Stamps are dead, right? I mean, sure, they were fun while they lasted. But gone are the days when schoolchildren would eagerly snatch the mail from their parents and head for the kitchen kettle to steam off an exotic stamp from an overseas correspondent.

For a start, what with text and email and Facebook and all digital options in-between, who even gets or sends letters any more? And yes, post services around the world are experiencing a windfall from the Amazon home-deliveries revolution, but no one in those vast distribution warehouses is employed to lick the backs of millions of stamps – and no child today is patiently collecting the franking machine marks or prepaid postage labels that have taken their place.

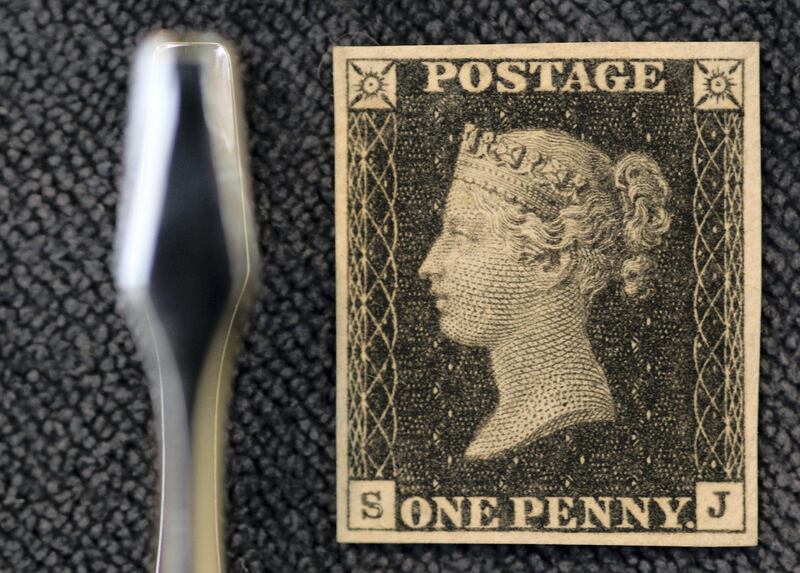

And yet, 178 years ago since the first adhesive postage stamp was issued – Britain's Penny Black, which came into use on May 6, 1840, bearing a profile portrait of Queen Victoria – fascination with the undeniable magic of stamps, tiny canvases that capture the social and historical nuances of their time, continues unabated.

The resurgence of stamps

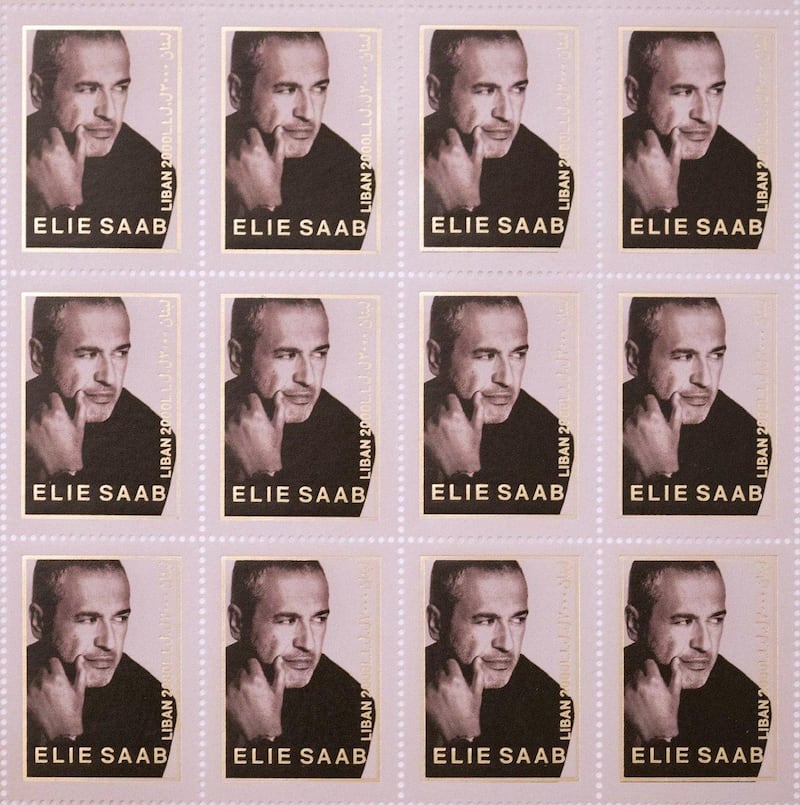

Evidence of that was seen at the end of March in Beirut, when LibanPost unveiled a stamp honouring the Lebanese fashion designer Elie Saab.

