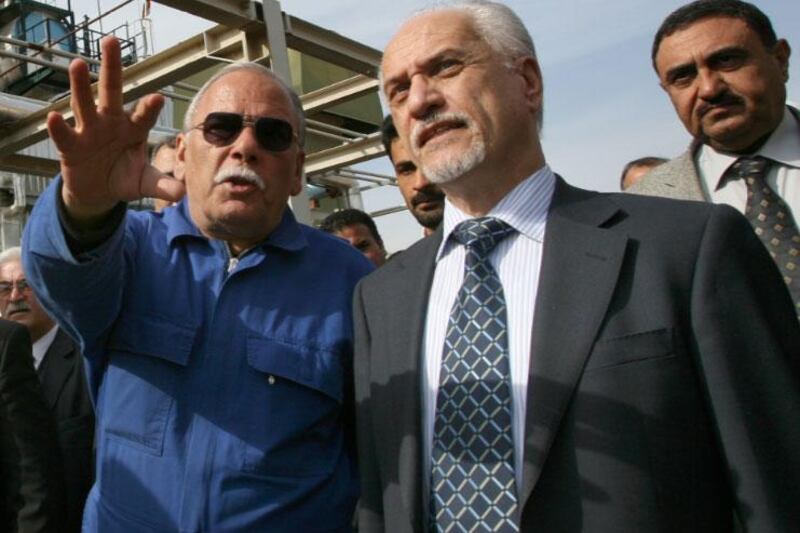

Dr Hussain al Shahristani has piercing blue eyes and the silvering remains of a head of wavy fair hair. The soft-spoken Iraqi oil minister, a devout Shiite Muslim, is also reputedly incorruptible and has more been sought after by men in power than a power-seeker himself. It is those latter qualities that in May 2006 led Iraq's prime minister, Nouri al Maliki, to pick Dr al Shahristani for one of the most important and difficult jobs in his cabinet: resuscitating the country's ravaged oil and gas sector to help Iraq realise its potential as a world-class energy producer.

With parliamentary elections looming against a backdrop of rising Iraqi nationalism as US troops pull out of the country, that task has seldom seemed more daunting. Last year's steep slide in crude prices from their record peak of US$147 a barrel hit Iraq's oil-dependent economy hard, exacerbating the lack of government funds that Dr al Shahristani had identified as a major impediment to development.

Under intense pressure to reverse production declines from big oilfields, the minister staked his political future on an auction of oil contracts to foreign firms - the first since Iraq's late dictator, Saddam Hussein, had kicked them out of the country in 1972. The gambit was at best a limited success. Last month's auction in Baghdad, broadcast live on TV, ended with the ministry bagging an agreement with BP and China National Petroleum Corporation to boost output from Iraq's biggest oilfield by an impressive 1.85 million barrels per day (bpd); a volume exceeding the current oil production of Libya.

But nearly 30 other bidders snubbed the remaining seven deals Dr al Shahristani offered, baulking at the government's maximum payment terms. Many observers doubt Dr al Shahristani can get his oil programme back on track, casting doubt on his continued tenure as oil minister. "It's been nearly 40 years now that Iraq has failed to live up to its oil potential," says Daniel Yergin, the chairman of the oil consultancy IHS Cambridge Energy Research. "It's not a foregone conclusion that these arrangements will, in themselves, do what needs to be done."

Dr al Shahristani was already fighting for his political life before the auction. Just before it was launched, he was summoned before parliament to face two days of questioning. Managers and engineers at Iraq's South Oil Company (SOC), the biggest of the country's three state oil producers, had staged a revolt, calling for the bidding round to be cancelled. And the regional government of Iraqi Kurdistan, at loggerheads with Baghdad over territory and oil jurisdiction, had stepped up demands for the oil ministry to recognise more than a score of oil and gas deals it had signed with foreign firms, and which Dr al Shahristani had declared illegal.

Despite these challenges, the 67-year-old oil minister remains one of the Middle East's most powerful politicians, presiding over a process that could more than double Iraq's oil production to 6 million bpd, which would make the country the world's second-biggest oil exporter after Saudi Arabia. He turned down a chance to be Iraq's first post-war prime minister in 2005, although he was favoured by the UN envoy Lakdar Brahimi, and with the ear of the Grand Ayatollah Ali Sistani, the country's most powerful Shia Muslim cleric.

"I have always concentrated on serving the people and providing them with their basic needs, rather than party politics," Dr al Shahristani said, explaining why he did not want the job. Born in 1942 in the Shiite holy city of Karbala, south of Baghdad, the young Hussain showed an exceptional aptitude for science in secondary school, and was encouraged by Iraq's revolutionary government to pursue higher education abroad.

