorting it”, he said.

New excavations at Baynunah, about 130 kilometres south-west of Abu Dhabi, have also revealed a different side of ancient life in the emirate.

The desert surface of the site is “littered” with white fragments of bones of ancient wild camels – the remains of animals that were hunted and killed 6,500 years ago, TCA said.

The site has provided the earliest evidence in the Middle East for the mass killing of wild camels. Research is being conducted on the near-complete skeletons that will allow experts to discover more about the biology of wild camels, TCA said.

salnuwais@thenational.ae