With boutiques and stores in countries from Lebanon to the United Kingdom, United States, France and the UAE, one might imagine that Saab, darling of the Hollywood red carpet and king of an international haute couture, ready-to-wear, accessories and perfume empire, might have better things to do than fly home just to see his face in miniature on a stamp. But not only was Saab at the Beit Beirut cultural centre in person for the launch of his stamp on March 31, he was joined at the unveiling by a flock of top-flight dignitaries, including Prime Minister Saad Hariri.

“It’s true that young people don’t write letters or really know what stamps are, and that, generally speaking, stamp collecting is for an older generation that is slowly dying out, so far fewer people collect stamps nowadays than they did in the past,” says Douglas Muir, senior curator of philately at The Postal Museum in London. “But people are still extremely honoured if they appear on stamps, and you get far more publicity about stamps in newspapers these days than you ever used to.”

Getting on a stamp

Until quite recently, appearing on a stamp used to be something of a double-edged honour. In most countries, unless you were the head of state, one crucial condition for being so honoured was that you were dead – and, preferably, that you’d been that way for at least five years.

In the UK, the birthplace of the postage stamp, the first living recipient of this honour was Sir Francis Chichester, whose boat Gipsy Moth IV, featuring its skipper's definite if unidentifiable image as a small figure on deck, appeared on stamps in 1967 in celebration of the sailor's singlehanded circumnavigation of the world.

Until then, the ban on picturing living people on stamps was an unwritten Post Office rule in the UK, and one that is still broken only rarely, and not always overtly.

A stamp in 1999 honouring Freddie Mercury, the singer with the band Queen, who had died eight years previously, also featured in the background the unmistakable figure of the band’s drummer, the very-much-still-alive Roger Taylor. But the tribute of the first starring role as a living subject on a stamp was reserved for cricketers Michael Vaughan and Freddie Flintoff after England’s victory over Australia in the Ashes series in 2005. In the US, a statutory restriction on the use of portraits of the living on currency, dating from 1866, was also applied to postage – until in 2011, the United States Postal Service announced it was “dropping a rule that currently requires an individual to have been deceased at least five years before being honoured on a stamp”.

In a move that looked suspiciously like a cynical effort to make philately both cool and commercially viable again, members of the public were urged to use social media – ironically – to nominate “acclaimed musicians, sports stars, writers, artists and other nationally-known figures” for consideration as subjects for stamps.

Appealing to a new generation

Stephen Kearney, manager of stamp services there, was frank about the motivation behind the move. “Engaging the public to offer their ideas,” he said, was “ an innovative way to expand interest in stamps and the popular hobby of collecting them.”

Many US stamp collectors were aghast when a set of “living” stamps in 2013 featured not famous Americans, but the all-British cast of the Harry Potter films.

“It’s all about money, of course,” wrote US blogger, journalist and stamp enthusiast Jeff Stage. He said the postmaster-general “hopes stamps like the Harry Potter set will prompt more people, especially young people, to buy stamps, and maybe even save some … [but] how many young people have you seen hanging around a post office just giddy in anticipation of when the next stamps will come out?”

Giddy or not, the trend for producing stamps deliberately with collectors in mind explains why the postal services of so many countries now honour the living – even the fictional “living”.

“Certainly the use of stamps is far less than it was, even in the fairly recent past, and is slowly declining,” says Muir. “But in the UK, for instance, the Royal Mail now uses stamps largely to raise revenues from collectors – not just stamp collectors, these days, but from collectors of particular types of memorabilia. ‘Collectibles’, issued in connection with films, such as Star Wars, are not really aimed at stamp collectors at all, but at people who are interested in Star Wars.”

Who should be on a stamp?

There are, he says, hazards attached to putting live people on stamps. Sportspeople tend to be covered with advertising, and “if somebody’s still alive they can still go and commit offences of one kind or another, which is not the sort of person you’d want on a stamp”.

In 2000, Australia issued “instant” stamps to commemorate its gold medallists at the Sydney Olympics, the day after their victories. Greece followed suit in 2004, but the Greek postal service was forced to withdraw a stamp issued to celebrate the bronze medal won by weightlifter Leonidas Sampanis after he failed a drugs test.

