ATHENS // Despite the sky falling in for many Greeks, the country’s space technology sector is going from strength to strength.

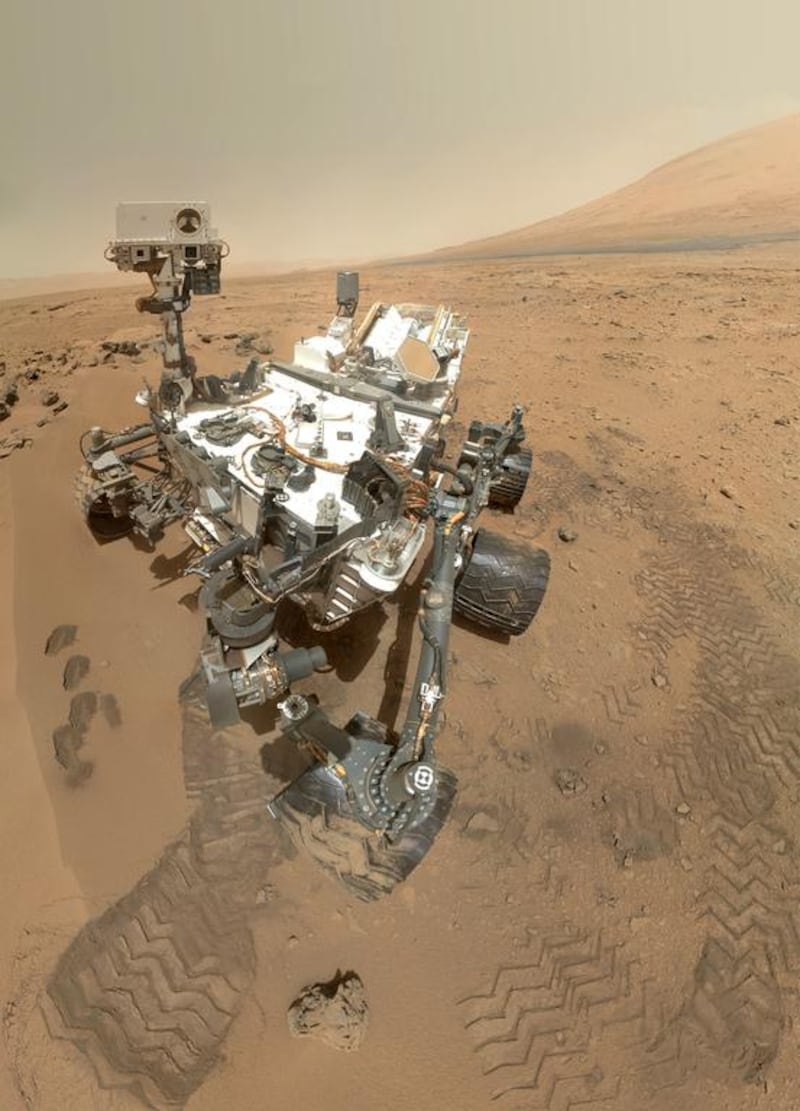

When the Nasa Curiosity rover landed on Mars in 2012, the world was enthralled by the detailed images of the Red Planet which it relayed back to Earth. What very few realised was that behind the images was a Greek company, Alma Technologies, and more specifically their Jpeg Encoder Intellectual Property core inside the rover’s Malin Space Science Systems (MSSS) camera. The photos were compressed using this technology for easier delivery in the low bandwidths space transmissions use.

Behind the curtain of Greece’s political and economic turmoil, a technology sector that few expect to find here is not only growing, it is actively looking for investment.

“When we meet people at international expos they are very impressed,” admits Christos Kyriazoglou, the director of business development and marketing at the Integrated Aerospace Sciences Corporation (Inasco).

“Greece doesn’t have the branding of a high technology country; especially in the case of aerospace. People think Greece is all about traditional agricultural products like feta and olive oil, or, tourism and hotels. But that’s not the case.”

Located in the pretty suburb of Glyfada, known for its elegant cafes, Inasco is one of a growing number of Greek companies that is excelling in space-related technology in both Europe and beyond.

