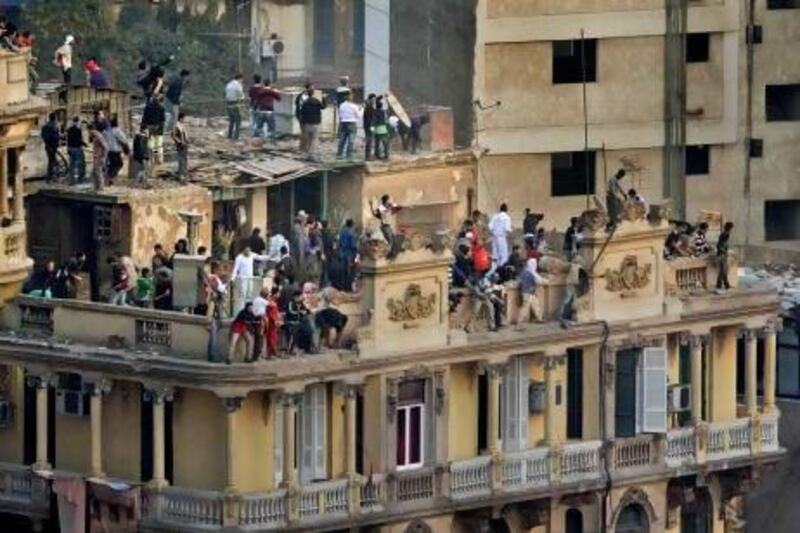

When those loyal to the regime of Hosni Mubarak besieged Tahrir Square on February 2, two and half years ago, charging through the crowds on camel and horseback, Egyptians battled side by side to defend their revolution. "The future of the Arab world, perched between revolt and the contempt of a crumbling order, was fought for in the streets of downtown Cairo," Anthony Shadid reported for The New York Times that day - and his words didn't sound like hyperbole. Shadid, who died a year later from an asthma attack while sneaking out of Syria, scrambled around central Cairo with "a dentist in a blue tie who ran toward the barricades", "a veiled mother of seven who filled a Styrofoam container with rocks" and "a 60-year-old grandfather, [who] kissed the ground before throwing himself against crowds mobilized by a state bent on driving them from the square."

Members of the officially banned but long-tolerated Muslim Brotherhood fought too alongside Egyptians now regarded as their political opponents. On February 2, at the so-called Battle of the Camel, Shadid noted that one protester's "description of the uprising as a revolution suggested that the events of the past week had overwhelmed even the Brotherhood, long considered the sole agent of change here". With hindsight, that line seems overstated. Or, rather, if the initial uprising outpaced the Brotherhood, the group caught up with events, seizing its chance, long sought, for political power in Egypt.

The Middle East's oldest Islamist organisation, and the most significant opposition within Arab states, the Muslim Brotherhood, has re-emerged out of the upheavals stirring the region. They may share a name, but the Syrian and Egyptian Brotherhoods have different histories that have altered each inextricably, creating Islamist organisations with very different stakes and roles in their country's struggles.

In The Muslim Brotherhood: Evolution of an Islamist Movement by Carrie Rosefsky Wickham, a densely packed, commanding study of the Brotherhood's long history - framed as a comparative analysis across Arab states, but really a book about the ideological and political development of the original branch in Egypt - the author also focuses on the Brotherhood's role in those 18 days of protest. Wickham cites a protester at the Battle of the Camel who was given "an impromptu lesson" by a Brother on the use of a slingshot. "I didn't like how aggressive the Brotherhood was," the protester says, "but I have to admit that they were more organised and ardent and their efforts were very important in protecting the square."

Before Morsi's overthrow, following the protests of millions calling for his resignation and the military's intervention, events such as these underscored the contradictions and pitfalls of the Brotherhood in power. The slingshot lesson symbolised both the Brotherhood's political organisation and electoral skills - and the ill will that engendered. Egypt's first civilian president alienated so many because he conformed to the clique mentality of the 90-year old Islamist organisation of which he was a ranking bureaucrat. Liberals, secularists and Islamists alike voted for him in the narrow second round run-off of the presidential election, some casting votes not in support of him but to keep Mubarak-era Ahmed Shafik from winning the presidency. Yet Morsi governed only to his conservative, often reactionary base, most obviously when he seized unchecked powers by unilateral decree in November 2012, putting himself and an Islamist-dominated constituent assembly (its non-Islamists having quit in protest) above judicial review so it could force through a hastily drafted constitution that secured Islamist ideals of social conservatism. It was exactly the kind of divisive absolutism that the Brotherhood's most fervent opponents feared.

