BANDA DISTRICT, INDIA // A few years ago, in the bandit-ridden badlands of Uttar Pradesh, in India's northern Hindi "cow belt", local officials decided to build a pond.

It seemed like a smart idea.

This region of Bundelkhand is one of the most wretchedly undeveloped and drought-prone in the entire country.

The pond meant several weeks' paid work for the locals and the promise of water for crops and livestock.

Unfortunately, no one in the administration had bothered to check if the ground could actually hold any water.

It couldn't.

Nor did any water bubble up from the well dug in the centre of the pond.

They built another pond a few minutes down the road.

That didn't hold any water, either.

Today, they are just two large holes in the ground, absurd and tragic memorials to the lack of care and interest that officials give to some of India's poorest and most desperate.

"It's useless," said Daya Ram, a 42-year-old farmer staring through the locked fence that now guards one of the empty ponds.

"They should just fill it up again."

Bundelkhand - which hopes to become a separate state soon - is a major battleground in the state elections being held this month in phases across Uttar Pradesh. It is India's heartland state, it most populous, with more people than the UK, France and Germany combined.

Besides the empty ponds, there are more government failures to be found a few minutes further down the bumpy dirt-track, in the village of Chandpura.

Here, they have a crumbling homoeopathic hospital, built 20 years ago.

Its only occupants are a couple of emaciated bulls. Villagers say no doctor has ever visited.

In another village, Sahabhajpur, a fancy new toilet block - whose drainage system stopped working after a couple of months - is now used to store fodder for animals.

A range of parties in this month's state elections are trying to undo the grip held by Mayawati, the "Dalit Queen" and chief minister who promised to improve the lot of India's lowest caste and won a landslide here at the last election.

Most of the 10 million residents of Bundelkhand are farmers from the bottom of India's rigid social hierarchy. Bullock carts still ply narrow dirt-tracks between villages without electricity.

Until last year's monsoon, the rains had failed for eight consecutive years. Dozens, perhaps hundreds, of people died from hunger and disease. Many more committed suicide, triggered by crippling bank loans taken in desperation to put food on the table with little hope of repayment.

In India, one of the most common forms of suicide is drinking poison such as pesticide.

"People died of starvation - even the animals would drop dead in the road," said Prema Devi, a 40-year-old community leader, describing the long years without rain in Chandpura village. They mostly ate roti, she said - the flat, unleavened bread made from the small amount of barley they could grow - along with dribblings of milk they were able to squeeze from their cows.

Five years of inaction from the government has left many deeply disillusioned with politicians.

In Banda district, banners supplied by a local NGO, the Vidyadham Samiti, have been put up at the entrance to villages, warning candidates: "Don't bother entering here unless you can tell us what you have done to help us in the past and what you can really do in the future."

Most candidates have simply stopped coming, despite efforts by the police to tear down some of the banners.

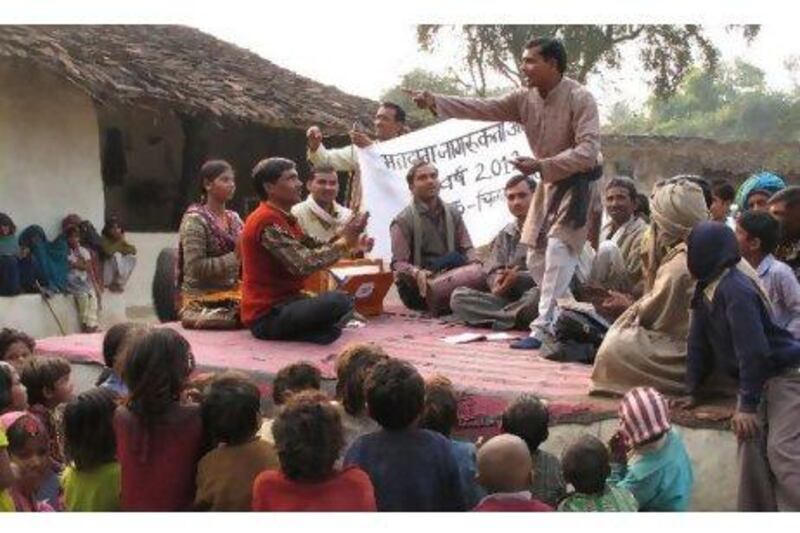

If there is any hope in a place like Banda district, it comes from people like Raja Bhaiya, who leads the Vidyadham Samiti. As well as setting up literacy classes, he organises volunteer theatre groups who travel from village to village, educating people through songs and plays about welfare schemes and how to use democracy to improve their lives.

In the village of Narsingpur last week, the volunteers were performing a play about the importance of voting.

The whole community turns out to watch. The children squeal with delight as a magician beats an arrogant and useless politician with a stick and makes him disappear.

The real magic, the magician says, is the villagers' power to vote and choose a decent candidate.

The one achievement Mayawati can claim is that she took action against the bandits, or "dacoits", who until recently ran rampant in these parts, extorting protection money and kidnapping anyone with a half-decent salary for ransom.

Many of the leading dacoits have been arrested or killed, and locals say it is much safer to travel the roads at night.

But this achievement was fatally undermined in Banda when the local legislative member from Mayawati's party was himself arrested for raping a Dalit girl.

In any case, without development, the reduction in crime means little.

An enormous $1.4 billion (Dh5.1bn), 10-year development package was introduced in 2009 by the central government.

But a report by the charity ActionAid found barely 40 per cent of the funds so far released had been used by the local administration, and that the effects on the ground were negligible.

"Mayawati is reluctant to spend any of the money because she knows the central government will take the credit," said Debabrat Patra, ActionAid's regional manager in Lucknow, the state capital.

Raja Bhaiya says people are increasingly looking beyond caste for politicians with good character who can deliver results.

"In the past, criminals would give people money and alcohol to get into power. This is what we are trying to stop," he said.

But are there any candidates of good character this year?

"Well, that's the only sad part ..."

erandolph@thenational.ae