The first circle of hell in Dante’s Inferno is limbo, an eerily calm place, save for the “sighs that kept the air forever trembling”. Limbo is neither hell nor heaven; it is the denial of a resolution to one’s life – a constant state of “grief without torment”.

Dante's Christian vision of limbo is not too far removed from the state in which the Lebanese characters in Hilal Chouman's third novel, Limbo Beirut, find themselves.

It’s 2008 in Beirut and the characters are living through a conflict that seems like it could be a war, although nobody is quite sure, exactly.

The conflict in question is, of course, based on the real-life clashes that took place between warring factions Hizbollah and the Future Movement during May 2008. The street fighting seemed to start and end in a violent flash – at least 11 people died – but it brought home a new reality to many young Lebanese who were just children during the country’s civil war.

In Limbo Beirut, though, the names of political factions and leaders are absent. Political affiliations are not the motivating factors in the lives of the young Beirutis portrayed by Chouman. To some, the conflict is a jolt to their stable worlds – an awakening perhaps or a chance to consider what is deeply wrong or right in their own lives. For others, the conflict is just a passing moment.

“War? This is all no big deal,” says Walid, a young artist. “It’s nothing to get excited about. Everything that can happen has already happened to this country. Everything that can be done was done before.”

Though each of the five stories in Limbo Beirut could stand alone, they instead come to overlap in surprising ways. There is Walid, whose jaded nature keeps him at a distance from the world around him. When the fighting starts, he imagines the old men in his neighbourhood to be “very happy”, nostalgic even, at the sights and sounds of war.

Old memories also surface for Walid. He remembers his father having him pose atop the rubble in the downtown city as a child, after the civil war, and that Beirut, “with its hummocks of dirt and its debris and its desolation... resembled hair, thick and dishevelled”.

Like Walid, the unnamed writer featured in the next chapter is more devoted to his craft than the world and people around him, including his Japanese wife. He withdraws from his surroundings to complete his novel and is barely moved when he discovers his wife has left him and returned to Japan.

As he drives aimlessly around the city one night at the height of the conflict, a random decision on his part brings together the characters in Limbo Beirut.

The novel exemplifies how this current generation of Lebanese authors and artists, raised during the tail end of the country’s civil war and the beginnings of an ongoing reconstruction, have been able to interpret more recent conflicts. These accounts are full of inchoate memories of the last war, and disillusion with any future wars.

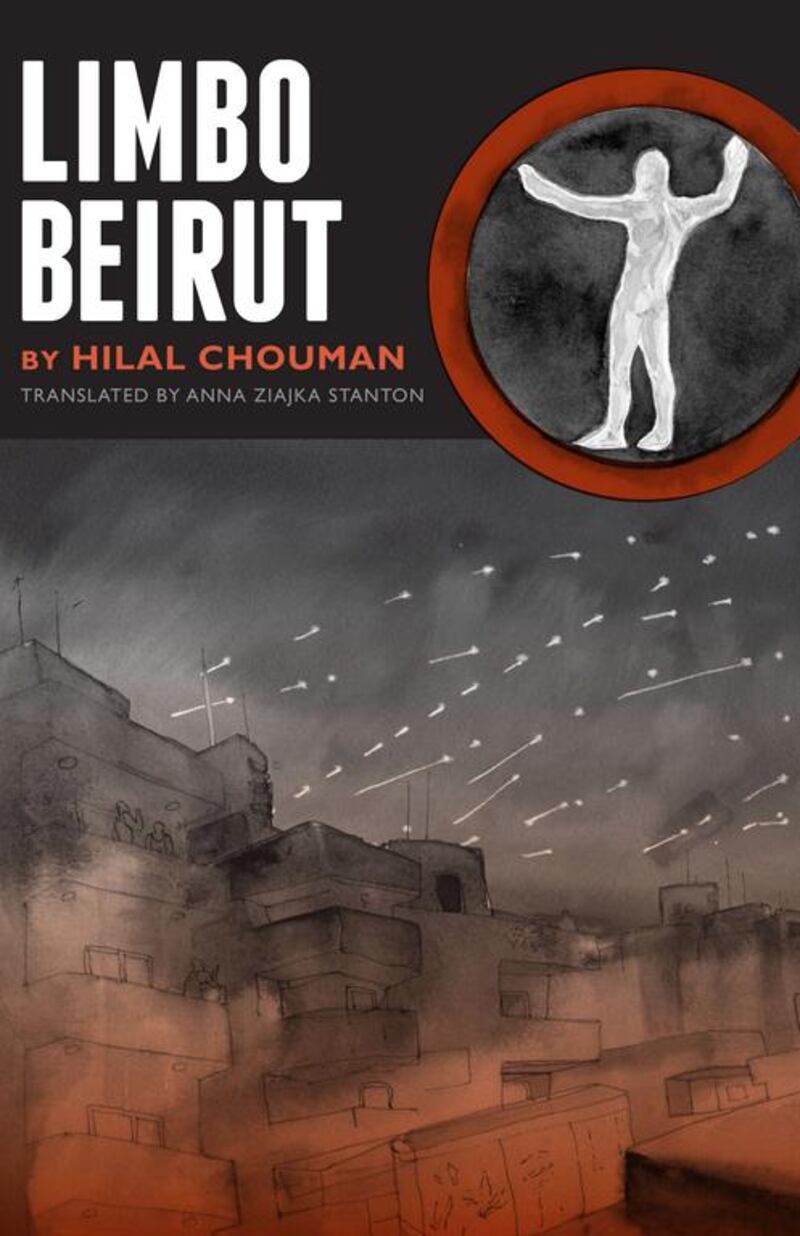

The cryptic black and white illustrations that punctuate the stories in Limbo Beirut – each by a different artist – add to the sensation that the characters are stuck, trying to move forward but unable to. The drawings were specifically commissioned for the novel, which was first published in Arabic in 2013. It is now available in English, translated by Anna Ziajka Stanton, who has attended carefully to Chouman’s poetic expressions of isolation and detachment.

Leah Caldwell writes for Alef Magazine, the Los Angeles Review of Books and the Texas Observer.