The move didn't only outrage a swath of society; as recent reporting reveals, it brought together a crucial alliance between Mubarak-era business and security elites, the military, and the political opposition of the National Salvation Front. But as he did during the run-up to the June 30 protests, when the Tamarod or "Rebellion" campaign claimed to collect 22 million signatures calling for the president to resign, Morsi underestimated the extent of public anger, the power of still-intact regime institutions like the military and the police, and the fragility of his much-promoted democratic legitimacy. His rambling, defiant speeches - reminiscent of Mubarak's, only longer, with more finger-wagging - might have rallied his supporters, but to everyone else they projected only hubris.

Wickham's book ends well before the military deposed Morsi, but her analysis of how younger members of the Brotherhood courted political compromise and accommodation, only to be stamped out by the domineering old guard, can be extended to the recent upheaval. By her account, the steps Morsi took that led to his downfall reflect some of the organisation's historically familiar habits. "When the Brotherhood's vital interests are at stake and the opportunity exists to realise them," she writes, "the group's impulse toward self-assertion may trump its impulse toward self-restraint."

Although Wickham's account ends in the summer of 2012 after Morsi's election - the constitutional crisis at year's end would have made a revealing postscript - she proves prescient: "In order to push the transition in the direction it favours," she writes, "the Brotherhood may throw caution to the wind at critical junctures and deal with the fallout later." But the fallout came quickly: ousted from power altogether, and thrown back in jail by the military.

Within hours of the coup in Cairo, Bashar Al Assad was gloating in Damascus. "What is happening in Egypt is the fall of what is known as political Islam," Syria's president told a state-run newspaper. Assad's statement echoes regime rhetoric from the uprising's beginning, linked to Baath party bombast before the era of his father, Hafez. "We've been fighting the Muslim Brotherhood since the 1950s and we are still fighting with them," Assad had proclaimed in an earlier interview barely six months after the initial crackdown on peaceful protests in Deraa in 2011 that led to the devastating civil war. Calls by the Syrian government for Morsi to step down and honour the people's demands were more than cynical politicking from an autocratic regime fighting for its own survival. The fall of Egypt's Brotherhood president plays into Assad's language of self-preservation.

As Raphaël Lefèvre writes in his timely and essential history, Ashes of Hama: The Muslim Brotherhood in Syria, the frame of violent Islamism versus secular pan-Arabism – promoted as the exclusive domain of the Baath Party – has long offered successive Syrian regimes, even before the Assads, a narrative of legitimacy. Baathist ideology is rooted in claims to Arab modernity and secularism, defined by its opposition to political Islam in the form of the Brotherhood, which it demonised, fought bitterly, and then effectively exiled. “The rebels’ uncompromising demand for the overthrow of the regime,” Lefèvre argues, is tied to the long, bloody history of conflict between the Baath Party and the Muslim Brotherhood in Syria. Chants that “the people want the fall of the regime!” in the spring of 2011 competed in Syrian cities with another slogan: “We will not let the massacres of 1982 be repeated!” Or, as one rebel shouted: “Hafez died and Hama didn’t! Bashar will die and Hama won’t!” The massacre in Hama in 1982 ended the nearly six-year Brotherhood-led insurgency against Hafez Al Assad; the historic Orontes River city was levelled, over the bodies of as many as 40,000 fighters and civilians. As another rebel in Damascus in the current civil war insists: “The revolution started a long time ago, when my brother was arrested. He was part of the Muslim Brotherhood’s revolution in 1980.”