He earned a double doctorate in Canada, where he also wooed and married Bernice Holtom, the woman who typed his thesis. In 1970, Dr al Shahristani returned to Iraq with his wife and spent the next decade working at the Iraqi Atomic Energy Commission, eventually becoming its chief scientific adviser. That ended on Dec 3 1979 when Dr al Shahristani was removed from his job after opposing a directive from Saddam to begin extracting plutonium for the production of nuclear weapons. Shortly afterwards, he was arrested on a number of trumped-up charges, including assisting Shiite dissidents and collaborating with Israel. In Feb 1980, he refused to implicate a colleague under torture and was sentenced to 20 years in Abu Ghraib prison.

Commenting on his torture and imprisonment, which included years in solitary confinement, Dr al Shahristani said he was "luckier" than many other prisoners because he did not experience or directly witness some of the more extreme forms of torture used by Saddam's regime, and because his family was not harmed. The US bombing of Baghdad at the start of Operation Desert Storm in 1991 threw the Iraqi capital into disarray and gave a small group of Abu Ghraib inmates a chance at escape.

Assisted by a guard, Dr al Shahristani donned the clothes of an Iraqi Intelligence Service officer and made off in one of the service's official cars. Unchallenged by security personnel, who were forbidden to interfere with the intelligence service, he collected his family and fled first to Kirkuk, then to Suleimaniya in Kurdish Iraq. After briefly joining the unsuccessful Kurdish/Shia uprising against Saddam, he joined the exodus of Iraqi refugees to Iran. With his wife, he established the Iraqi Refugee Aid Council (IRAC) and for the next few years the couple shuttled between Tehran and the UK, working for aid organisations.

Two days before Saddam's regime fell in April 2003, Dr al Shahristani returned to Karbala and established a branch of the IRAC there. But troubles began shortly after his appointment to the cabinet of Iraq's first elected government in 2006. As Iraq's security situation deteriorated that year, due to increasing sectarian violence, militant attacks on the country's energy infrastructure hampered efforts to alleviate fuel shortages. Dr al Shahristani, as the man in charge of the country's oil and gas resources, became a magnet for blame.

In the meantime, he drafted a federal oil law that the US strongly supported. The American enthusiasm sparked a backlash among populist members of Iraq's parliament, who accused him of colluding with western oil companies to give away the country's resources. Kurdish politicians also opposed the new law, saying it gave Baghdad jurisdiction over several oilfields located on disputed territory. The law remains in limbo, placing any deals the oil ministry signs with international companies on shaky legal ground.

Despite the recent start of limited oil exports from Kurdistan, Dr al Shahristani's dispute with the Kurds is also unresolved. The exports may not continue for long if Baghdad and the Kurds are unable to come to terms over payments to the Turkish, Canadian and Norwegian companies pumping the oil. Considering his sojourn in Suleimaniya as a fugitive from Abu Ghraib, Dr Shahristani could hardly be insensitive to Kurdistan's urgent development needs.

For decades, Saddam's regime neglected oil development in the region, allowing fields in Iraq's Arab-controlled southern areas to pump all the oil allowed under the country's OPEC quota. Iraq is still a member of OPEC but is exempt from output restrictions in order to give the country a chance to rebuild its shattered energy infrastructure. Taking advantage of this opportunity, Dr al Shahristani has tried to speed up some of the most pressing oil and gas projects in Arab-controlled regions, through the bidding rounds and by pursuing direct deals with foreign partners. But little has been done for the Kurds, as the oil minister has shown no proclivity for compromise.

Ironically, Dr al Shahristani and the Kurds agree on the main issue that has set the minister at odds with Iraq's oil unions and many of its parliamentarians and technocrats. They acknowledge the country needs western oil companies' technology to boost output from its damaged reservoirs and to discover oilfields. At the same time, the oil minister and his critics at SOC agree that pervasive red tape and Iraq's cumbersome political process have been hampering progress, although they differ on who is to blame.

"I find it strange that explosives and drugs are moving through the borders, but when it comes to equipment of the Iraqi oil ministry we face obstructions," Dr al Shahristani said this year. But as Iraq gears up for its national election in January, compromise on key energy issues seems further away than ever. Given that Iraq derives 95 per cent of state revenue from oil, those issues seem destined to dominate the election.

And Dr al Shahristani, until now a consummate survivor, could be defeated by the compatriots he wanted to help.

tcarlisle@thenational.ae

Iraq oil minister Shahristani staked future on oil auctions

Dr Hussain al Shahristani, the oil minister of Iraq, is reputedly incorruptible, a quality he needs in negotiating a new regime of contracts with producers.

Editor's picks

More from the national