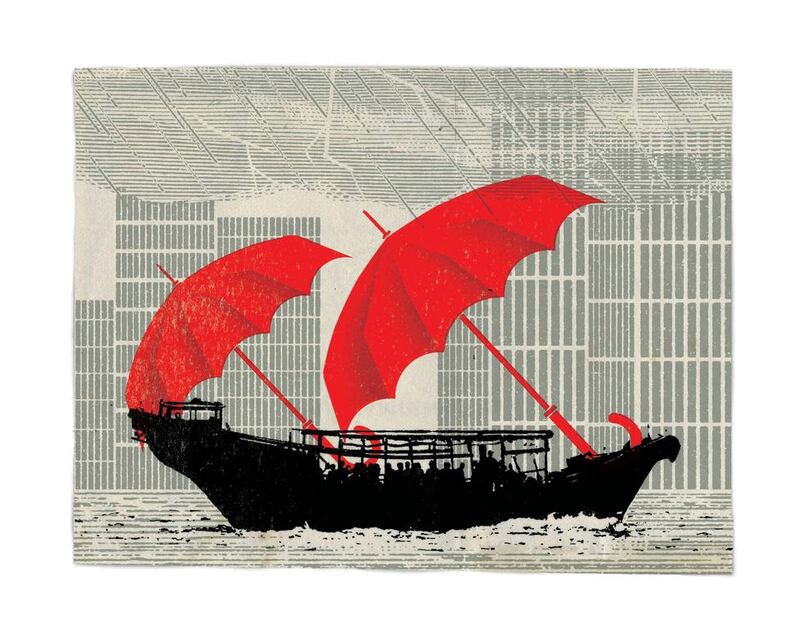

We’ve seen many emotions in the new wave of protest and occupation over the past few years. Fear. Rage. Desperation. But the student led occupiers of Hong Kong have brought something new to the protest party: enchantment.

That at least is the impression spread widely over social and conventional media of the scenes at Hong Kong’s main protest camp, which sprawls across an eight-lane highway at Admiralty, in the heart of the government district.

In one part of the camp, there’s a discussion on civil disobedience. In another, people are learning to make origami versions of the umbrellas for which the movement has been named. Instead of graffiti scrawled on walls, protesters neatly summarise their aspirations on post-it notes affixed to a “Lennon wall”. Now and then, everyone stops to pick up litter. There is a well-appointed women’s toilet and a charging station for electronic devices. Proposals are put forward by the recognised leadership and are solemnly discussed by the crowd. There is an altar for those who wish to pray to the Christian deity and a mini-temple to Guan Yu, Taoist god of justice, for those who prefer something more traditionally Chinese. A row of tents is neatly stencilled with numbers, for the convenience of postal workers. Many of the reporters at the scene shake themselves and go off to try to write something objective. But it’s obvious that they are completely and utterly charmed by the whole experience.

There’s no doubt that the occupation is an accurate reflection of the personalities involved. The whole thing is “very Hong Kong” and specifically, very young Hong Kong: earnest, impish, sweet-natured, well-mannered, idealistic and sentimental. This is a movement whose best known anthem – Do You Hear the People Sing – is a selection from the stage musical of Les Miserables.

The Admiralty camp also embodies a rigorously thought-out political strategy by a seasoned group of young political campaigners, working off the back of a successful mass mobilisation to prevent “patriotic education” being imposed on the Hong Kong curriculum. The camp doesn’t just exist to push forward the protesters current demand for full democracy in Hong Kong. It embodies the kind of city they want to live in. It is designed as a small-scale civil utopia.

Most of all, it leverages the physical vulnerability of the protesters into a strength against the forces of law and order. Even the sight of many members of the not especially paramilitarised Hong Kong police in proximity to the camp makes onlookers want to stretch out a protective arm.

The protesters’ vulnerability has in fact been re-engineered as a force multiplier. On an average day, attendance does not exceed a few hundred, with crowds swelling in the evening, after part-time supporters are done with work or school. But numbers grow at moments of crisis and at any time the camp is believed to be under threat from the authorities. The effect is to make the camp untouchable, at least for now.

The atmosphere at the other main protest site at Mong Kok is different. There, the crowd is a little older, tougher and angrier – tougher in middle-class Hong Kong terms, that is, which is to say it is composed of people you would be perfectly happy to meet down a dark alley. Nonetheless, clashes between protesters and police are more frequent there. So are slanging matches between occupiers and counter-demonstrators. Hard hats and gas masks have begun to replace umbrellas as the signature accoutrement of the people on the street.

It may be that the authorities are engineering a constant round of clashes in Mong Kok precisely because they want to shift the public gaze to a location where, if you squint hard enough, you can see something that looks like a more conventional riot control scenario. Indeed, organisers at the Admiralty site have called more than once for the Mong Kok occupiers to stand down, with no success. If Mong Kok falls, say protesters at the site, Admiralty is next. Again, the protective impulse is at work.

It’s all very impressive. But it leaves the question open of how so many young people in Hong Kong came to successfully adopt the organising techniques of anarchists. How did people so young get to be so good at protest? The conventional answer is that it all stems from misgovernment after the 1997 handover to China. This is true, but only part of the truth. Protest has a much longer history in Hong Kong.

In 1967, ironically enough, students were prominent in the pro-Beijing demonstrations that descended into extensive rioting. But the emergence of civil Hong Kong can perhaps be better dated to the mass anti-graft protests of 1973. At that time, Hong Kong was deeply corrupt. So called “tea money” was charged for almost every transaction, from getting a bedpan in hospital to ensuring that firefighters actually turned on their hoses.

The protests of that year led to extensive civil service reforms and the establishment of the highly effective Independent Commission Against Corruption. But perhaps more importantly, it also enabled Hong Kongers to free themselves from the miasma of corruption, make over local institutions and professions and rebuild the city’s reputation to be one of honesty and integrity. In politics, it marked a beginning of a long, obdurate and partially successful struggle for democratic rights and practices, a struggle begun against the oligarchy that represented the interests of colonial London and now continues against the oligarchy that represents the interests of neocolonial Beijing. Contrary to the myth of the apolitical, business minded metropolis, protest is an integral part of the Hong Kong identity. People have been protesting in Hong Kong for so many years that it should not be a surprise when even the children become good at it.

There’s a strong case to say that they have become better at it than their elders. When Beijing announced its plans to impose political vetting on candidates for Chief Executive, the official Occupy Hong Kong with Love and Peace Movement backed down. The current occupation grew out of a class boycott organised by high school and university students.

The Hong Kong establishment had hoped to turn the local electorate into a kind of giant rubber stamp for whichever leader was approved by Beijing. After a long drawn out and entirely bogus consultation exercise, they counted on Hong Kongers being so sick of the whole subject that they would let this decision pass without much visible dissent.

And if it wasn’t for those pesky kids they might just have got away with it.

Jamie Kenny is a UK-based journalist and writer specialising in China