Seeing revolt against the regime or repression of the rebels as the final stage in a long, existential struggle is key to understanding the stalemate in Syria today and the Brotherhood’s role in it. For decades since Hama, the Baathist regime “enjoyed a free hand to caricature its most influential competitor”, Lefèvre writes. The fractured Brotherhood was deprived of credible, let-alone moderate leaders, and for many Syrians it became the bogeyman. This might sound like the Mubarak regime’s portrayal of its Islamist opponents, but as Lefèvre highlights, the Syrian Brotherhood is not simply a branch of the Egyptian movement. His book’s great strength is the way in which it sets the Syrian story of the Brotherhood in the context of the place, firmly rooted in the country’s tumultuous, often violent post-colonial history.

*****

In 1933, two young Syrians, Mustafa Al Sibai and Mohamed Al Hamid, went to Cairo to study at Al-Azhar University, where they met Hassan Al Banna, who had founded the Muslim Brotherhood five years before. He brought the two Syrians into the organisation, at the time a kind of religious social club devoted to the belief that a comprehensive return of religion to politics would revive and ultimately liberate Muslim societies dominated by foreign powers – whether the British in Egypt or the French in Syria. When Al Sibai and Al Hamid returned to Syria, they unified several jamiat or revivalist religious clubs that had formed in Damascus, Aleppo, and other cities in the 1920s and 1930s, where men debated how to advance the teachings of recent Islamic reformists such as Mohammed Abduh and Jamal Ad Din Al Afghani. Though he held an inaugural congress in 1937, Al Sibai, who became the head of the group, waited until 1945, with the French on the verge of their colonial withdrawal, to officially announce it as the Muslim Brotherhood.

While Syria’s postcolonial path was arguably the most unstable in the Middle East – a series of coups followed its independence in 1946, including three in 1949 alone, with 21 different governments by the time Hafez Al Assad seized power in 1970 – it nevertheless had a relatively functional parliamentary system that reflected a diverse Syrian polity divided as much between city and countryside as between religion and sect. Such context is crucial, Lefèvre writes: “In contrast to its Egyptian sister, the local Brotherhood would embrace early on the game of politics in its contemporary sense – abiding by the rules of parliamentary democracy, forming political parties and engaging in compromises.”

Al Sibai was elected to parliament in 1949, and two more Brothers were made ministers in government. Lefèvre believes such participation shows how the Brotherhood in Syria "was a political force willing to display pragmatism, engage in coalitions and make compromises to exert influence on Syria's political life". Such present-day pragmatism is nevertheless tempered by the jamiats' devotion to Ibn Taymiyyah, a 13th-century scholar, whose teachings urged a return to Quranic sources. Repression under successive military regimes from 1949 to 1954 blunted the Brotherhood's political activities, and it pulled out of elections in 1954, the same year that President Gamal Abdel Nasser, rising as the Arab world's charismatic if despotic post-colonial hero, was imprisoning Brothers across Egypt.

Although the Syrian Brotherhood returned to electoral politics in the 1960s – as much as elections existed under the Baath Party – its members often ran as nominal independents, much like Egyptian Brothers would do under Mubarak. The Baath Party’s growing dominance of Syrian politics would lead to the Syrian Brotherhood’s fragmentation and, later, radicalisation. Its more moderate “Damascus wing” split with factions in Aleppo and Hama over political and strategic differences, and the personality of Issam Al Attar, Sibai’s successor. Al Attar was deported by the regime and went to live in the German spa town of Aachen, where Lefèvre interviewed him – one of a series of unique interviews with prominent, exiled Brothers. The schism diminished the Damascene moderates and elevated the increasingly aggressive factions centred in Hama, where a young militant, Marwan Hadid, led a brief insurrection against the government in 1964.

Like Al Sibai and Al Hamid before him, Hadid befriended a leading Egyptian Islamist in Cairo – the radical Sayyid Qutb, who promoted a vision of unyielding confrontation with secular Arab regimes that later became the ideological foundation for Al Qaeda. The details of Hadid's rebellion mirror contemporary events in Syria. After the government removed three teachers for alleged anti-Baath views, protests grew into street riots and fighting. Hadid holed up with his followers in a central mosque, which the regime bombed, forcing his surrender. Dozens died and the crackdown was, Lefèvre notes: "remembered by Hamawites and religious Syrians as an act not only of Baathist secularism but also unyielding atheism". Hadid's insurrection led, through a series of increasingly violent tit-for-tats between the regime and primarily Hadid's Fighting Vanguard, a radical branch of the Brotherhood, to Hama in 1982. Law 49, passed in 1980, made membership in the Muslim Brotherhood a capital offence. After an assassination attempt on Hafez Al Assad failed that same year, forces under his brother Rifaat – the field marshal in the Hama massacre – killed up to a thousand prisoners in Palmyra. As one of the soldiers later admitted, when their helicopter returned to the base in Mezze in Damascus, "a major welcomed us and thanked us for our efforts".

