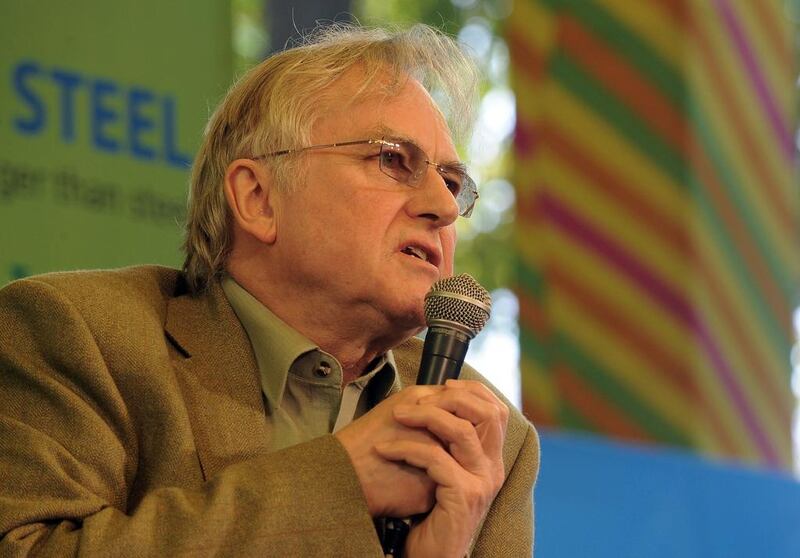

There was a time when the British scientist Richard Dawkins was widely admired. The former Charles Simonyi Professor for the Public Understanding of Science at Oxford University was lauded for his work on evolutionary biology, about which he wrote international bestsellers, and was showered with honours at home and abroad.

More recently, he has shifted his attention to religion and has become known as one of its fiercest opponents. His insistence on allowing for none of the shade and subtlety that characterise the works of scholars such as Karen Armstrong, author of acclaimed books on Islam and the history of the monotheistic religions, have offended and infuriated millions. But they also have thrilled his followers who wish all discussion of faith to be banished to the fringes of the public square.

Mr Dawkins has always been pugnacious. When I interviewed the philosopher Daniel Dennett, a professor at Tufts University and a fellow leading member of an atheist group that calls itself the Brights, he described himself as being the “good cop” to Mr Dawkins’s “bad cop”. Mr Dennett conceded: “Richard is so hostile and aggressive that he’s unsympathetic.”

But now, Mr Dawkins’s unwillingness to treat anyone who disagrees with him as though they had even half a functioning brain cell is putting off even his own supporters.

“Richard Dawkins, whatever happened to you?” read a recent headline in The Guardian, the British newspaper whose readers and staff are generally among the most sympathetic to him. What does it say when a home to some of the most ardent atheists wants Richard Dawkins, frankly, to put a sock in it?

This is not about the question of whether he has any real authority to lecture on religion and philosophy, although that is a very legitimate point. “Imagine someone holding forth on biology whose only knowledge of the subject is the Book of British Birds, and you have a rough idea of what it feels like to read Richard Dawkins on theology,” wrote the distinguished literary critic Terry Eagleton in his review of Mr Dawkins’s The God Delusion in 2006.

The issue is more about the arrogance of his certainty, and the frequent and public manner in which he declares his great “truths”.

It is worth pointing out here that Mr Dawkins and his battalions of aggressively self-proclaiming atheists – as opposed to those who see no need to label those of faith as suffering from “a kind of mental illness”, as he has put it – are in a tiny minority.

The Malaysian opposition leader, Anwar Ibrahim, once said that South-east Asian man was “homo religious” – and the same applies across all Asia, Africa and pretty much the whole planet, with the exception of small liberal elites and, to a larger extent, in a Europe that has become at least partially post-Christian.

On a trip to Kenya to write about an inter-faith project between Catholics, Anglicans, Muslims and Pentecostalists, I asked a local worker about the percentages of the population who followed the different faiths. When I asked what number were atheists, she looked at me as though I was mad.

Being in a minority doesn’t mean you are wrong, of course, but this is the reality of the world in which Mr Dawkins is railing. For him to show just a little respect for the genuinely held beliefs of billions throughout the entirety of human history ought not to be too much to ask.

It evidently is, though. And this certainty extends to his view on how we should think. His most recent foray into controversy – or perhaps I should say, given the subject matter, his latest attempt to stoke controversy – was over some tweets arguing that “Mild paedophilia is bad. Violent paedophilia is worse. If you think that’s an endorsement of mild paedophilia, go away and learn how to think.”

He then followed this up by making a similar comparison about different kinds of rape, with the same lecturing injunction about going away and learning how to think.

Mr Dawkins’s intelligence is beyond doubt, and by all accounts he is personable, erudite and cultured. But a man so encased in the rigid logic of his position that he cannot see how presumptuous it is for him to make statements that suggest the victims of sexual abuse should bear in mind his graduating scale when gauging their trauma is one who has lost sight of all those aspects of humanity that do not fit onto his desiccated scientific calculating machine.

Where are the places for emotion, culture, custom, tradition, for so many of the responses – non-rational, perhaps – that nonetheless make up so much of the warp and weft of our lives and our attempts to make sense of a universe that is beyond complete human comprehension?

After his latest comments caused a huge backlash, Mr Dawkins said he had learnt that “there are people on Twitter who think in absolutist terms, to an extent I wouldn’t have believed possible”. His tragedy – his delusion, one might say – is that he does not appear to realise that his own dogmatic and highly aggressive attacks on much that many hold so dear, including religion, lead him to come across as far more absolutist than any of the critics to whom he condescends to reply.

Intolerant, angry, petulant: no wonder even atheists think Mr Dawkins has gone too far this time.

Sholto Byrnes is a Doha-based commentator and consultant