Just days before going to the polls for the second time this year, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu announced, to much fanfare on home turf, that he planned to annex the Jordan Valley region of the occupied West Bank should he secure another term in office.

It was a move intended to rally right-wing voters behind his party, Likud, which remains in close competition with the opposition Blue and White list. Having failed to form a government in April's election and with corruption charges looming over him, the stakes have never been higher for Mr Netanyahu.

Describing the reportedly pending peace plan of the US administration as an "historic opportunity", Mr Netanyahu said he would seek to "apply sovereignty in the communities and other areas" – the euphemistic language used to describe annexing settlements – in co-ordination with the US. In his crosshairs is one quarter of the occupied West Bank, where thousands of illegal Israeli settlers already live.

Yet even if Mr Netanyahu fails to emerge as head of a right-wing government after Tuesday's vote and the coalition talks which will follow, or ultimately ends up being forced out of politics on a criminal indictment, none of the possible outcomes of this election favour Palestinians.

With or without Mr Netanyahu, Likud as a party and its senior figures are opposed to Palestinian statehood, a policy of rejection shared by the main opposition list. One has only to observe how the Blue and White party’s response to Mr Netanyahu’s promise to annex the Jordan Valley was to accuse him of stealing their policy rather than condemning it altogether.

Blue and White, the main challenger to Netanyahu's left: annexing the Jordan Valley, seizing nearly thirty percent of the West Bank, and territorially encircling millions of West Bank Palestinians so that they can never have a border with Jordan...that was our idea first. https://t.co/rnfJNLqoKu

— Nathan Thrall (@NathanThrall) September 11, 2019

Appealing to his base, Mr Netanyahu is hoping to do what he failed to in April's election, when both Likud and the rival Blue and White party tied for 35 seats each: namely, to form a stable coalition government. Then, to thwart the possibility of opposition parties forming an alternative coalition, Mr Netanyahu opted instead to dissolve the Knesset and push for fresh elections.

Yet with just days to go, it remains unclear whether this election re-run will produce a drastically different result from the previous time, let alone a majority coalition for his Likud party.

The long-serving prime minister’s natural partners are parties further to the right, such as the Yamina alliance headed by former justice minister Ayelet Shaked, and the two parties representing the interests of ultra-orthodox Jewish Israelis, Shas and United Torah Judaism (UTJ).

According to the polls, however, Likud and its allies will struggle to cross the 60-seat threshold needed to form a majority in the Knesset.

This was, in fact, precisely the problem in April, when Mr Netanyahu found himself needing the support of right-wing former minister Avigdor Lieberman.

The Yisrael Beiteinu party chair, however, refused to budge on his demand that ultra-orthodox students do military service, setting up an irresolvable clash with Shas and UTJ.

With polls predicting a similar outcome to April, when Likud and the opposition list Blue and White secured just over a quarter of the Knesset’s seats each, the stage is set for Mr Lieberman to play the role of kingmaker.

For his part, Mr Lieberman is heading into the new elections calling for a unity government to include Likud, Blue and White and his own party, as a way of excluding ultra-orthodox factions from gaining power.

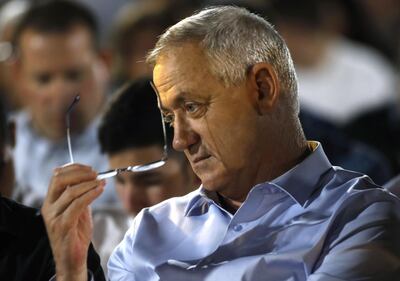

Meanwhile, Blue and White’s leader, Benny Gantz, a former head of the Israeli military, has declared that he will only sit in government with Likud if Mr Netanyahu is replaced as party leader.

Such a message resonates with many Jewish Israelis, for whom the looming corruption indictment faced by Mr Netanyahu means that Israel’s longest-serving prime minister is no longer fit for office.

Mr Netanyahu faces charges of bribery, fraud and breach of trust in three separate cases in which he is accused of offering favours in exchange for gifts, and promising privileges to media outlet owners in exchange for more favourable coverage.

A pre-trial indictment hearing will take place in early October, the last stage before Israeli attorney general Avichai Mandelblit can formally charge Mr Netanyahu. Although there is no obligation for Mr Netanyahu to step down when indicted, a sitting prime minister facing trial would be unprecedented.

Mr Netanyahu’s legal troubles are one of a number of factors that will shape this election and the coalition talks that will take place in its aftermath.

Turnout is hard to predict, with some suggesting that voter fatigue in an election-rerun could influence the results; a fall in turnout could have a particularly significant impact for the Joint List, the alliance of Arab-dominated parties, or for those parties hovering around the electoral threshold of 3.25 per cent of the national vote.

Failing to reach the electoral threshold spells lost votes for either the religious right bloc or the centrist bloc; the far-right Otzma Yehudit party, for example, might either give Mr Netanyahu another four or more seats for a coalition, or fail to reach the Knesset at all, which would mean squandered votes.

Meanwhile, the only thing holding the Blue and White party together – an alliance of convenience between Mr Gantz’s Israel Resilience, Yair Lapid’s Yesh Atid and Moshe Yaalon’s Telem – is opposition to Mr Netanyahu. Yet a plurality of voters still see Mr Netanyahu as most qualified to be prime minister.

With all these and other variables at play, there are, unsurprisingly, a few different possible scenarios that could emerge.

Mr Netanyahu’s ideal outcome would see Likud and its right-wing allies acquire more than 60 seats collectively, allowing him to form a new Likud-led government while providing him with the opportunity to try to pass legislation that would guarantee him immunity from prosecution.

Another – highly unlikely – scenario would see the Blue and White party, the Democratic Camp (Ehud Barak’s team-up with Meretz) and Labour-Gesher secure enough seats to form a minority government with the support – from outside the coalition government – of the Joint List.

However, a more probable outcome, based on current predictions, would see neither Likud nor the Blue and White parties able to form a coalition, under which circumstances Mr Lieberman could be in a strong position to negotiate a Likud-Blue and White unity government that includes Yisrael Beiteinu.

According to one poll, more than one-third of Jewish Israelis prefer a unity government headed either by Mr Gantz or Mr Netanyahu – a total of 39 per cent – compared to 32 per cent indicating they would prefer a right-wing government led by Mr Netanyahu.

Beyond those broad brushstrokes, further permutations are also possible, such as Likud deciding to ditch Mr Netanyahu in the context of forming a unity government with the Blue and White, or Mr Netanyahu tempting elements of the Blue and White party into a coalition government.

But what does all this mean for the Palestinians – and how will the election impact on the Trump administration's reported intention to reveal its political vision for the region?

If the Trump administration does indeed release a plan or the outline of one – and it's not impossible that the entire thing could be shelved, particularly now that one of its chief architects, Jason Greenblatt, has left office – the status quo experienced by the Palestinians under a colonial occupation will not change any time soon.

This, then, is perhaps the grimmest aspect of the new election. With no shortage of drama, subplots, and political intrigue, on the one issue that matters the most – the apartheid regime imposed on Palestinians – the election will ultimately make the least amount of difference.

Ben White is an author, journalist and analyst. His latest book is Cracks in the Wall: Beyond Apartheid in Palestine/Israel