The boatmen cast off from the tiny jetty with raucous shouts and hearty guffaws. As the waves caressed the wooden hull and gunwales of our small skiff, they hoisted the sails and swung the boom over ducked heads. Then our gaze turned west to the dark, sinister outline of our destination.

The straight, muscular walls of Janjira Fort rise from the sea with crenellations and bastions intact, as though still ready for battle or siege. We tacked almost parallel to it, then turned sharply and made straight for the fortress. Drawing closer, its true size became apparent - at around nine to 12 metres high, Janjira's charcoal-grey walls dwarfed our dhow-like boat. We sailed in gently towards the arched gateway and a slender stone ledge that served as a landing stage. Together with half a dozen Indian families, we gingerly stepped ashore and strolled through the large, dim gateway to explore.

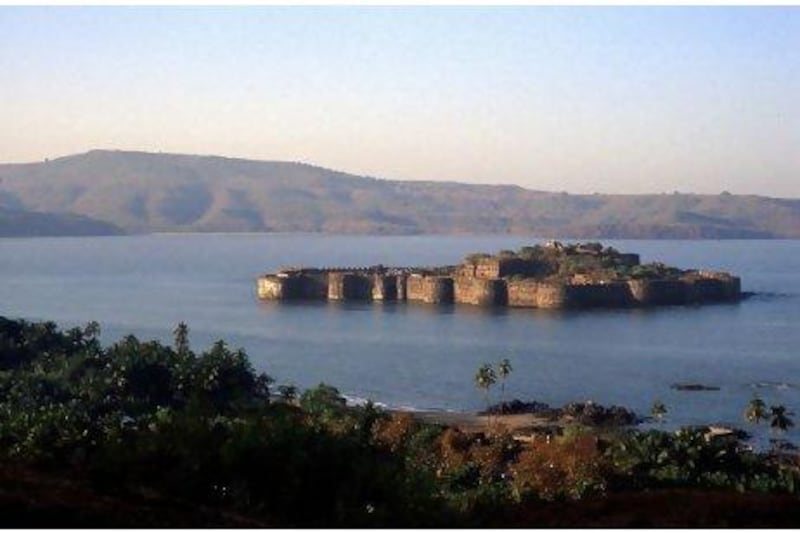

In a country blessed with some of the world's largest and most impressive forts - mostly in the desert state of Rajasthan - it should come as little surprise that India's coast was not entirely ignored. Janjira, often known as Murud-Janjira or simply Murud, is the most remarkable of the so-called marine forts that dot the Konkan coast between Mumbai and Goa. Most were built beside the sea atop hills or overlooking strategic bays. Located near the mouth of a broad creek, Janjira is an island fortress with almost a kilometre of perimeter walls rising sheer from the Arabian Sea. From afar it faintly resembles a curious and cumbersome battleship.

Its striking appearance is matched by a surprising history rooted in the so-called Siddis - mainly slaves, merchants and adventurers from East Africa who reached the Indian subcontinent from the 12th century onwards. Their reputation for bravery and loyalty made them much in demand as mercenaries for local rulers. Some went on to establish little principalities - the celebrated Malik Ambar, one-time Abyssinian (or Ethiopian) slave-turned-prime-minister, even formed his own private army and founded the city now called Aurangabad.

By the 1490s, the Abyssinian family that eventually created the small princely state of Janjira had already possessed the island. The current fort, which replaced an earlier wooden structure built by local fishermen, was begun in the early 1500s and continually expanded until the 1720s by a succession of Siddi overlords and rulers.

As we mounted steps that led up through its thick, lead-sealed walls, Salim, our local guide, pointed back above our heads. There by the main gateway was a coat-of-arms style carving of a lion dominating six elephants. "Lion of Abyssinia," he announced without explanation, meaning the Lion of Judah. Here, this ancient symbol is taken to represent medieval Abyssinian might and the Siddis' numerous victories around the Konkan coast.

We emerged near the foot of brooding skeletal ruins festooned with shrubbery. Our guide indicated scattered and forlorn tombs of some of Janjira's previous rulers and their relatives before urging us forward to the foot of Surul Khan's palace, once the fort's tallest structure but now just an imposing shell. We circled a large round masonry-lined well, now brilliant green with algae (which some guides fancifully call a lake) and headed up a flight of steps leading to the citadel. Its fabric is long gone, but from this lofty vantage point you can see Janjira's entirety - crumbling halls and pavilions, its wide walls with 18 rounded bastions and a vast stretch of Konkan coastline.

Janjira and its Siddis represent a relatively little-known but colourful footnote in Indian history. In addition to being mercenaries, they seem to have prospered from piracy and from the transport of Muslim Haj pilgrims from India's Deccan to Mecca via the Horn of Africa. The Siddis tended to side with the Mughals in their long conflict with the Marathas. It was an ultimately doomed allegiance, so by the 1730s Janjira's pragmatic wazirs cosied up to the British East India Company. Elevated to hereditary nawabs and backed by a complex genealogy, they eventually gained an official 15-gun salute.

Descending from the citadel, we made for the massive walls and spent the best part of an hour strolling from bastion to bastion along level ramparts that once bristled with patrolling soldiers and guards. Numerous old cannons, some of them huge and still rust-free, remain scattered here and there. On the western side stands a small doorway that locals call an emergency exit. Some claim the existence of "secret", and now blocked, tunnels to the mainland.

Yet to go by local lore, this was one fort that never needed such an exit. Janjira, it seems, was never successfully taken even by the Dutch and British navies, although there are numerous tales of how it was attempted. The Maratha hero Shivaji (Mumbai's airport and its most famous Gothic-style railway station now bear his name) reputedly tried several times - some sources say 13 - without success. His son inherited that obsession and commenced an ambitious undersea tunnel from the shore. When that failed, he began constructing Padmadurg, his own considerably smaller island fortress that you can still discern a little farther out at sea to the north-west.

"Janjira," continued our guide, "was invisible" - I'm sure he meant invincible - and yet more stories explain its invincibility. Having duped local fishermen in acquiring the island, those wily Siddis then tricked a local astrologer's daughter into revealing the most auspicious (think invincible) date to begin its construction. The rest, as they say, was victory. The fort and its palaces remained inhabited until the 1880s or 1890s by which time the ruling nawab had moved to Ahmad Ganj, a relatively modest Indo-Gothic palace on a headland just outside Murud village, that remains private property today.

We could have spent hours here up on those great ramparts, a cooling sea breeze offsetting the hot sunshine. Local boatmen, though, seem loathe to spend more than an hour here unless you arrange a special charter. Weekends aside, when platoons of Mumbaikars come for fresh air, space and the beaches, you'll probably have Janjira virtually to yourself. Next time, I'll return with a picnic.

If you go

The flight

Return flights on Etihad Airways (www.etihadairways.com) from Abu Dhabi to Mumbai cost from Dh1,755, including taxes. From the Gateway of India pier, take a boat to Alibag. Once there, jump on the free shuttle bus to the town, where you can take a taxi or bus for the approximately 45km drive to Murud. Boats to Janjira leave from Rajpuri village, about 3km from Murud, and cost about 30 rupees (Dh2.5) per person, or from 400 rupees (Dh33) for private hire.

The hotel

Golden Swan Beach Resort (www.goldenswan.com) in Murud has double rooms from 3,100 rupees (Dh256) per night; cottages sleeping four cost 7,000 rupees (Dh578) per night. Hotel Nishijeet Palace (00 981 214 427 4158) has double rooms from 2,000 rupees (Dh165) per night, and a decent restaurant.