MAIDUGURI, NIGERIA // In this relic of a medieval African empire, streets that were once lively markets for silk and perfumes now trade gunfire between Islamist insurgents and the Nigerian military.

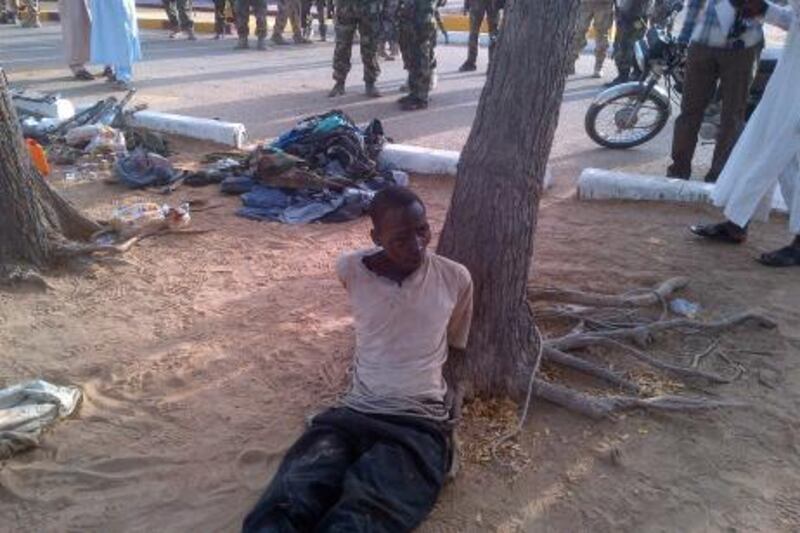

Army checkpoints at intervals of 300 metres choke the roads through parts of Maiduguri, capital of north-east Nigeria's Borno state and the centre of Boko Haram's fight for Islamic rule.

Residents of Borno, for centuries the seat of one of West Africa's oldest Islamic empires, then called Bornu, feel trapped in the middle, targets for both sides in a more than three-year-old conflict they fear only a negotiated settlement can end.

Along the bullet-pocked slums of Gwange and Kofa Biyu, on Maiduguri's outskirts, bearded members of Boko Haram hide among civilians in rubble-strewn streets that are largely deserted, save a few young children playing on sandy pavements.

Grandfather Muazu Kalari said most of the adult males in his family - the ones most at risk of being killed by one side or the other - had fled since the Islamists moved in.

"My three sons abandoned their children and wives, and so I'm left to fend for my grandchildren," he said as he arranged tomatoes on a table for sale on the empty street.

The unrest has its origins in 2009, when a cleric called Mohammed Yusuf led an uprising against the government, triggering a security campaign in which 800 people died, including Yusuf, who was in police custody.

Far from crushing Boko Haram, it triggered an angry backlash, transforming a clerical movement opposed to Western education into a violent jihadist sect that has since forged ties with Al Qaeda-linked groups in the Sahara.

Thousands have died in a conflict that has destabilised Africa's top energy producing nation. The Islamists, who frequently target the security forces, Christian worshippers or politicians, have shown no sign of giving up and no interest in an amnesty offer floated by President Goodluck Jonathan last month.

In Maiduguri, people say a political settlement may be the only hope.

"No one believes that the military with all their big guns can stop Boko Haram attacks," said Islamic cleric Maha Lawali. "They need to arrange a peace deal with these people."

An army raid two weeks ago killed dozens of people in the market town of Baga, to the north on Lake Chad, prompting calls for an investigation.

On Tuesday, about 200 suspected members of Boko Haram armed with machineguns laid siege on the town of Bama to the north, freeing more than 100 prison inmates and leaving 55 people dead, the military said.

Western powers, fearing that Nigerian jihadists are tilting more towards targeting their interests, have urged Nigeria to discipline its troops and address the underlying causes of the insurgency, which stem from the north's economic decline.

Last year Boko Haram said it wanted to revive an old Islamic caliphate, tapping into yearning for the days when Muslim sultanates thrived on trade crossing the Sahara to the Mediterranean.

Bornu was the oldest such empire in Nigeria, founded in the ninth century along the swamps around Lake Chad, and Islamicised two centuries later by Arabic-speaking gold and ivory traders plying caravan routes to Tripoli and the Nile Valley.

When Britain established a military outpost in Maiduguri in 1907, the Sultan of Bornu moved his palace there. In 1960, at independence, Borno's markets for textiles and fish from the lake prospered, but as southern oilfields began to dominate Nigeria's economy from the 1960s the north went into decline.

Now, even in the safer parts of Maiduguri where shops bustle and taxi horns hoot, everything dies after curfew at 6pm.

Chinese companies rebuilding roads have paused or pulled out, after Chinese construction workers were killed by gunmen earlier this year. Most flights to the city have come off schedule.

"These days, all I do is sweat in a shop for nothing," said Tukur Modu, sitting in a store trying to sell cloth without customers.

A climate of fear is palpable.

"You pray in the mosque and for all you know there might be a Boko Haram member praying right next to you," said Danladi Gana, whose small shop sells locally made leather goods.

"You don't know what you might say and they will mark your face, come back later and kill you - alone if you're lucky or with the whole of your family if you're not."

Fear of security forces is just as strong. Late last year Sabiyu Mohammed saw a roadside bomb hit a patrol. The soldiers started shooting randomly at people in the area, killing many, he said.

Borno state military spokesman Sagir Musa said there was no evidence that Nigerian forces targeted civilians, but he admitted that some are killed in crossfire. That doesn't reassure residents.

"The innocent people are the ones suffering from this face off between Boko Haram and the military," Lawali said, stepping up from his prayer mat. "We're caught in the middle."