As Major League Baseball winds up its pitch to China, envisioning a billion fans, Michael Donohue watches from the empty bleachers.

Perhaps the most interesting moment in the history of the China Baseball League occurred one evening last year in the city of Wuxi, about 80 miles west of Shanghai. It was late May, and the league's All-Stars had gathered for a mid-season showdown between the North and South divisions. The red flag with its five golden stars waved gently next to the scoreboard. Freshly chalked baselines glowed against the clay and grass. Construction-site dust blew in over the right field wall.

On the mound, pitching for the South despite being only 19 years old, stood Liu Kai, left-handed ace of the Guangdong Leopards and probably the most talked-about prospect in Chinese baseball. You might not have guessed this from looking at him. Liu had the guileless face of a middle-schooler. Though just over six feet, he had soft arms and little legs that made his pants droop. On the mound, however, he had a fluid delivery and - by Chinese standards - a treacherous curveball. A week before tonight's game, he'd thrown a shutout against the Shanghai Eagles, striking out sixteen batters. And though his fastball, by American standards, wasn't actually very fast, he was about to sign a minor-league contract with the New York Yankees.

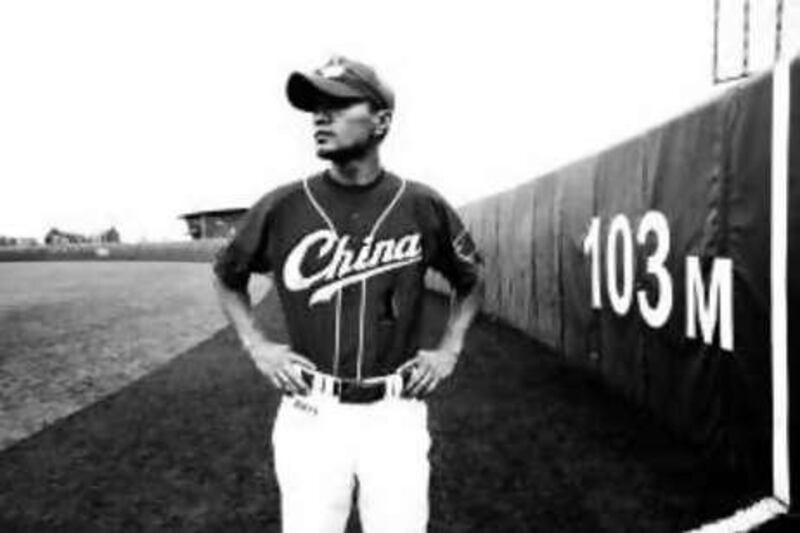

After two quick outs in the first, the North sent to the plate a lanky centre fielder with a seemingly permanent goofy look on his face. By some measures, Wang Chao was washed up. Back in 2001, when he was just 16, he had signed with the Seattle Mariners, who liked his height - six-foot-four - and thought they might turn him into a pitcher. He got a $30,000 signing bonus, and had the honour of being the first mainland Chinese player to join a major league organisation. Then he spent two fruitless years in the lowest level of the minor leagues, failing to rise in the so-called farm system that cultivates players for the majors. He acquired a reputation for not working very hard. "He just didn't want to do the things he needed to do to be successful," Ted Heid, Seattle's head scout for Asia, told me. So Wang went back to China, his big chance blown. Tonight he didn't look too upset about it. Now 22, he wore a cocky smile and seemed to be constantly looking around for someone to share a private joke with.

For the first time in the CBL's six seasons, two players good enough to sign Major League Baseball contracts were facing off. Wang the ex-prospect, the failed pioneer, stood in the batter's box before Liu, the league's new golden boy, the future Yankee farmhand and maybe, some said, the player destined to lead the way for generations of Chinese big leaguers. Here was the glorious future of Chinese baseball pitted against its fallen past, the self-effacing kid against the facetious lollygagger.

Not that anybody cared. On this warm, clear night in a city of four million, no more than 175 spectators were on hand for the first inning (in a stadium that could hold 3,000), and far fewer were actually paying attention. Almost all were students from the nearby Wuxi University of Science and Technology, and they had come to the game for one reason only: they had been ordered to.

