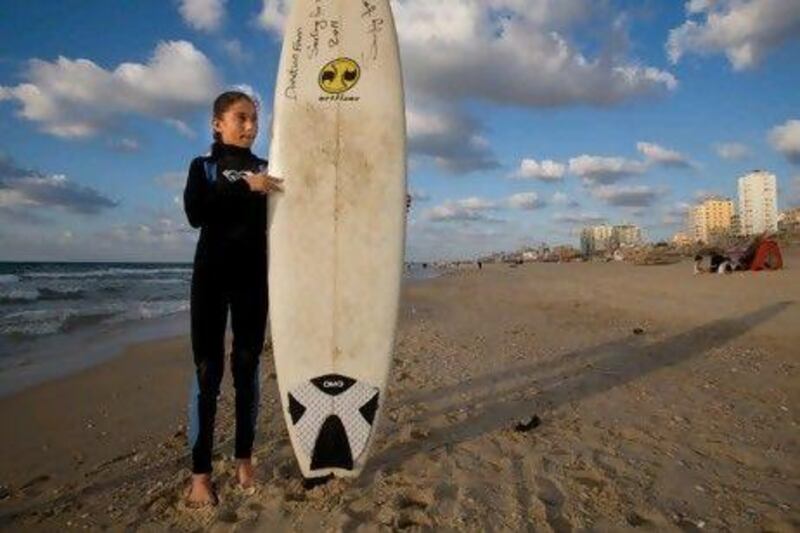

There are few surfers in the Gaza Strip, and fewer still are female. One of them is Sabah Abu Ghanim, who loves the joy and the freedom of the sea. But, as Rebecca Collard learns, the 12-year-old realises that cultural and social norms may bring an end to her riding the waves.

Sabah Abu Ghanim's brother carries her new surfboard across the seaside road that separates her family home from Gaza's Mediterranean coast. The board - donated by an American surf group - is two feet taller than 12-year-old Sabah.

She slips her board into the water and wades out towards the small, barely curling waves. Outfitted in a professional black-and-blue wetsuit, she pushes the board deeper into the sea and waits for a strong wave to propel her long enough so she can stand up on it.

Good surf on Gaza's beaches is rare - the larger swells occur in the colder, winter months - but Sabah comes in search solely of big waves.

"There is a connection between me and the sea, and there, for a little time, I feel happy and free," the seventh-grader says, pulling on her braided ponytail. "It belongs to me, and I belong to it."

In the summer, Sabah comes almost every day to surf the sea across from the tall apartment blocks that line the coast of the densely populated Gaza Strip. Many of the buildings still show scars of the war here almost three years ago and of some more recent Israeli air strikes. Sabah says now that school has started again, she can make it to surf only on Fridays.

Surfing is rare for females in Gaza's conservative society and besides Sabah, her sister and her cousin, few females have tried it. But Sabah learnt from her father, a longtime surfer, swim instructor and lifeguard on the Gaza City beach.

"When I was little I saw my father surfing," she says, sitting in her family's breezy summer room with thatched roof and striped, multi-coloured curtains facing the Mediterranean. "I was 8 years old. He taught me how to swim and then slowly how to use the board. I loved it."

The sea has always been cherished by the people of the Strip, a mix of native Gazans and refugees from coastal cities to the north such as Jaffa and Ashkelon in what is now Israel.

"The people that live beside the beach like to swim and fish to do many things in the water," says Mahfouz Kabariti, the president of the Palestine Sailing and Surfing Federation. "At first they rode the waves with their bodies and built something called shayyata in Arabic - boards made by hand from wood."

But eventually Gaza's surfers, such as Sabah's father, Rajab Abu Ghanim, saw US surf shows and were inspired by the Americans.

"I saw it on the television, but nobody was doing it like that here," says Abu Ghanim, wearing a surfer's board shorts, tight-fitting T-shirt and beanie cap with long hair tucked out the back. "So I bought a used surfboard from Tel Aviv for 150 shekels. I'm so faithful to my board. I still have it after 20 years."

Before the start of the second intifada a decade ago, thousands of Gazans crossed daily into Israel for work. Some started learning from surfers there and brought boards back from Tel Aviv, where surfing had long been popular among Israelis.

Other Gazans would see the surfers in the sea off Gaza City and ask to join. There are now around 35 surfers in the club ranging from children to men in their late 40s.

But as tensions rose with the outbreak of the second intifada, Israel stopped allowing workers to enter Israel. After Hamas took full control of Gaza in 2007, Israel shut the gates of the tiny coastal strip almost completely.