Whether the story they tell is good or bad, there is no disputing the historic, political and social significance of stamps as tellers of tales and flag-bearers of national identities and cultures. Far better, perhaps – or safer, at least – to stick to reliable living subjects, such as heads of state. But even the story of how local leaders were first portrayed on stamps in the Gulf, episodes that illustrate the tensions between a post-colonial Britain and the countries then still under its influence, is not without its drama.

Until 1948, the handful of postal agencies in the Gulf were mainly run from British India. The first in the Gulf, in Muscat, was set up in 1864. Following Indian independence in 1947, the agencies were operated from Bahrain by the British Post Office in London.

Stamps in the Gulf

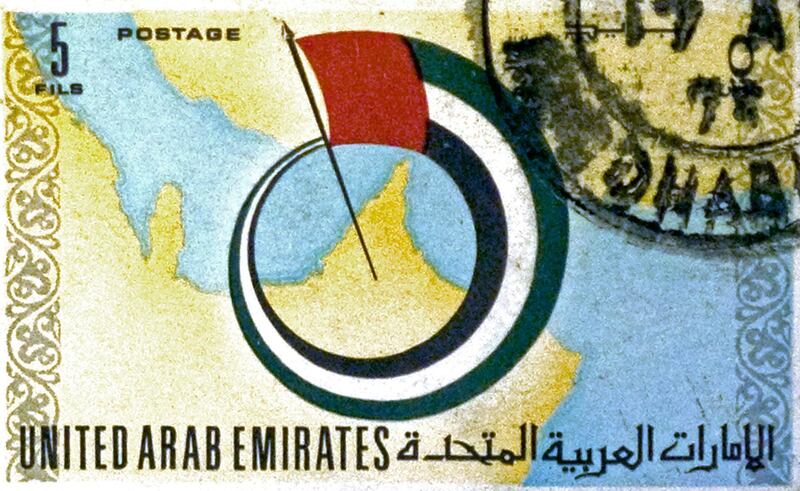

In the former Trucial States (which became the UAE in 1971), an agency opened in Dubai in 1909, followed by one in Abu Dhabi in 1963, and at first, the individual emirates used stamps produced for India or Great Britain, often overprinted with local place names.

Documents from the archives, now held by The Postal Museum, reveal that in 1946 Sheikh Salman of Bahrain began lobbying the British to be allowed to set up his own postal service, using stamps bearing his image.

The sheikh’s strong feelings on the matter were conveyed to the British Political Agent in Bahrain in a letter from Sir Charles Dalrymple Belgrave, adviser to the ruler, to the British political agent in the region in 1950.

The fact that British stamps were used “gives the impression to all, except the few who happen to be aware of the situation, that Bahrain is a British possession”, Belgrave wrote. “His Highness believes that it is not the wish of the British Government that this wrong impression should exist.” Instead, he “would like Bahrain stamps to bear an individual design with a portrait of himself upon them”.

Such was the perceived political sensitivity of the issue in Britain that the request went all the way to the top – to King George VI. His majesty, the Foreign Office informed its man in Bahrain, had no objection, provided the stamps were limited to internal use, but “considers it may be wise to go extremely slow in this matter, particularly if the issue of such stamps is to be taken as a precedent by the other States in the Gulf”. Slowly was how it went: it would be 1953 before Bahrain finally had a stamp featuring its ruler, and then only for internal use.

____________________

Read more:

Commemorative stamp issued to mark Sheikh Zayed Heritage Festival

March Project at the Sharjah Art Foundation

Emirates Post issues stamps to mark UAE's Year of Giving

____________________

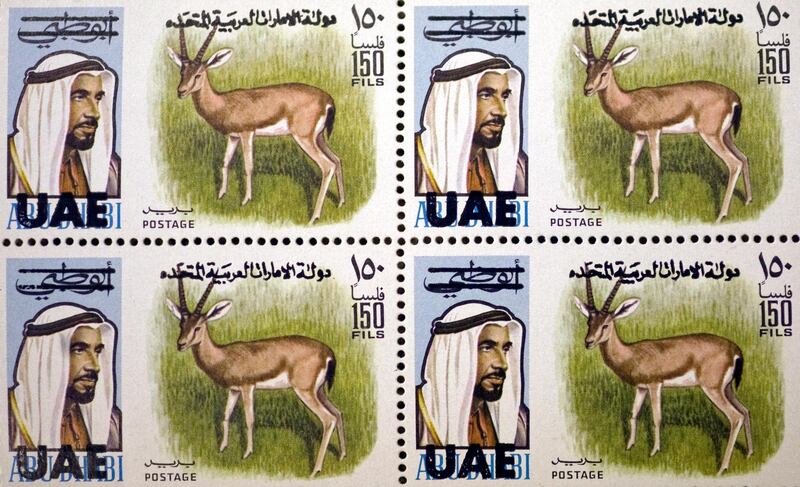

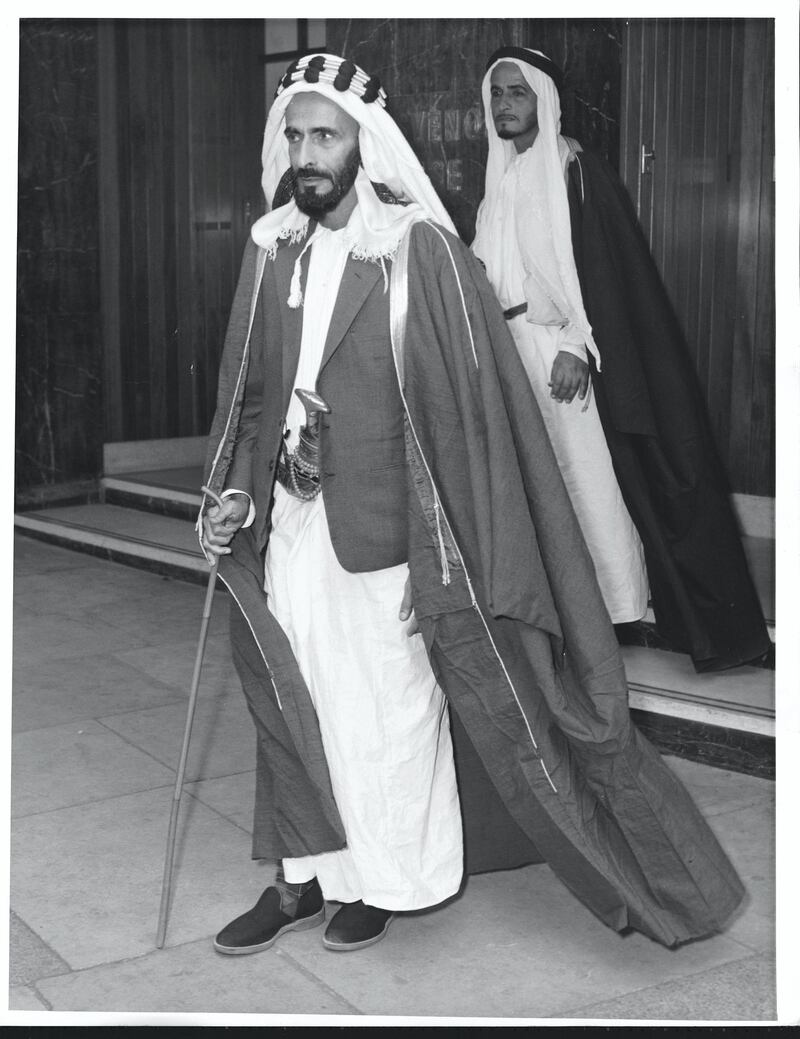

Abu Dhabi Ruler Sheikh Shakhbut bin Sultan also decided he wanted his own stamps. Archives in The Postal Museum reveal he began campaigning to get them in 1959 – and "when once he takes an idea into his head, he is as tenacious of it as any other man I have ever met", as the political agent in Dubai wrote to the Foreign Office in London. It took him almost five years but Sheikh Shakhbut prevailed. After much to-ing and fro-ing between London and Abu Dhabi, a set of four stamps was released on March 30, 1964, but not before careful consideration of the niceties surrounding the portrayal of the sheikh.

The Postal Museum holds the original artwork and “essays” – mock-ups of trial stamps – for many of the stamps produced by the British postal agencies in the Gulf. On the one-rupee value stamp, a Post Office memo noted, “we cannot accept the placing of the Ruler’s portrait in the branches of the palm … the tree should be moved to the right hand side of the stamp”. While they were at it, “we should also like to see the palace” – the 18th century Qasr Al Hosn, then the ruler’s residence, now surrounded by the modern capital – “made a little larger”.