"That's just the way it works here," explained Zheng Cong, one of the country's few authentic baseball fans, who tallies statistics for the CBL's website (and who carried a Mandarin translation of the bullpen guru Tom House's Fit to Pitch). In a country where almost everything has some connection to government, a sports official can phone up a university administrator and simply place an order for a few hundred bodies. The crowd would eventually swell to about 600, and photographs of the game - the ones seen by the league's main sponsors, Mizuno and Canon - would make it look decently attended. But most of the coerced fans weren't even pretending to watch, and during Wang's at-bat against Liu the stadium had the melancholy air of a school assembly. When Liu, after falling behind in the count 2-0, inveigled Wang into swinging at a slow, seemingly listless but deviously unhittable breaking ball, and then did the same thing again, and then again - and when Wang, having struck out, headed back to the dugout for his glove, laughing off the at-bat as if it had all been just a lark, the only spectators who paid much attention were sitting in my row. A few innings later, league staff passed out thunder sticks, and for a while the students banged them together happily, making a sound like hail falling on a tin roof. Then they lost interest. By the sixth inning, most of the crowd was gone. The few who remained caught a late-inning promotion in which everyone in the stands released an inflated balloon at the same time. In the ninth, the North staged a dramatic rally and came from behind to win the game, 4-3. Somewhere in a forest, a tree fell.

Does baseball exist in China? Most Chinese will tell you no. In fact, they'll give you a gentle, pitying look just for asking the question. Technically, they're wrong. But there are only 20 baseball fields in the entire country, according to Shen Wei, the secretary general of the China Baseball Association, a tiny department within the state sports ministry. About 400 Chinese make a living playing baseball, affiliated with the state sports system. Another several thousand play on loosely organised school and university clubs, usually setting up their bases on soccer fields. Exact figures are a state secret, but it's possible that the number of people executed annually in China only recently dropped below the number of people who play organised baseball. Still, in recent years American baseball evangelists have come into China full of big hopes to make a few million converts. They want to turn the sport from an obscure underground into a popular pastime - and maybe, in the process, sell a billion hats and shirts. "We would be foolish not to pursue it," says Bob DuPuy, chief operating officer of Major League Baseball, an organisation whose revenue last year topped $6 billion, including a reported $70 million from Japan. In 2003, MLB hired Jim Lefebvre, the former Los Angeles Dodgers infielder and veteran manager, to coach China's national team. Assisted at various times by former big-league players like Bruce Hurst, Steve Ontiveros and Barry Larkin, Lefebvre's mission was to prepare the team for the Beijing Olympics, where MLB hoped a strong showing might push baseball into the Chinese spotlight. The league arranged for six Chinese players to have reconstructive surgery on their throwing elbows, and has frequently flown Lefebvre's squad to Arizona for training. The ultimate goal, naturally, was not merely to improve China's national team, but to find one player good enough to play in the big leagues - a "Yao Ming of baseball" who, it was believed, could do for the game what the Houston Rockets centre had done for NBA basketball. The first Major League team to field a mainland Chinese star just might suddenly have its games broadcast on CCTV and see its merchandise become hot property among the 300 million Chinese between the ages of 15 and 30. By 2007, Major League Baseball was ready to "go all in" with its China plan, said Jim Small, the league's vice president for Asia. It sent a young Mandarin-speaking Texan, Mike Marone, to start a Beijing office, and hired Rick Dell, who had coached at Rutgers since 1982, to operate baseball camps for Chinese youth. Thirty MLB merchandise shops opened in 15 different Chinese cities. The Dodgers and the San Diego Padres prepared to play two spring-training games at the newly constructed Olympic ballpark in Beijing. The Yankees signed their own agreement with China's sports ministry, and set up their own youth camp. Even the US State Department got involved, flying 12 Chinese coaches to America to train with the legendary retired shortstop Cal Ripken, then sending Ripken to Beijing and Shanghai as a special envoy. And for the first time since the failed Wang Chao experiment six years earlier, in June of last year two MLB teams signed Chinese players to minor-league contracts. Baseball's big push into China had begun.