Inasco was established in 1989 and follows a business model of “smart specialisation”. It has three main areas of focus: aerostructures, composite technologies, and space systems. It is this last area it has been focusing on growing in recent years.

The company recently won a contract from the European Space Agency (Esa) to develop electric propulsion technology for microsatellites, a next-generation technology that foresees applications such as satellite constellations, sparked by increasing demand for global Web coverage.

But this is not the only enabling technology Inasco is working on. The company is also developing aerospace technologies such as space qualified photonics integrated electronic circuits, which can be used to speed up and increase reliability in satellite communication systems; and composites for space satellite structures such as nanocomposites and graphene reinforced composites. All the above are entirely designed and manufactured in Greece.

Like all Greek space technology industries, Inasco is 100 per cent externally focused.

“Space technology is capital intensive, capital which is not so easy to come by in Greece. To go into serial manufacturing you need a lot of capital. So we’re always looking for alternatives in corporate financing such as strategic investments,” says Mr Kyriazoglou. Its search extends to markets such as the UAE with its fledgling space programme and well-established aerospace industry.

But Mr Kyriazoglou is also keen for his own government to invest more heavily in Greek space technologies.

“If you focus only on high consumption goods like olive oil or feta, it’s hard to maintain long term growth and sustainability,” he says.

“Technology has these [sustainable] characteristics. That’s why we are trying to convince the government to put their focus on the high-tech industry because there’s a lot of added value here.

“Space has a high ROI [return on investment] and enabling technologies also fosters change, which in turn fosters job creation. This is an effective way to reduce the ‘brain-drain’ effect that Greece is currently experiencing.

“Highly skilled Greek engineers and scientists that have migrated to foreign high-technology markets can come back to Greece because of the opportunities that we are creating back home. If you want to create opportunities you have to think outside-the-box; there are no opportunities inside the box,” Mr Kyriazoglou adds.

On the other side of Athens, Emmanuel Zervakis, the general director of European Sensor Systems (ESS), lays out prototype satellite sensors that are part of an Esa contract which the company recently won, and which resulted in the design of a pressure transducer for space applications based on Mems (micro electro mechanical systems) technologies. These are tiny sensors built on silicon wafers, so small that they can literally fit on a pin head. ESS designed them from scratch and is the only Greek company that produces them.

Size and weight being a factor in space, Mr Zervakis explains the intended use of the Mems chips as part of a contract with Thales Group. The chips will eventually sit inside a titanium housing – also designed by ESS – which attaches to the side of a satellite and monitors the satellite’s propellant.

“A satellite’s lifespan is 15 to 20 years. A pressure sensor connected to the propellant tank measures the remaining propellant, which usually is very accurate at the start of the satellite’s life but not at the end due to the harsh environment of space,” Mr Zervakis says.

It is important to know how much propellant is left in the tank because at the end of a satellite’s life, it needs to be manoeuvred correctly to burn up in the Earth’s atmosphere. If the sensor is wrong, the satellite will either be destroyed too early and need an immediate replacement, or will run out of fuel and become stuck in space (space debris), incurring hefty fines. Both are expensive miscalculations.

“The biggest advantage for Mems are the small size, thus weight, the lower power and of course lower cost,” says Mr Zervakis.

“The trend is nowadays to shrink the dimensions of the satellites going toward micro satellites, which can be achieved through Mems technology.”

Along with Theon Sensors, ISI Hellas and European Finance Associates, ESS is part of the European Finance Associates group of companies (EFA group), which includes the UAE in its list of 45 clients it has exported to. It has also had a presence in the UAE with an Abu Dhabi office since 2011.

Products exported to the UAE include electro-optic systems such as night vision monoculars and binoculars.

ESS started life as Theon Sensors in 2004. After Greece joined the Esa in 2005, an Esa task force visited to the country to identify promising companies to work with.

Theon Sensors was one of the companies that was identified as having strong potential as part of this process, especially its sensor technology at the time.

