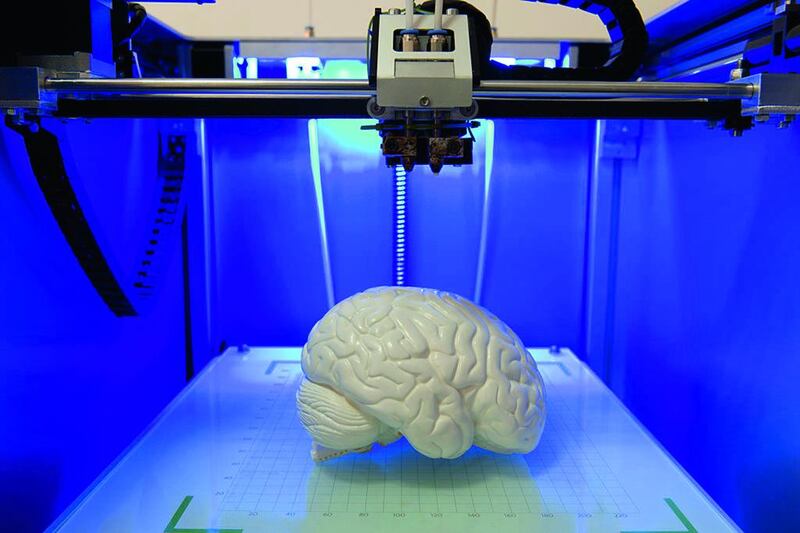

Three-dimensional printing may still seem more like science fiction than real-life science, but its use in the medical world is booming, with the number of 3-D printers doubling year-on-year.

Traditional prosthetic hands, for instance, can cost anywhere from US$6,000 to $40,000 (Dh22,000 to Dh146,900), but 3-D printing is allowing volunteer groups such as the global, web-based Enable Community Foundation in the United States to offer their bionic “Raptor” hand for free and to print it within a couple of days.

For the two million hand amputees in the world, including children who outgrow their artificial limbs far too quickly, this is life-changing. Even veterinarians are beginning to use the technology. Earlier this year, a mutilated toucan bird in Costa Rica was given a new 3-D-printed prosthetic beak.

The technology, also known as additive manufacturing or rapid prototyping, turns digital models into solid objects, printed in successive layers of materials such as glass, metal, plastic or ceramic. The mechanism has been available since the 1980s, but printers became much cheaper after a 2009 patent expired.

Costs have dropped rapidly and, according to consultants Frost & Sullivan, the healthcare industry is now driving the growth of 3-D printing, which will become a $6 billion market by 2025.

Research firm Gartner calculates that up to 500,000 3-D printers have been shipped worldwide this year. The figure will more than double each year, it estimates, to reach 5.6 million 3-D printers in 2019. 3-D printing has the potential to “revolutionise” a number of sectors, including health care, says Dr Thomas Bartel, section head of the Heart and Vascular Institute at Cleveland Clinic Abu Dhabi.

“In health care, 3-D printing’s most impressive function is its ability to replicate organs to help plan for or simulate surgeries,” he says. “3-D printing helps us personalise care while minimising risk.” The clinic is one of the few hospitals in the region to use the tool for heart surgeries and catheter-based interventions.

“Everyone has a unique anatomy,” says Bartel, “and in complex procedures, where we perform surgery in hard-to-reach areas around the heart, 3-D organ replicas are highly accurate and serve as a helpful aid for procedural planning.

“The 3-D model shows separation of cardiac and vascular structures from the surrounding tissue, giving us clear sight of any target region and what to expect in the operating room.”

These models can also be used post-surgery to identify any “adverse outcomes”, such as if a valve implant was not inserted accurately, says Bartel. They can even be wheeled into the operating theatre during surgery, to be used by the surgeon as a live, visual aid.

Ahmad Mackieh, chief executive of Abu Dhabi-based 3DCreations, has full-colour printers, wax printers (which print parts in wax to be cast in alloy metals) and stereolithography (SLA) printers, which deliver resin-based materials and have been used by 3DCreations to make dentistry moulds.

“Bones can be replaced by printed parts by fixing them directly – if the printed material can be accommodated by the human body – or by casting the element out of the printed part,” he says.

“Some hospitals these days examine 3-D printed parts that simulate fractures in a bone or skull, and research centres are developing tissue 3-D printing that can reconstruct the face, nose or ear.”

US- and UAE-based Medativ, one of 30 companies recently chosen by the Dubai Future Accelerators programme to work directly with the Government – in this case, the Dubai Health Authority – creates patient-specific anatomical models.

Founder Mohamed Elawad says 3-D use has been “limited” in the UAE because of a lack of awareness and because 3-D models are not reimbursed by health insurance. But, he says, Japanese insurance firms have now started to cover costs, which is a “good sign”.

“Once the clinical and economic benefits of using 3-D printing in medicine are better quantified, and physicians are more aware of the technology, I believe you will see widespread use,” he says.

It is likely to start being used in universities in the place of cadavers, he says, adding that 3-D printing offers “affordable, personalised solutions” for patient-specific implants, prosthetics, bionics and orthotics.

Other medical uses are also emerging. In 2014, neurosurgeons in the Netherlands made the first successful implant of a 3D-printed plastic skull in a 22-year-old woman with a rare bone disease, whose skull had thickened from 1.5cm to 5cm, destroying her vision.

And last year the US Food and Drug Administration approved epilepsy pill Spritam (levetiracetam), the world’s first 3-D printed medicine. The tablet is made by layering powder with printed drops of liquid to make a high-dose drug that can dissolve rapidly.

It may not be long until the pharmacy is dispensing your medication hot off the printing press.