Israeli leaders and others were livid at Palestinian president Mahmoud Abbas’s recent United Nations speech, which included the hyperbolic claim that Israel is guilty of “genocide” in Gaza. This unusually strong language from Mr Abbas was undoubtedly aimed at a domestic audience and designed to express the anger and frustration of Palestinians who seemingly have no viable strategy for moving forward towards national liberation.

Even though such remarks – including Israel’s own hyperbolic claims on social media recently that that “Hamas = ISIL” – aren’t helpful, they don’t actually change the strategic equation on the ground. They are, in both cases, snapshots of a political moment, and crucially one that can pass quickly without leaving a deep scar.

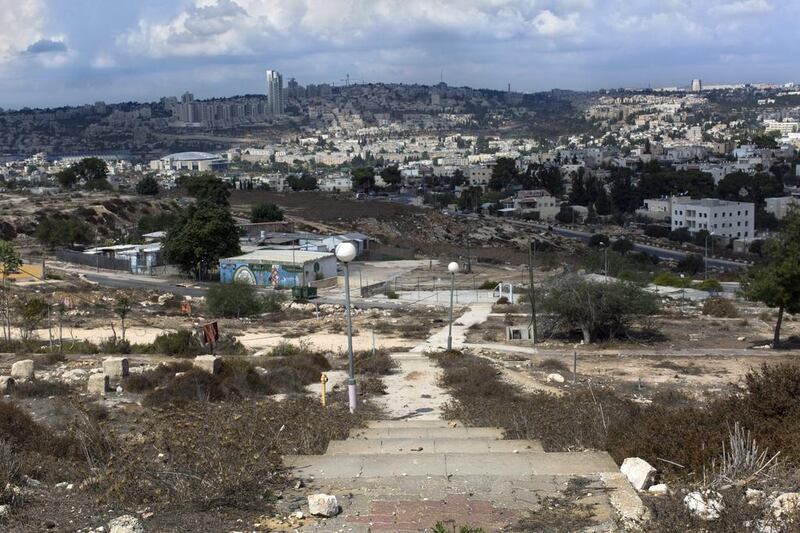

The same cannot be said for Israel’s latest announcement of impending settlement activity in occupied East Jerusalem. Plans for 2,610 new settler housing units were revealed last week in the so-called Givat Hamatos settlement, to the south of Jerusalem.

Building up this area would serve as another major feature of the strategic and demographic landscape, cutting key areas of Jerusalem off from the rest of the West Bank, particularly Bethlehem. It is closely linked with other highly controversial settlements known as Har Homa, which serve the same function, and will be the first entirely new Israeli settlement created in East Jerusalem since the development of Har Homa itself in the 1990s.

The new settlement, if completed, would be a major strategic blow to the potential for a two-state solution. It would make a reasonable compromise on Jerusalem, which is essential to any real peace agreement, more difficult to achieve. Moreover, like any major settlement expansion, it increases the Israeli constituency and vested interest against territorial compromise. Indeed, because it goes directly to the question of the future of Jerusalem, this new settlement is particularly provocative and damaging.

It sends the message that Israel is determined to keep hold of occupied East Jerusalem, and the areas around it. The timing is particularly bad because, following the war in Gaza, it was essential that the Palestinian Authority find a means of demonstrating that its approach of seeking a peaceful, negotiated, solution with Israel delivers results. Hamas is now claiming that its policy of armed struggle has been somehow vindicated by the recent conflict, even though comparatively little was gained for Palestinians or Gaza amid colossal destruction.

Yet Hamas at least can claim to have established agency, initiative and momentum. Israel’s latest settlement activity seems almost calculated to play into their hands. It certainly delivers another brutal blow to Mr Abbas and all those who seek a negotiated agreement. It undermines the credibility of potential negotiations, and of the negotiators themselves.

Hagit Ofran, the spokeswoman for the Israeli group Peace Now, correctly observed that “Givat Hamatos is destructive to the two-state solution. It divides the potential Palestinian state ... [and through it, prime minister Benjamin] Netanyahu continues his policy of destroying the possibility of a two-state solution”. If this is the reaction on the Israeli left, imagine how the move is playing among Palestinians.

The good news is it has met with a sharp rebuke from Washington as well. Following a meeting late last week between president Barack Obama and Mr Netanyahu, White House spokesman Josh Earnest launched an unusually harsh critique of Israel’s decision. “The United States is deeply concerned by reports that the Israeli government has moved forward with the planning process in a sensitive area of East Jerusalem,” he said.

Mr Earnest continued: “This development will only draw condemnation from the international community, distance Israel from even its closest allies, poison the atmosphere not only with the Palestinians but also with the very Arab governments with which prime minister Netanyahu said he wanted to build relations.”

His devastating conclusion was that “it would also call into question Israel’s ultimate commitment to a peaceful negotiated settlement with the Palestinians”.

Mr Earnest also strongly criticised moves by Israeli settlers to take over Palestinian buildings in the heavily contested Jerusalem neighbourhood of Silwan, which is reportedly the subject of a long-term plan of takeover by hundreds of Israeli extremists.

The criticism is welcome, but on its own it is insufficient. The United States and other key allies of Israel instead must move quickly to ensure that Israel does not, in fact, follow through on the plans for the new settlement. Numerous other highly damaging settlement plans have been put on hold in recent years because of American objections, which have proven their effectiveness when they are strong and consistent enough.

Sweden’s announcement of its upcoming recognition of the State of Palestine is significant, but not nearly as significant as blocking the new settlement activity. In the long run, Israel’s own future and security require a peace agreement with the Palestinians. So stopping Israeli fanatics from greatly deepening the hole in which they find themselves will actually be doing Israel a favour.

But even if many Israelis don’t see it that way, the international community is committed to a two-state solution. They must know that redrawing the infrastructural and demographic map, especially around the important area of East Jerusalem, is the gravest possible long-term threat to realising peace. It therefore has a responsibility, and the ability, to restrain Israel from its latest folly.

Hussein Ibish is a senior fellow at the American Task Force on Palestine

On Twitter: @Ibishblog