On most days, Pamela Gale Malhotra, co-owner of the Sai Sanctuary private forest in India, is fast asleep at 1.30am, after her typically full programme of organising walking safaris and animal feeds, and checking camera traps for signs of poaching. But a few years ago, Pamela and her husband, Anil Malhotra, woke up to the sound of trumpeting elephants. They assumed – rightly – that a baby elephant must have strayed too close to a partially covered pit and fallen in. As her husband switched on the rarely used floodlights and prepared to call on their neighbours for aid, Pamela stepped out to a magnificent sight. Dozens of elephants from the Sai Sanctuary's herds, as well as the neighbouring Bandipur, Brahmagiri and Nagarhole national parks, had gathered around the pit and were bellowing their assurances to the calf. Pamela describes the next hour as magical, as the enormously graceful creatures banded as one to lift the half-broken lid of the pit with their trunks, enabling the little one to clamber out.

This show of concerned unity is typical of the environment the Malhotras have cultivated in Sai Sanctuary, which is nestled within southern India’s Western Ghats in the Coorg district. “Protecting what is left of the world’s forests is the only thing that will ensure our own survival,” Pamela says. “Forests are directly responsible for rainfall, our primary source of water. Water, in turn, is the lifeline for plants, flowers, animals, birds and humans. We have nothing if not for our forests.”

It seems simple enough logic. Terms such as global warming, species extinction, soil pollution and climate change are now part of our daily discourse, dismissed as easily as they are brought up. We know the problem exists, but often, on a personal level, we don’t think that there’s much we can do about it. Pamela demands to differ. “Reforestation is nothing but large-scale gardening. When we bought our first parcel of land in India, it was just the two of us and 55 acres [22 hectares] of forest beside the Poddani River. We learnt from experience that if you want to protect a piece of land, you need to secure both sides of its water source. And here we both are 25 years later, managing 300 acres [121 hectares] on both sides of the river.”

See more: Take a virtual safari through the Sai Sanctuary private forest – in pictures

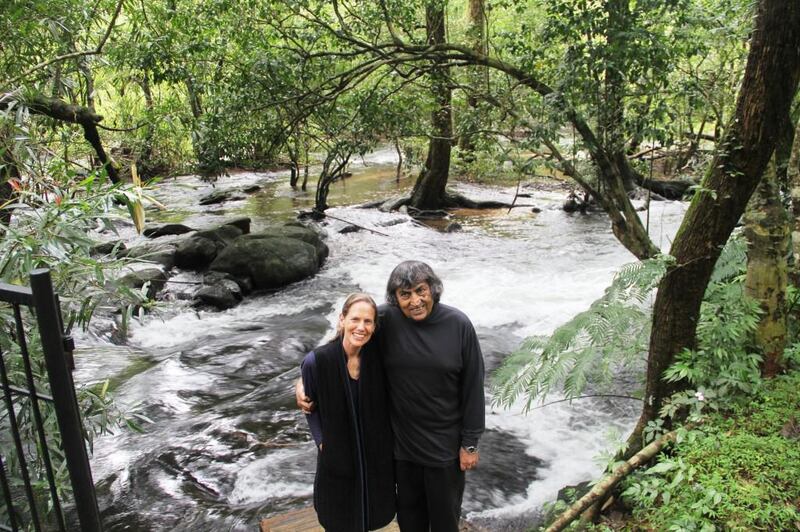

Pamela, who is part Native American, and her husband, a former banker who shuttled between Mumbai and New Jersey, where they met, lived near the Himalayas for 10 years before buying the nearly abandoned Sai Sanctuary in 1991. They follow a two-pronged approach to safeguard the forest, river and wildlife: purchase-to-protect and payment for environmental services. The first step is to buy private forested lands that border national parks or other reserve forests, and preserve them in their natural state. Next, the Malhotras offer compensation to members of the surrounding communities to, in turn, not harm the trees and animals around them. Compensation may be in the form of money, but it can also be a solution that works for both parties.