Tom McCarthy is a man of big ideas. A few years ago, when he was running the China Baseball League, he advised on the design of the future Olympic stadium. "I wanted to put a replica of the Green Monster out in left field," he told me, referring to the famously high-topped wall at Fenway Park in his native Boston. "But on it you'd put, 'THE GREAT WALL.' Then you'd have the Temple of Heaven in centre field, OK? And the columns outside the stadium?" He paused for effect. "The terra cotta warriors." (The construction company took a simpler approach.) A tall, fast-talking man of 58, McCarthy first moved to China in 1987 to supervise factory production for a shoe company. Soon, though, he found a better calling: persuading Chinese people to play basketball. Over the last two decades McCarthy has run coaching clinics, done commentary on TV broadcasts, brought retired NBA stars on sold-out Chinese tours, served as CEO of the Asian Basketball Federation, and even done some scouting for the Orlando Magic. In 2001, an official from the China Baseball Association approached him with the idea of switching sports. "I thought, 'I got to roll the dice here,'" he recalled one morning in his office near the Temple of Heaven. China's selection as an Olympic host meant that its baseball team would qualify for the first time, and the government was known for pouring resources into the quest for medals. It seemed to McCarthy that the game's time had come. "Any time China decides they want to be good at a sport," he explained, "and the big elephant picks up its little foot, they crush the other countries." In one way, the China Baseball League was easy to assemble: the teams already existed. Despite an oft-printed myth holding that Mao Zedong banned baseball as a "bourgeois game", three of the existing teams - Tianjin, Shanghai and Beijing - had got started in the years just before Mao's death in 1976. But these ballplayers, in keeping with the factory-like nature of the Chinese sports system, practiced a lot without playing many actual games, and teams had never considered trying to draw many spectators. McCarthy thought that with heavy marketing, he could attract crowds to the games and sell lucrative corporate sponsorships. He picked the best four teams, clothed the players in snazzy new uniforms, and opened the first CBL season in 2002. Tommy Lasorda, the former manager of the Los Angeles Dodgers - who, incidentally, got punched out by Jim Lefebvre at an LA radio station in 1980 - threw out the ceremonial first pitch before the league's innaugural championship. McCarthy and his company marketed the venture aggressively and got fairly wide coverage in Chinese media. "We committed our heart and soul 24 hours a day to baseball in China," he says. By the 2004 season, each team had a 36-game schedule - nowhere near the 162 games played by MLB teams, but fairly impressive for a brand-new league in a country where bureaucrats actively campaign against athletes' playing too often. The next year two expansion teams joined the league. But the crowds didn't come. Neither did sufficient sponsors. Early in 2006, McCarthy realised that the investment - the commercial rights alone cost 8 million yuan (Dh4.3 m) a year - was never going to pay off. He says he offered MLB a stake, which they turned down (MLB denies the offer was ever made). Shortly before the start of the 2006 season, McCarthy gave up on baseball in China. Softbank, the Japanese corporation, bought out McCarthy's rights, then promptly let the CBL sink into even deeper obscurity. And the man from Boston moved on - to Chinese tennis.

