Entering Gaza feels a little like infiltrating the world’s largest prison, home to 1.8 million inmates, living on 360 square kilometres of land. Small, impoverished, overcrowded and trapped between the sea and the Israeli-Egyptian blockade, Gaza is a stifling and suffocating place.

Already confronted with a severe housing shortage before the Israeli military offensive in 2014, the displaced live in whatever spaces are available: United Nations Relief and Works Agency schools, tents, heat-intensifying tin-plate or zinc containers, even in damaged buildings.

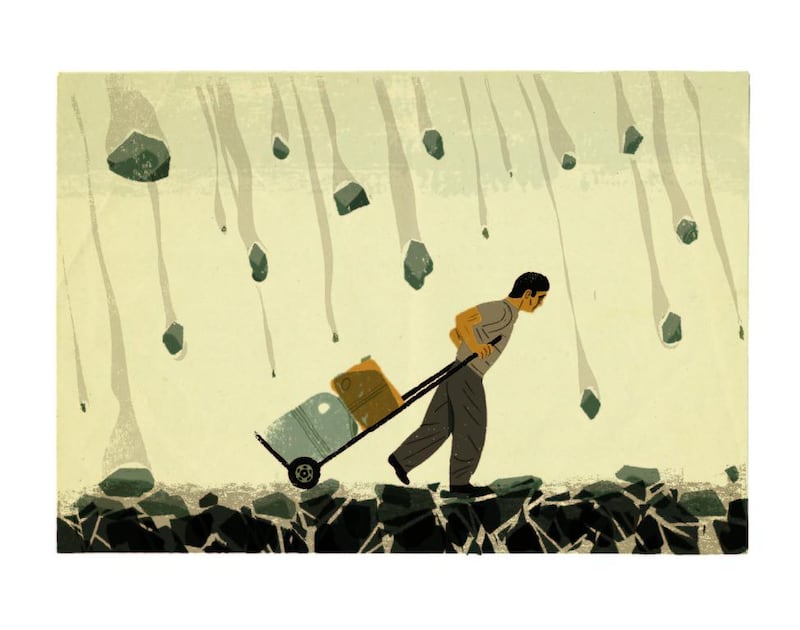

With reconstruction work stalled for the lack of materials and funds, the deep scars left on the landscape by last summer’s brutal war have not even begun to heal. The ruins of war are visible almost everywhere, even in Gaza city’s only upmarket neighbourhood, Al Rimal.

The Shuja’iyya district, which was flattened by Israeli forces, is still largely a rubble-strewn crater. Bulldozers slowly remove the traces of destruction and young children play in the newly vacated spaces, asking us to take their photos.

It is not just the landscape and architecture that are scarred. Gaza is an emotional wreck following last year’s war in which 2,100 Palestinians and 66 Islraeli soldiers died .

“There is a high level of psychological pressure in the Gaza strip,” says Hasan Zeyada, a veteran psychologist at the pioneering Gaza Community Mental Health Programme.

Beneath the Gazans’ smiling, welcoming facades, you find bubbling despair and overwhelming distress. “This is no life. No one cares about us,” says Samer, a teenager forced to collect and sell rubble to help his now-homeless family.

With large families the norm, people seek whatever escape they can. Gaza’s teeming beaches are popular day and night, even in areas where raw sewage flows straight into the sea.

“We go to sleep, we wake up, we take walks on the beach – we fill the time,” says unemployed graduate Saleh Ashour, 24, describing a typical day.

Everywhere you turn, there are many, many children, but few genuine childhoods are visible. With the exception of flashy, brightly lit toy cars on the beach promenade and a few makeshift football pitches, there is little in the way of child’s play, but a rising amount of child labour. And these poor young souls, who make up the majority of Gaza’s population, are the most vulnerable psychologically. “Children are the most sensitive group and they are the most likely to be affected by the sociopolitical reality,” explains Dr Zeyada.

And the trauma some have endured could buckle the toughest adult’s shoulders. Take Reda, 15, who lost her mother, several siblings and members of her extended family during an Israeli airstrike. Now she must care for her father and surviving siblings, while clinging desperately to the memory of her mother. “My mum was my friend … I feel that she is talking to me,” the girl told Al Mizan, a Gaza-based human rights organisation. Reda has shed 8kg, her appetite drained by dreams of eating the pizza her mother was preparing when the airstrike happened.

The trauma of loss has been tough on the adult population too. “I lost Arwa, the apple of my heart,” says Hamida, whose favourite niece perished with 18 other members of her family. “When I used to visit her, her smile would precede her and she would open her arms wide to hug me … Her drawings were so beautiful. I wish one had survived.”

But it is not just the trauma of war and the loss of loved ones that afflicts Gaza’s adult population. There is also the immense psychological impact of Gaza’s long isolation, which has, according to World Bank data, led to an unemployment rate of 44 per cent (60 per cent for youth), GDP at a quarter of what it could be without the blockade and real per-capita income a fifth of what it was two decades ago.

“The whole of life in Gaza is in a state of deterioration. There is no stability for anyone. Gaza has endured multiple losses, what we call multi-traumatic losses,” said Dr Zeyada, who became the patient as well as the doctor when he lost his mother and five other close family members during an airstrike. “People in other places usually endure a single loss: the loss of a home, or a family member, or a job. Many Gazans have lost them all.”

The prolonged and continuing stress and trauma have resulted in a plethora of difficulties, including low self-esteem, self-blame, displacement of anger, anxiety, panic attacks, impotence, obsessive compulsive disorders, mood swings and full-blown depression.

Displaced feelings of anger and frustration have also led to a growing level of domestic violence and more aggressive public behaviour, Dr Zeyada notes.

“I’m sitting around, and this guy’s sitting around, and that guy. We’ve all had it up to here,” says Ashour. “If someone comes and cracks a joke with me, I find I get all serious with him.”

Faced with this economic, social and psychological wasteland, large swathes of Gazan society are possessed with the overwhelming urge to take flight and escape. “If they open up the crossing and give us opportunities to emigrate, not a single young person would remain in Gaza, not even those with jobs,” says unemployed graduate Amer Teemah, 24. And true enough, even successful Gazan academics and journalists I met want to leave – temporarily, they say, but they fear they may decide never to return.

Teemah and his lifelong friend, Ashour, paid $3,500 (Dh12,850) each to smugglers to get them to Europe, but failed.

“You are condemned to be a failure before you can even start,” says a crestfallen Teemah, who has no clue what to do now that his outlandish plans to build a new life in another land have only landed him in debt.

Yet Gazans are remarkably tough and resilient survivors. Thousands continue to work, despite not having received a salary in months, and there is an air of relative law and order, considering the dire circumstances.

But if the status quo continues, Gaza faces the prospect of total psychological ruin, with unforeseeable consequences. Ultimately, Gaza’s psychological and emotional malaise is of an entirely man-made nature. “Many of the psychological problems in Gaza are reactive; they are a reaction to the present situation,” says Dr Zeyada. “That means that mental health in Gaza is connected to the political reality.”

Catastrophe can be averted if the blockades are lifted. That will provide the Gazan people with what they desperately miss the most: hope for the future.

Khaled Diab is a Belgian- Egyptian freelance journalist

On Twitter: @DiabolicalIdea