CAIRO // Egypt's new president, Mohammed Morsi, was in Addis Ababa yesterday, amid tense relations between the two countries over the Nile river.

Egypt and Sudan, which rely on the Nile river for nearly all their water needs, are in a deadlock with the other Nile Basin countries, including Ethiopia, over rights to use the water.

During the political chaos after Egypt's Hosni Mubarak was forced to resign as president last year, Ethiopia announced it was moving ahead with an enlarged version of its US$4.8 billion (Dh17.6bn) Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam - Africa's largest hydroelectricity project.

Egyptian officials believe the dam, under the specifications revealed, would drastically cut the amount of water available and cause economic and humanitarian problems in Egypt.

Ethiopia is home to the source of the Blue Nile, which flows downstream to Sudan and then farther north to Egypt. The Blue Nile contributes the majority of the river's water from the point it meets the White Nile outside Khartoum, the Sudanese capital, and all the way north to Egypt's Mediterranean coast.

The two-day visit of Mr Morsi to Ethiopia was itself a milestone. Mubarak refused to return there after he narrowly escaped an assassination attempt by Islamic extremists in Addis Ababa in 1995.

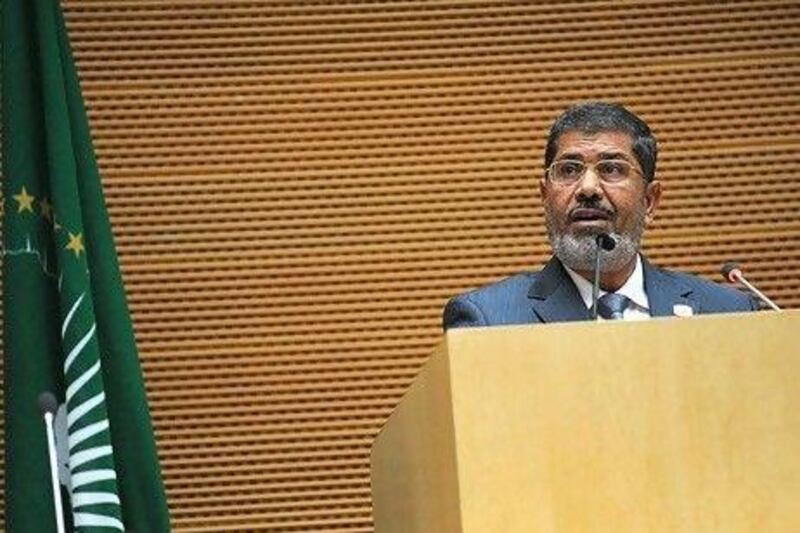

Mr Morsi began his visit yesterday with a speech at a meeting of the African Union, where he said that Egypt needed the support of African nations to "rebuild" and called for a stronger "African market".

"I would like to officially announce that Egypt has a desire to work towards a common African market," he said. "Egypt will use its human and financial resources to ensure that. We stress our concern with education, health, construction and development."

His diplomatic overtures hinted at Egypt's growing concern that Nile Basin countries were moving ahead with development projects that would cut the flow of water to Egypt and Sudan.

The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam would cause "political, economic and social instability", said Mohamed Nasr El Din Allam, who was Egypt's minister of water and irrigation from 2009 until early last year, in an interview in March. His dire forecast came after Ethiopia announced its dam would be dug to a depth of 150 metres, compared to the earlier specification of 90m, to provide more electrical power and water for irrigation projects on new farms.

Depending on the speed with which Ethiopia could flood its dam, the problems could range from bad to devastating, he said.

Ethiopia, one of the world's poorest countries, is seeking to become a power exporter with a series of dam projects over the next several years.

Disputes over water rights among the 10 countries that form the Nile Basin have been simmering for years.

Egypt receives 55 billion cubic metres and Sudan receives 18.5bn cubic metres per year, under a series of agreements that date back to a 1929 treaty drawn up by Britain when it held power over much of North Africa. But upstream countries, such as Ethiopia, have argued that those agreements, which give Egypt and Sudan veto powers over projects that could be "harmful" to their interests, were signed during the colonial era, and should be rewritten to allow countries to equally share in the river's economic potential.

A framework for discussions, the Nile Basin Initiative, was set up in 1999 to establish an equitable agreement among the countries.

However, the talks have are in limbo because of Egypt and Sudan's unwillingness to negotiate their current share of the water and insistence on keeping veto rights.

Ethiopia, Uganda, Tanzania, Rwanda and Kenya signed an alternative deal, known as the Entebbe Agreement, that said projects could be built as long as they don't "significantly" affect the water flow. Egypt called the agreement a "national security" threat.

Ethiopia in particular has become increasingly confrontational with Egypt. Prime minister Meles Zenawi said in a television interview in 2010 that "some people in Egypt have old-fashioned ideas based on the assumption that the Nile water belongs to Egypt … The circumstances have changed and changed forever".

The dispute between Egypt and Ethiopia calmed somewhat after the two sides agreed last year to create a technical committee to assess the impacts of the dam. A report is not expected until next year.

Egypt's main diplomatic tool in negotiations is its ability to lobby foreign donors and international organisations to withhold financing for the dam because of the adverse impacts on its economy. Ethiopia has issued bonds to raise money for the dam, but cannot finance it alone.

Follow

The National

on

[ @TheNationalUAE ]

& Bradley Hope on

[ @bradleyhope ]