"No, I've never seen baseball," said Pi Hongjie, "but I don't think I'll like it." Pi, a native Beijinger in his mid forties, was driving me in his taxi down to Lucheng, a remote area 20 kilometers southwest of Tiananmen Square, where the Beijing Tigers were playing in the 2007 CBL playoffs. Like almost everyone else in Beijing, Pi didn't know the team existed. I'd been to every Tigers home game that season - not many, since the regular season in the post-McCarthy era goes a paltry 21 games - without meeting anyone else who would qualify as a fan. Attendance was usually in the mid to high two figures, with most spectators being either relatives of the players or else students from the Lucheng Sports School, who were - of course - required to show up. The Tigers' dramatis personae included a dexterous, big-bellied third baseman, a rookie right fielder with a mullet, and a pitcher with a disturbing facial resemblance to Mohammed Atta (who somehow humiliated batters with his sluggish 69-mph fastball). My favourite was clearly Sun Lingfeng, a centre fielder with the truncated body of a jockey. Never has a man with such short legs run so fast, and never before has a person who earns his living playing the outfield possessed a throwing arm worse than mine. He compensates in other ways. Whoever first called him "the Chinese Ichiro" must have based the label on Sun's knack for somehow getting on base no matter where he hits the ball, and on the fact that he can steal second base at will against CBL catchers. Alone among the Beijing players, Sun had an attitude: he glowered after losses, occasionally threw his helmet, and wore a huge tattoo of a wolf on his shoulder. The rest of the Tigers seemed amazingly innocent. Like most Chinese athletes, they came up through the state sports school system, where from the age of 13 they had little contact with non-athletes. Even the veterans had boyish demeanors, and even the best players seemed incapable of boasting. They sleep three to a room in dormitories, eat all their meals together, and assemble each morning for 7.15 roll call. "I have to take care of everything," Li Bing, the team's manager, told me. "When they should go to bed, their laundry, what they eat." Li, a former national-team player, is tall, 50, and still athletic. He broods, wears dark sunglasses, and smokes between innings. One afternoon in 1974, Li told me, he was walking through a park in central Beijing and saw a group of men playing a strange game. He thought it looked like something he'd played as a little kid in his hutong, in which one boy would hit a leather ball with his hand, and another would run between two, or sometimes three, electricity poles. "I had never seen people batting a ball and running through a square," he said. The next year, when he was 16 and a stand-out athlete at his school, Li Bing became one of the first members of the Beijing Tigers. Baseball has been his life ever since. In the 1970s and Eighties, when almost every Chinese person lived in a danwei, or work unit, life as a professional athlete - with its communal living and miniscule pay - was not much different from that of a factory worker. These days, while the rest of the country has largely dropped the work-unit system and rushes headlong into capitalism, athletes are still living danwei-style. The Tigers earn between 1,000 and 2,000 yuan - about Dh535 to Dh1075 - a month. Married layers live apart from their wives. What Li Bing says of his own playing career still applies: "No matter how many championships I won, I knew my life would stay the same." Two Tigers do have a chance to break out of the system. Last year, the Mariners gave minor-league deals to the chipper slugger Jia Yubing, nicknamed "Pipi", who led the team in home runs - with four - and to the veteran catcher Wang Wei, who hit the first home run of the World Baseball Classic in 2006. "I've been telling people about Wang Wei for years," John Gilmore, a scout for the Cincinnati Reds, told me last year. "He had a glove-to-glove time" - the time it takes a catcher to throw down to second base - "of 1.8 seconds, which is better than the average major league catcher. But most teams haven't paid much attention to China." And now, the scout added, Wang is too old be considered a serious prospect. He will turn 30 on Christmas Day.

"I'm not saying 'the baseball Yao Ming' anymore," said Mike Marone, manager of MLB's Beijing office, one October afternoon last year, as we stood in the cold watching Cal Ripken cavort with 10-year-olds. "I'm just not saying it." It's understandable why a man might tire of the phrase: you hear it from almost every English-speaking coach, scout, executive, promoter and hanger-on in Chinese baseball. There's a flaw in the Yao-of-baseball theory. China's embrace of the NBA actually happened long before the Rockets drafted Yao in 2002. By the mid-1990s, Chinese state television was airing three NBA games a week. It seems the country was enamored of a certain Chicago Bulls guard named Qiao Dan, known in some parts as Michael Jordan. Working out of two small rooms on the 15th floor of a Beijing high-rise - their walls decorated sparsely with a few baseball posters - Marone and Rick Dell aren't primarily charged with finding a Yao. Instead, they're focused on spreading baseball at the grass-roots level, by exposing as many children to it as they can (MLB's Play Ball program, which gives a basic introduction to the game, has visited 120 elementary schools), by trying to get baseball on television and by connecting middle- and high-school players with experienced coaches. Though the pool is small, American scouts have noted that there's some real talent in it. "I saw the best 12-year-old I've ever seen," Tim Kessner, a scout for the Philadelphia Phillies, said of an MLB youth camp he attended last year in Wuxi. When four Chinese players signed MLB contracts last year, some said it marked the beginning of a long parade of Chinese prospects. "We look at China as being the greatest open market for future players," Ted Heid told reporters at the Mariners' signing ceremony in Beijing. But these four - the two Beijing players recruited to the Mariners; lefty Liu Kai and Tianjin catcher Zhang Zhenwang to the Yankees - are not likely to become the Yaos of baseball. A month before these players signed, I spoke to Jim Lefebvre on the telephone. Not knowing yet about the Yankees' deal with Liu Kai, Lefebvre said the young pitcher has "definitely got a live arm and you would call him one of the best prospects out there" for China. But when I asked him whether a team might bring Liu into its minor-league system, the manager was direct. "Listen," he said, "there's a huge, huge interest in China right now, but there's nobody that can take anybody's job. Why would you take a [minor league] spot and replace it with somebody who's got no future on your team?" Six weeks later Liu Kai was at Yankee Stadium, standing next to Zhang Zhenwang and facing the New York media. Lefebvre, reached again on the phone, said the signings were "tremendous" and "a great step forward."