Now, getting even small boats for kids into Gaza is difficult because of Israeli security procedures, says Kabariti. And Gaza lacks the equipment, materials and technical skill to make surfboards and lightweight boats in the Strip. Even surf wax is hard to come by.

Gazans' use of the sea is limited to three nautical miles, making fishing and sailing nearly impossible. Israel says the blockade is necessary to stop the infiltration of militants into Israel and arms importation to Gaza. Earlier this year, Israel stopped a boat filled with Iranian artillery in the Mediterranean.

"They say it is for security reasons but it is not reasonable. We can't accept it. It's collective punishment," says Kabariti. "Three miles is not even enough for leisure."

Kabariti says that for the people of Gaza, particularly children, leisure is crucial after years of occupation, blockade and bombardment. According to a study commissioned by the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization earlier this year, 83 per cent of Gazan schoolchildren reported feeling nervous, and more than 70 per cent suffered from nightmares and fear another war.

"Here, we go from intifada to intifada. Always a struggle. Always waiting for a solution," says Kabariti. "Especially after the siege, many people lost their work, and after the last war the kids and the teenagers need to feel freedom, even for a little time."

After a report on them appeared in a US newspaper, Gaza's small but distinctive legion of surfers caught the attention of some of America's big-time boarders. In 2007, the Jewish-American surfing legend Dorian Paskowitz read about Gaza's surfers and their board shortage. He became determined to bring them boards from the US. But when he arrived at the Erez crossing between Israel and the Strip, Israeli border guards said he could not enter and the Gazans could not come out to get the surfboards.

"Eventually, he talked them into it," says Kabariti, and Gaza had a dozen new, professional boards. Before this, most of Gaza's surfers shared a handful of boards or used styrofoam floaters to ride the waves.

Sabah was among them. She points to a meter-long blue board that she often used until recently. Now, she says, with a proper board of her own and the wetsuit donated by the US-based Surfing for Peace, she can train to a professional level.

"I want to travel outside and participate in competitions - and to win a competition," she says. "I want to go to America. I see girls on the television - and boys - and I can learn things from them."

Unfortunately, Sabah's chances look slim.

Her 14-year-old sister, Shoruq, also once rode the waves of Gaza. But her father explains that people started to watch and criticise her. Shoruq sits on the opposite side of the table, wearing a loosely pinned black headscarf, a long-sleeved shirt and jeans, next to a window that looks out on the Strip's ever-stretching sandy coastline.

"I see my smaller sisters and cousins going to surf. I really hope I can go again but because our society doesn't accept that, what can I say?" says Shoruq, who has just crossed the line from being seen as a girl to something closer to an adult.

While girls and women can be found frolicking on Gaza's beaches in the hot summer months, they do so fully covered and in shallow waters. Sports are something typically left for men, and few Gazan women know how to swim.

"One day I went to the sea with my girlfriends from school in the boat," says Sabah. "I dived into the water. They were surprised. 'How can you do this?' they asked me. My friend was interested and I tried to encourage her. I got her a life jacket and said: 'You have try. You have to learn to swim.'"

But Sabah can't train them all, and Kabariti says that while he believes people could accept female swimmers and surfers, the Strip lacks female instructors. "Only Sabah and these girls have a chance to learn because their father is interested so he can teach them," he says.

Sabah is trying to change that. "My friends don't know how to swim. I try to get them to learn to swim so they can also surf," she says. "I want them all to come with me to the sea."

Kabariti says there also aren't enough training suits for women and girls, as in Gaza they require a special suit sleek enough to surf but that still adheres to cultural and social norms by covering the body and the hair. Sabah, Shoruq and their cousin Kholoud, 15, had suits donated as well, but even with the special attire, Abu Ghanim says the two older girls attract too much attention.

"I want her to go to the sea," he says of Shoruq. "I want all my daughters to go." (He has two girls younger than Sabah, along with four boys.) If the beach is empty, he sometimes takes Shoruq to surf. "I want her to have the chance, but I'm worried society will not accept her."

In this relatively closed and close-knit community, the perception of others can mean a lot for a young woman's future. For Sabah, it's a prophecy that her joy and freedom in the sea will soon end. But even at 12 she seems to understand the complication.

"I want to continue with surfing, to compete," she says, and adds that if she can't be a professional surfer she'll consider being a teacher or a doctor. "But when I'm older I won't be allowed. The people here don't accept it."