A woman in a red dress recoils from a tear-gas assault by a Turkish riot policeman. Another young woman gasps out her last breath on a Tehran street. A student brings a column of Chinese tanks to a halt with nothing more than two supermarket bags.

In historic events involving tens of thousands, often hundreds of thousands, sometimes a single image of a single person can capture the spirit of the moment.

So it is with the mass demonstrations this week in Istanbul's Taksim Square.

Captured by a Reuters photographer, Osam Orsal, the defiance of the mostly young and secular protesters was epitomised by, in the initial absence of her name, the Woman in Red.

In the past few days her image has been reproduced not just in publications and on news websites, but on posters, stickers and walls across Istanbul.

In a simple but elegant outfit more suitable for a garden party than a riot, the woman, identified as Ceyda Sungur, an academic at Istanbul Technical University, has become a symbol of the innocence and naivety of the city's young in confronting the brutal machinery of authority.

Such images linger in the public consciousness long after the events they evoke have passed into history.

Perhaps the most famous of all occurred in June 1989, near Beijing's Tiananmen Square. A column of tanks sent in by the government to crush mass demonstrations was halted by a lone man, who blocked their path.

Out of the estimated one million people who gathered in the square, this one man came to symbolise their cause. Known to this day only as Tank Man, his identity and fate have been fiercely debated but never resolved.

Anonymity, and with it the ambiguity of motive, can sometimes play an important factor in the iconography of these photographs.

One of the earliest came in 1967 as demonstrators marched on Washington to protest against the Vietnam War. Facing the ranks of national guardsmen, a young man in a baggy sweater placed a carnation down the barrel of one of their guns.

The moment was captured by Bernie Boston, a photographer for the Washington Star newspaper. And while the protester has never been firmly identified, his action helped to define a movement still remembered as Flower Power.

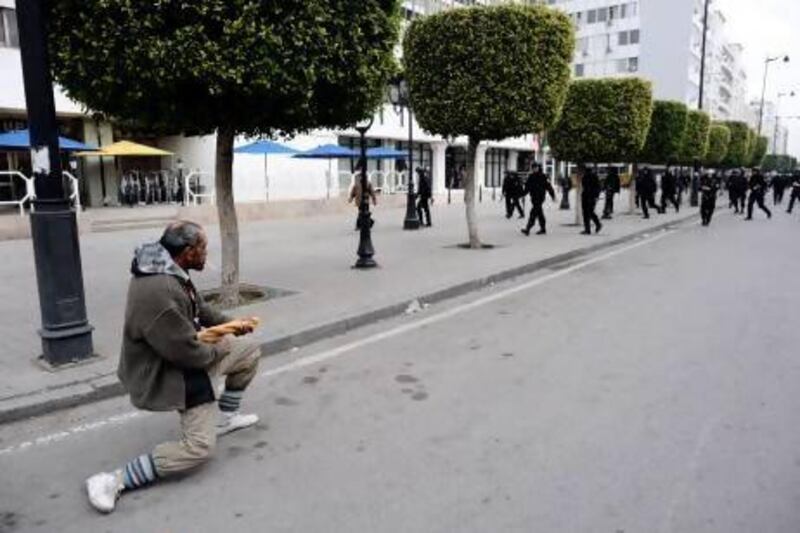

More recently, the 2011 Tunisian protests that ended the rule of the president, Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, were in part symbolised by the appearance of "Captain Khobza", a middle-aged man who turned to confront the approaching ranks of riot police holding a baguette as if it were a machine gun.

The symbolism of the bread - introduced under the colonialist era of France but frequently in short supply under the regime of Ben Ali - was not lost in the Arab world.

Sometimes, though, the story is as significant as the image. Neda Algha-Soltan was heading for a demonstration against the results of the 2009 Iranian election when she was cut down by gunfire from a militiaman loyal to the president, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

Several videos captured the moment, but a single frame came to represent her death and the crushing of the Iranian opposition movement. The 26-year-old former student lies on her back, eyes wide with fear and pain, as others try hopelessly to stem the bleeding.

According to some, her last words were, "I'm burning, I'm burning." Time magazine called it "probably the most widely witnessed death in human history".

In the final weeks of the regime of Libya's Col Muammar Qaddafi, it was Iman Al Obeidi, a woman in her mid-20s, who confronted the international press corps at a Tripoli hotel with her allegations of rape and beatings by government forces.

Her bloodied appearance and clear distress, and the attempt by government security forces to abduct her under the noses and cameras of the world's media, gave the opposition to Qaddafi's repression a human face. Al Obeidi was later given asylum in the US.

As with Algha-Soltan, Al Obeidi's ordeal was captured not in the single frame, but on a digital stream that was almost instantly uploaded to the internet.

In contrast, Boston's flower power image of 46 years ago was ignored at the time, placed on an inside page of the paper. It only acquired its power months after the demonstration was over, when he won a photo contest with it.

Compare this with the woman in red. In a matter of hours, she became the face of Taksim Square.

Iconography in the digital age is almost instantaneous.