For companies in regions it is interested in, Esa operates an approximately five-year incubation period to bring the local industry to a European standard, after which these companies compete in pan-European tenders for projects.

“The first contract with Esa in 2007 was to carry out a study and design a Mems accelerometer and to see if we can serve space applications through it. Esa gave us five different case studies and scenarios to simulate. We simulated these environments and we proved that indeed we can address these environments,” says Mr Zervakis.

“At the end of this contract, the Esa introduced us to Astrium in 2009, which is now [part of] Airbus. We got another contract with them, and that contract was to take the accelerometers from the first contract and make a differentiation towards Astrium applications, namely measuring the vibrations of a launch procedure.”

ESS won its third Esa contract through an open tender process after it branched out from Theon Sensors in 2012 and its five-year mentoring period came to an end. This is its current contract with Thales group.

There are three types of products ESS is working on: accelerometers, pressure sensors, and flow sensors. Beyond space, these applications can find other industrial uses, too.

“Accelerometers can monitor the vibrations of a launch procedure but they can also monitor the vibrations of an oil exploration platform, or the vibrations of buildings due to earthquakes. An accelerometer in the engine of a ship can monitor the vibrations of the engines and identify problems early on,” Mr Zervakis points out.

With its rapidly expanding space technology sector, the country has come a long way in just 10 years.

Mr Zervakis laughs as he recalls the initial efforts at getting backing from the government to create a local space programme. “We went to the local authorities and initially they thought we were talking about UFOs. They weren’t joking.

“In the last few years we’ve been communicating to our politicians that space technology is an industry that can keep engineers in Greece. If you invest in space, you will get five times the return.

“Now they are starting to hear and hear and support us.”

The country’s economic crisis has had a widespread impact and the space sector is no exception as companies such as ESS fight to show Greek engineers that good opportunities exist at home.

“The level of Greek engineering is very, very high,” says Myrto Papathanou, who heads corporate development at the EFA group.

“There needs to be a way to keep those people here and help them develop as engineers and scientists on the cutting edge of technology.

“Why does it have to be the usual story of someone leaving Greece and then excelling in their field?” she asks.

The issue of Greece’s image problem abroad has impacted Greek firms, too. “Many times customers don’t have a problem with our technology or performance but express concerns about the instability here,” says Mr Zervakis.

“We could move out of Greece, but we want to stay. Engineers in Greece are excellent so it’s a strategic decision for us to keep the company here.”

According to Athanasios Potsis, the president of the Hellenic Association of Space Industry (Hasi), which was formed in 2008, Greece exported €200 million (Dh800.9m) of space industry products in 2015.

About 40 Greek companies fall under Hasi’s umbrella, employing about 2,500 highly specialised staff. The association was created to help to develop and promote the Greek space industry at home and abroad.

“The Greek space industry exists because of the government’s decision in 2005 for Greece to become the 16th member of the Esa,” says Mr Potsis.

Since Esa only funds its own missions, the decision was taken to create a local space programme, called the Industrial Space Cluster (SI Cluster), which brings together the space industry and the country’s universities and was funded by the Europe-wide National Strategic Reference Framework (ESPA).

“Recently we’ve been trying to create international cooperations in Germany, Italy, Holland, Canada to create joint ventures,” says Mr Potsis.

“The UAE is also of interest to us and we already have a presence there through Aerospace Ventures AG Abu Dhabi. Aerospace Ventures represents three companies, ESS, Theon Sensors and ISI Hellas and has core capabilities in space products and services.

“They act as ‘Made in Greece’ ambassadors for the development of a cooperation plan between the space industries in the UAE and Greece,” he adds.

That Greece’s relatively new space technology sector even exists, let alone thrives, is down to Athens’s determination, says Mr Potsis.

“The fact that there is a Greek space industry at all is down to the government’s decision to join the Esa. The SI Cluster is managed by the ministry of education and the general secretariat for research and development,” he says

“We’re going through a very painful economic crisis and the basic issue for us is that we’re losing very highly qualified engineers. This is bad for us.”

business@thenational.ae

Follow The National's Business section on Twitter