Three years ago the International Olympic Committee voted in a closed session to eliminate baseball from future Games, starting in 2012. (There's a small chance it might be re-instated for 2016.) Thus it happened that the men of the China national baseball team found themselves, this past August, playing a soon-to-be-scrapped sport in a soon-to-be-razed stadium.

Early in the afternoon of August 15, a week after the opening ceremonies, things weren't looking too good for Lefebvre's team. They had never fared well in international play. In the 2006 World Baseball Classic they'd been outscored 40-6, losing all three games. Two days ago, in their Olympic debut, they'd gotten drubbed by Canada, 10-0, in a game shortened by the "mercy rule". Today they were playing Taiwan, and they especially wanted to avoid embarrassment against a country that China considers its own rogue territory. Baseball is big in Taiwan, which dominated the Little League World Series all through the 1970s and Eighties and has sent several players to the majors, including one of the Yankees' top starting pitchers, Wang Chien-Ming.

The underdogs had played better than expected today and sent the game to extra innings. But now, in the top of the 12th inning, Taiwan's much more muscular hitters had blown the game open on a string of walks and hits, and now China was losing 7-3. The many Taiwanese fans in the stands were singing, "Na na, na na na na, hey hey hey, good bye."

What happened next was one of the strangest occurrences of the Beijing Olympics. In the bottom of the inning, losing by four runs, China loaded the bases with no outs. Second baseman Li Lei struck out, but Wang Chao, the old ex-prospect for Seattle, drove a single into left-centre, cutting Taiwan's lead to 7-4. The next batter flied out. Sun Lingfeng (my favorite Beijing player) walked, driving in another run. Now, with China down 7-5, the switch-hitting designated hitter, Hou Fenglian, came up with the bases loaded and two outs.

Batting left-handed against the right-handed pitcher Yang Chien-Fu, Hou took a fastball for a strike, then couldn't check himself from swinging at a curveball in the dirt. Taiwan needed only one more strike to win the game; Yang threw the ball in near the batter's hands, hoping to jam him, but Hou got around on it and hit a ground ball into right field.

This was bad news for Taiwan, but it did not seem, at first, disastrous. A single like that should have driven in two runs, leaving the game tied. Scoring from first base on a single is one of the rarest events in baseball. But it wasn't just any player who had started running from first. It was Sun Lingfeng, the speed demon with the wolf tattoo, and suddenly - so suddenly that the TV cameras didn't even capture it - the "Chinese Ichiro" was storming toward the plate, the ball was dribbling away from the second baseman and the Chinese had beaten Taiwan, 8-7.

Tomorrow, reports in the media would be scanty. The players would not become famous. Office workers would not argue about calls to the bullpen. Radio hosts would not re-hash key moments with callers from the suburbs. Lefebvre's team would lose the rest of their games. Baseball still didn't matter in China. But today, looking at the swarm of white jerseys jumping jubilantly around home plate, you never would have known it.

Michael Donohue lives in Beijing. He has written for The Review on the sinophile Sidney Shapiro and on the world's largest mall.