“We gifted all our cattle to some of our neighbours. The milk and dung give them an extra source of income, while for us it means less staff and more food for other grass-eaters,” says Pamela. “Another time, some villagers approached my husband to help relocate a temple from the top of the mountain to the edge of the sanctuary. He agreed, on the condition that they would stop hunting, even equating monkeys and elephants to the Indian deities of Hanuman and Ganesha to add a bit of spirituality to level with them.”

Ingenious solutions and noble intentions aside, it’s undeniable that money – and large sums at that – is needed for a project of this magnitude. Pamela says that every last paisa from her husband’s inheritance and from the sale of their previous successful venture – a forest reserve in Hawaii, near the Akaka and Kahuna waterfalls – went towards buying the land in Coorg. “We also pay 99.8 per cent ourselves towards the running costs,” she laughs. “However, we now have four rooms in two eco-tourism cottages on the property alongside the main house in which we live.” These cottages are open to visitors, and cost from 2,950 rupees (Dh162) per person, per night, which includes the stay, three nutritious vegetarian meals and daily treks.

The cottages are part of Sai Sanctuary’s Stay and Help programme. Each cottage houses two enormous rooms with a total of six regular-size beds, en-suite bathrooms and a spiral staircase leading to the flat roof, ideal for yoga and meditation, birdwatching and stargazing. As in the other areas of the property, the cottages run on solar-powered electricity and hot water, with a backup generator for monsoon season.

“We outsource not only our housekeeping and laundry facilities, but also hire willing neighbours to cook the meals, some of which can be eaten in a local house or with the village priest. This ensures the money spreads through the community, and even our guests can get a feel for the culture,” Pamela says.

With their in-depth knowledge of the sanctuary and its safe areas, the Malhotras themselves act as guides for the walking safaris. Despite its size, Sai Sanctuary doesn’t have any safari vehicles. “You are always on foot here. It helps people to slow down and observe the flowers, birds and trees around them; to spot a giant Malabar squirrel; or if they’re lucky, to stroke a bold river otter. This will, hopefully, create a love and desire to protect nature,” Pamela says.

In addition to the 300 species of birds, including the paradise flycatcher, found in the forest’s canopy, Sai Sanctuary is home to civet cats, lesser loris, foxes, leopards, Asian elephants, royal Bengal tigers and various types of monkeys and deer. An organic garden and greenhouse are filled with rows of green and salad vegetables, herbs and fruit trees. “We grow flowering plants such as anthuriums and orchids, along with saplings of native trees such as nandi, avocado and limes for transplanting later,” Pamela says. There are also about 75 species of native rainforest trees.

Anand Osuri, an ecologist working with the Nature Conservation Foundation in India, visited Sai Sanctuary in 2012 to study how human-caused disturbances affect the carbon-storing ability of tropical forests. “Sai Sanctuary was a great place for me to study a wide variety of protected rainforest species and collect samples of leaves and wood,” he says. “Also, on a personal level, after a visit to the sanctuary, one experiences a strongly reassuring feeling that nature is safe and thriving.”

Osuri is one of a number of researchers who have visited the sanctuary. “We have hosted both students and scientists. The place is like a living laboratory, so they get a lot out of it,” Pamela says, adding with her usual frankness: “And we started the cottages because we have reached our economic limit, and we are growing old.”

Up to 16 guests can be accommodated in the two cottages, while larger groups can be put up in neighbouring homes. However, there are no plans to construct more cottages. “This is not a resort,” Pamela says. 'We keep it small because we do not want to burden the ecosystem here. Every person needs water, food and clean linen, so one has to have a limit for it to be true to eco-tourism, otherwise it becomes eco-terrorism.”

Similarly, guests are never taken to the same area twice during the course of their stay because “we want the wildlife to move freely even in the day. This is the purpose of a sanctuary.”

The Malhotras now plan to take in more volunteers – “especially if they are social-media-savvy” – to help out. “The Stay and Help programme usually peaks at the end of the monsoon season, from October,” Pamela says. “And while I hope people visit, it is more important for them to recognise and act on the fact that we cannot replicate our trees, even if this means buying their own forest, like we did.”

pmunyal@thenational.ae