The shooting of three American Muslim students in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, this month has focused attention on anti-Muslim hatred in the US.

There are strong reasons for thinking the suspect, Craig Stephen Hicks, was motivated by anti-Muslim animosity to murder Deah Barakat, 23, Yusor Abu-Salha, 21, and Razan Abu-Salha, 19. The FBI is now investigating the case as a possible hate crime, although initial reports stated the murder may have been about a dispute over parking.

In 2011, I spent a year travelling around the US investigating anti-Muslim prejudice. In a suburban restaurant in Houston, I saw a poster that perfectly captured the nature of the problem. The restaurant owner had used a photograph of a lynching in the early 20th century, featuring a tree, a dead body hanging from a branch and a crowd of white people in the foreground looking jubilant. In place of the black victim of the original image, the face of a stereotypical Arab was superimposed with the caption: “Let’s play cowboys and Iranians.”

It was a disturbing sight. In the same neighbourhood, I had heard stories of teenagers beaten up at school simply for being Arab, of harassment of mosque congregations and of death threats against Muslims aired on local radio stations. It was also disturbing because racist imagery appeared to be a perfectly normal way to decorate a restaurant. But the image was also revealing because it shows anti-Muslim sentiment in the US is part of a longer racial history.

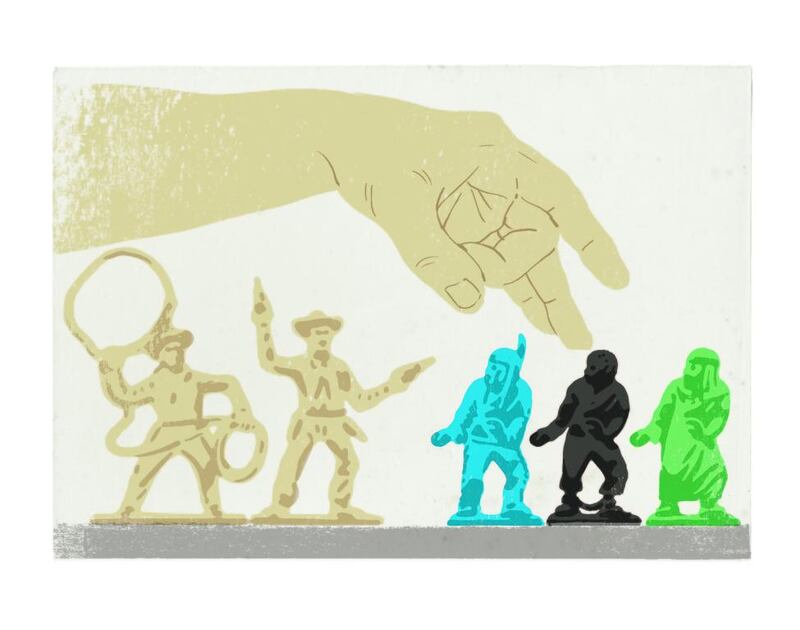

The poster’s caption played on the phrase “cowboys and Indians” and was an implicit celebration of the genocide of America’s indigenous peoples by European settlers, the first act in the racial history of the US and one that continues to haunt an American culture obsessed with enemies at its frontiers.

Likewise, the use of a photo of a lynching ties its meaning to the history of racial segregation after the abolition of slavery, and the ways that violence was used to maintain white supremacy.

Anti-Muslim prejudice is the most recent layer in this history, a reworking and recycling of older logics of oppression. From this perspective, Islamophobia, like other forms of prejudice, should not be seen only as a problem of hate crimes committed by lone extremists. The acts of individual perpetrators can only be made sense of if they are seen as the product of a wider culture, in which glorifying racial violence is acceptable.

All empires require violence to sustain themselves, and the violence perpetrated overseas by imperial powers always flows back, in one form or another, to the “homeland.” In modern times, that violence also always takes on a racial character.

The British Empire relied upon racist ideology to maintain its authority, both domestically and in colonial settings, and particularly in the face of resistance to its rule. Blacks and Asians from the colonies who settled in Britain after the Second World War encountered the racism imperialism had fostered there, persisting long after the British Empire itself no longer existed.

Since the end of the Cold War, US foreign policy planners have regarded the Middle East as their most troublesome territory, where resistance seems to be especially strong against the US’s key regional ally, Israel. Large sections of the US political and cultural elite have turned to racial ways of explaining resistance to its authority. Rather than see the Palestinian movement, for example, as rooted in a struggle against military occupation and for human rights, it has been more convenient to think that Arabs are inherently fanatical. In other words, the problem is their culture, not our politics.

With the War on Terror, that rhetoric was generalised to Muslims as a whole: the religion somehow especially prone to terrorist violence. The US government’s own violence – torture, drone strikes, and military occupations, which result in many times more deaths than “jihadist” terrorism – can then be more easily defended.

Take, for example, the popular US writer Sam Harris, one of the so-called new atheists who seem to have influenced Craig Hicks in Chapel Hill. Harris has said that “Islam is the mother-lode of bad ideas” and that “we are misled to think the fundamentalists are the fringe”. He claims human rights problems in what he reductively calls “the Muslim world” are caused by Islam, as if it is a monolith that mechanically drives followers to acts of barbarism.

But beliefs reflect social and political conditions as much as they shape them. Global opinion polls suggest that whether one thinks that violence against civilians is legitimate, for example, has more to do with political context than religious belief. Such violence is considered more acceptable in the US and Europe than everywhere else in the world.

Indeed, Sam Harris himself has written in support of killing civilians for the beliefs they hold. In his book, The End of Faith, he says that “some propositions are so dangerous that it may even be ethical to kill people for believing them”. He maintains this is what the US attempted in Afghanistan.

“It is what we and other western powers are bound to attempt, at an even greater cost to ourselves and to innocents abroad, elsewhere in the Muslim world,” he wrote. “We will continue to spill blood in what is, at bottom, a war of ideas.”

In this argument, religious belief becomes a proxy for imminent threat in order to justify wars of aggression against a population defined by its religion.

His argument not only provides rhetorical support for wars that have led to the deaths of at least half a million people since the attacks of September 11, 2001, but also gives a rationale for acts of Islamophobic violence at home. Since 2001, dozens of people have been killed in the US by right-wing extremists who have absorbed the racist logic of American imperialism – more than by the “jihadists” regarded as the chief threat of terrorism.

However the online response to the Chapel Hill murders shows there is also another America – one that recently took to the streets to protest against police racism with the slogan #BlackLivesMatter. (This month, the slogan #MuslimLivesMatter also began to trend on Twitter.) For this other America to overcome the US’s long racial history, it will need to understand that Islamophobia is more than the hatred of a small number of individuals, but a system of violence and oppression, inherently connected to imperialism.

Arun Kundnani is the author of The Muslims are Coming! Islamophobia, Extremism, and the Domestic War on Terror and teaches at New York University