The Syrian Brotherhood was transformed by bullet and bombardment, prison and exile. While some Egyptian members and offshoots like Al Gamaa Al Islamiya were radicalised by their own experience of repression and imprisonment, the Egyptian Brotherhood changed more through elections in student unions, professional syndicates, and eventually parliament. The Brotherhood might have joined the formal political system to change it, Wickham writes, “but they ended up being changed by it themselves”.

Two years after Hama, while Syrian Brothers were in exile or regime detention, or joining the jihad in Afghanistan, the Egyptian Brotherhood under Umar al-Tilmisani, its third Supreme Guide, announced that it would start contesting elections. Anwar Sadat had opened Nasser’s jails and brought the Brotherhood back into public life. “The participation of Islamist groups in the political process not only generated new strategic interests but also prompted internal debates about their ultimate goals and purposes,” Wickham writes. Younger members, exposed to diverse viewpoints in student unions, trade groups and parliament, began to argue with the old guard over reforming its conservative views on political pluralism, women’s rights, and religious minorities and even to democratising its internal dynamics and practices. By 1996, this rift led to the breakaway, moderate Wasat Party.

Wickham eschews broad proclamations for measured analysis, at times leading to wavering conclusions. “Facile generalisations gloss over the internal complexity of Islamist groups and understate the profound tensions and contradictions that permeate their agendas,” she writes. But Morsi’s sudden fall, and the reset of Egypt’s transition back to the military as political arbiter, warrants other conclusions. Using Wickham’s description, the Brotherhood in fact succumbed to the “double dilemma” that greeted Morsi in the presidential palace: it pushed too hard with its electoral mandate, provoking a backlash from entrenched, still-powerful regime institutions, and it advanced a partisan agenda that alienated a swath of society that then mobilised against it.

The irony of these parallel accounts is that, with Egypt's current disorder and Lefèvre's analysis, which privileges the Brotherhood's early pragmatism and democratic participation over their violence in the 1970s and 1980s, the Syrian Brotherhood – long considered more radical – comes across as more of a political moderate than its Egyptian relative. Lefèvre insists that "today, there is little doubt left about the organisation's commitment to ideas and concepts such as democracy and political pluralism," even if it still remains doctrinally "embedded in the ideological substance of political Islam". Its internal history is far more contentious, and reflective of the broad social and political wounds of decades of single Baath Party rule, than is often framed. In Egypt, meanwhile, where the Brotherhood's history was never so violent, the group instead participated in what Wickham calls "a political process warped by authoritarian rule". That didn't liberalise the organisation so much as entrench hardliners who kept it as a closed coterie. Under Mubarak, the Brotherhood knew it couldn't reasonably hold power, so it was free to advocate democracy while leaving major doctrines and policies vague. But political power changed all that, and exposed their doublespeak. It ran a presidential candidate after pledging it wouldn't; it deflected criticisms with canards, and refused to admit mistakes.

Until the Syrian Brotherhood runs in elections and realises similar political aspirations, the organisation will be held up to its Egyptian counterparts and their penchant for saying one thing while pursuing only narrow group interests. The interviews Lefèvre cites give voice to his broad claims about the Syrian Brotherhood's newfound restraint and accommodations. But if the Egyptian Brotherhood has proven anything after Mubarak, and after Morsi, it is that its words are hardly sacrosanct. Exiled Syrian Brothers such as Attar or Salem, whether they want to be, will be associated with Khairat Al Shater, the Egyptian Brotherhood's senior strategist and chief financier, who told the state-run Al-Ahram newspaper last year: "There must be as much integration and cooperation as possible, with alliances and coalitions among the various political stakeholders … There is no possibility of a power monopoly. It simply is not part of our strategy or our culture."

Frederick Deknatel, a regular contributor to The Review, is a staff editor at Foreign Affairs.

thereview@thenational.ae