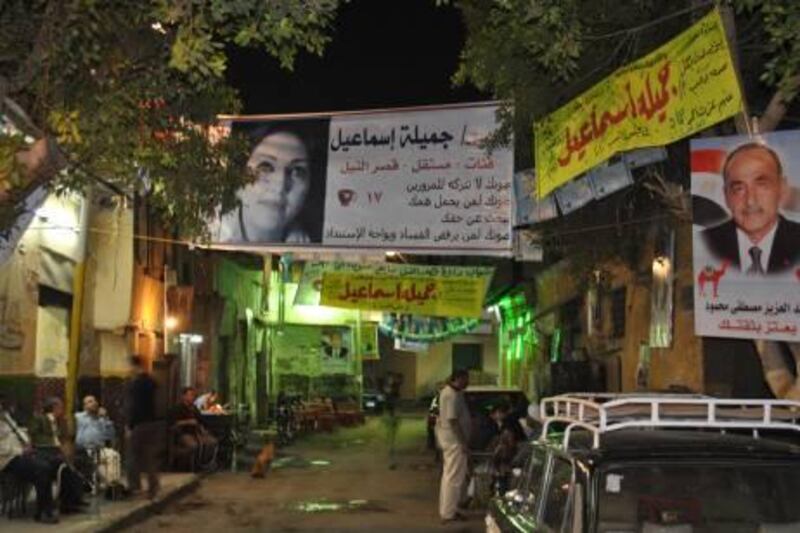

As one strolls through the downtown Cairo neighbourhood of Mosbiro on Monday, the dozens of campaign leaflets, hand-held signs and banners make Gameela Ismail's face seem everywhere - on walls, windows and jacket lapels.

The cultural repercussions are just as overwhelming. Five years ago, the image of a woman's face beaming from a campaign poster - instead of a stare from a film advert - would have been an exceedingly rare sight. In the 2005 election, only four women were elected to Egypt's 454-seat parliament, and four more were eventually appointed by Egypt's president.

The 2010 vote promises to be different. A law passed last year will expand parliament to 518 members, and guarantee seats for at least 64 women, all of whom will run against other female candidates in special polls. The law has been lauded as a strong positive step for an Arab country that is often considered a bellwether for women's rights in the wider Middle East.

So why would Gameela Ismail,an independent candidate and by far the best known of the more than 700 women running for Egypt's parliament this year, opt out of the new quota system?

"This quota was established in order to ensure more seats for the ruling party," Ms Ismail said to the clutch of reporters who were following her around Mosbiro this week. "It's not the Egyptian women who need a quota. It's all the Egyptian people who need a quota in order to have their political and social rights heard. "

It is a perspective that sounds terribly cynical - even ungrateful - considering how the social status of Egyptian women has receded substantially during the past several decades, even as their formal legal rights have improved.

Yet women themselves seem almost as unlikely as men to vote for a female candidate.

Even though the conservative Muslim Brotherhood, a technically illegal Islamist political opposition group, has fielded an impressive 15 female candidates under the quota system, Egyptian attitudes toward women still lie far afield from those in Europe or the West.

"I'm not convinced that a woman can be president, but maybe a minister of economy or education," said Doaa Reda, 23, a customer service representative for a telecommunications company, who was smoking a cigarette at a downtown Cairo cafe last week. "I'm very sensitive. There are some situations that require strength. For example, if I was giving a big political speech and a baby started crying, I would drop everything to go look after the baby."

Despite such pervasive attitudes, women in Egypt have carved out prominent places for themselves in business, law and medicine.

In 1984, Egypt's parliament could boast 36 female members under a quota regime that was later repealed - it was deemed unconstitutional - in 1988.

As women's voices have become increasingly muted in politics, protests from civil society organisations and women's rights groups have grown louder. In that light, last year's quota law looked like a major coup.

"I support [the quota] because I have proposed it for eight years and it used to be refused until the constitutional amendment initiated by the president" last year, said Georgette Qollini, a parliamentarian for the ruling National Democratic Party (NDP) and one of the four female legislators who were appointed by Egypt's president, Hosni Mubarak.

"When men compete with women in elections, the men use all the weapons that women don't feel they can use, like bullying and rumours. In addition there is an anti-women culture among the common people in the street," she said.

All of this is true, say Egyptian feminists. But it is the "type" of woman whom the new quota will support that has become a cause for concern.

Instead of running alongside male candidates in one of Egypt's 222 individual voting districts, female candidates in the quota system must run for office at the level of an entire governorate, of which there are only 29 nation-wide.

"Having a woman who is running for the whole governorate, you need a woman who is already empowered. You need either a wealthy woman or you need a woman from a prominent tribe or family," said Mozn Hassan, the chairman of the board of Nazra for Feminist Studies, an advocacy group that is monitoring the elections "from a feminist perspective".

Ms Hassan continued that "you need a woman who is supported by a strong political party because it's not only a small place, it's a whole governorate".

In the end, she said, women's rights in Egypt should be more about quality and less about quantity.

[ mbradley@thenational.ae ]