I grew up reading Nabil Farouk’s Rewayat Masreyya Lel Geb (Egyptian Pocket Novels), particularly Ragol Al Mostaheel (The Man of the Impossible, the Egyptian version of James Bond) and Malaf Al Mostakbal (The Future File, a science fiction series) published in Arabic by the Modern Arab Association.

Such series were very popular in the region during the 1980s and 1990s. I can fairly say that those books contributed greatly not only to my love of reading, but also to my Arabic language development. I still remember my indulgence in these fictional worlds and fictional characters, which introduced me to many words and phrases that I would not have learnt outside these books.

Unfortunately, such options don’t seem to be available for children nowadays. The limited choices of Arabic books for young people, particularly in genres like fantasy and science fiction, was discussed during the 2015 Emirates Airline Festival of Literature last week.

Noura Al Noman, an Emirati science fiction writer of Ajwan and its sequel Mandaan, expressed her disappointment at the situation. She told the audience that she was motivated to write novels after she was unable to find young adult science fiction in Arabic for her daughters to read. She noted that the number of Arabic teenage fiction books in all genres is very small, not only in science fiction, and encouraged authors to target this particular age group.

Another important point that should be discussed is that the available Arabic fiction has not caught up with the latest technological advances, including audiobooks and podcasts.

But even if more books were available in Arabic, there are no guarantees that young people would actually read or listen to them, especially with the great level of competition in the market?

These days, there are many other entertaining options for young people, including TV shows, video games and the internet. Most of the best content in these is in English.

Children are nowadays exposed to English content in far more fun and interesting ways in both physical and social-media environments. In these circumstances, it’s not surprising that children have no strong motivation to learn Arabic.

Take video games, for example, which are very popular among young people in the UAE and elsewhere. Children spend substantial amounts of time on PlayStation, Xbox, Nintendo, Wii and computer gaming. Younger kids also spend a long time on gaming applications on their iPads and other tablets. But how many of those video games and applications support the Arabic language?

Another important example is TV shows. In my view, the Arabic TV series, particularly the Khaleeji ones, focus mostly on social drama, discussing the same issues over and over again. It’s no wonder English TV series are more popular in the region. They provide a variety of genres and present a range of stories in a more realistic and engaging way. Not to mention the quality of production.

English language films (particularly from Hollywood) are also more popular, not only here in the UAE, but worldwide. However, in some countries including France and Germany, these movies are available in the local language. So people go to the cinema and watch them dubbed into their own language.

Furthermore, English is the dominant language online; more than half of the internet’s content is in the English language. Arabic content does not exceed 3 per cent of the total.

We need to keep all these factors in mind when we discuss the weakening role of the Arabic language.

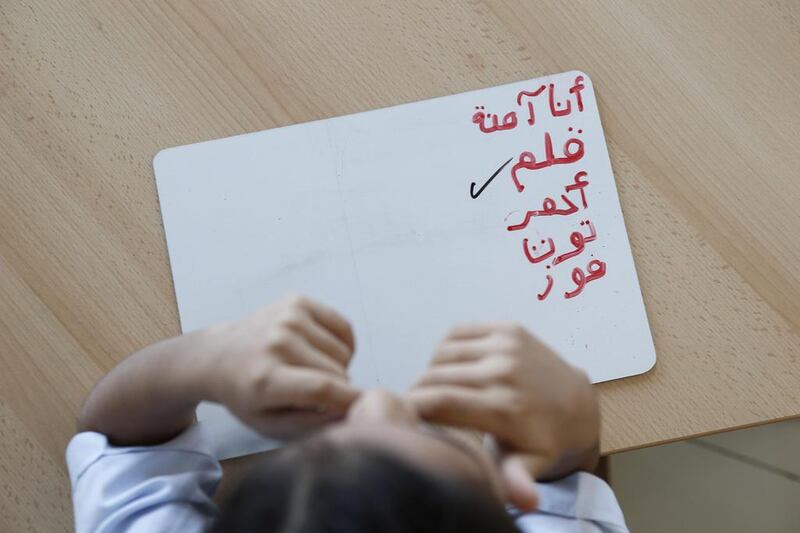

In a special report by The National, experts said that Arabic was at risk of becoming a foreign language in the UAE, where many pupils complete their education with poor speaking and writing skills.

The report focused on the role of education institutions in addressing the issue.

Indeed, there is an urgent need to address Arabic pedagogy issues. School curriculums need to catch up with sophisticated language learning techniques.

There is also a need to improve the quality of Arabic teachers and work on finding and producing a wide-range of interesting learning resources for students.

While the debate mostly focuses on how the language is being taught in schools, there is also a need to make learning Arabic relevant in young people’s daily lives. Also, we must stop blaming the English language, because doing so will only distract us from focusing on improving the Arabic content.

aalmazrouei@thenational.ae

@AyeshaAlmazroui